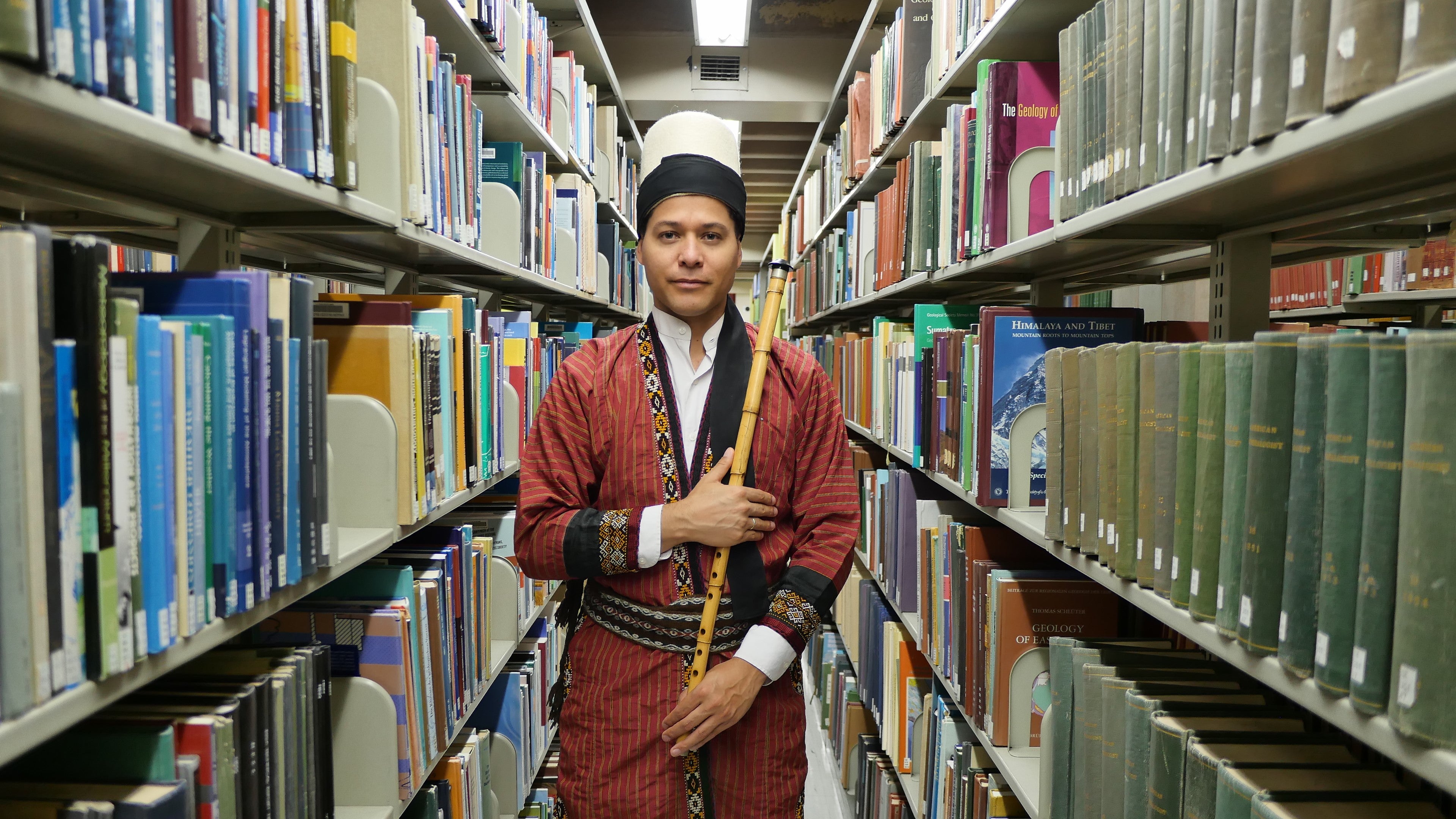

Student Spotlight: Juan Castrillón, Neyzen

The ney flute’s airy, organic melodies are a characteristic element of Turkish classical music, though the melodies don’t come easily. This end-blown woodwind instrument, crafted from a single reed, is notoriously difficult to master, requiring weeks of consistent practice for a novice to produce one recognizable note.

Juan Castrillón is a fifth-year doctoral student in Ethnomusicology at the University of Pennsylvania whose work on mysticism has focused on Turkish Sufism, and especially on the ney. Castrillón — an accomplished neyzen (ney player) himself — will be offering a concert in the Otto E. Albrecht Music Library on December 3, where he will be accompanied by Sufi dancer Ibrahim Miari.

The concert anticipates a forthcoming exhibit of four ney instruments from the Penn Museum. In the spring, Castrillón will curate the exhibit in collaboration with the Museum’s African Collection and the Music Library.

We recently spoke with Castrillón about his scholarship, musicianship, and pedagogical philosophy.

You’ve conducted ethnomusicological fieldwork with Sufis in Turkey and Tukanoan shamans in Colombia. What initially interested you in the intersection of music and mysticism?

I became interested in the intersection of music and mysticism in 2001, when I was an undergraduate student in anthropology. My first ney teacher, Meryem Kiolla, taught me that the ney finds its performer, rather than the performer choosing the ney. She also taught me that mastering the sound of the ney and performing Sufi liturgical repertoire should be the result of a process in which egotistical desires are trained and transformed into a sincere manifestation of the heart.

After studying with Meryem, I wondered about the historical and anthropological dimensions in which musical pedagogy and asceticism configured one another. This question — and everything Meryem taught me in Latin America — brought me to Istanbul in 2005. Since then, my academic inquiry and relation to the ney have provided fertile ground to interrogate why musical education has abandoned philosophical wandering, and to envision the ethnographic study of sacred music otherwise.

You say that your research explores why “musical education has abandoned philosophical wandering.” Have you gained any insight to date?

My research on musical education has focused on Turkey. I’ve found that some educational and urban reforms in Istanbul during the mid-nineties made it difficult for music teachers demonstrating any speculative or theosophical inclinations to be hired within the new educational system implemented by the Turkish Republic.

Can you say anything about the pieces in your upcoming performance?

My performance will include pieces that were probably common at the end of the nineteenth century to specific venues in Cairo and Istanbul, in which Muslim devotional repertores were regularly performed. These pieces include ilahi hymns, peşrev instrumental suites composed during the beginning of the twentieth century, and some recent compositions and taksim improvisations based on the same genres.

Another feature of the recital will be Ibrahim Miari’s accompanying performance of Sufi dance. Ibrahim and I met at Penn in 2014, and we’ve performed together at different events organized by Penn Middle East Center. Playing with Ibrahim is always an amazing gesture against divisiveness; our performances together create an atmosphere of intimacy, in which sound and motion blur the edges of our geographical identities. [Castrillón grew up in Colombia; Miari — who was born to an Israeli mother and a Palestinian father — grew up in Israel.]

What other instruments do you play? What were the particular challenges of learning to play the ney?

I also play frame drums such as daf, bendir, and kudüm, Condor feathers, and digital audio workstations.

The major challenge of learning to play the ney is the amount of time that personal training with your teacher takes. Ney teachers believe in a slow paced learning process. Another dimension of that challenge — especially for me as a graduate student —is the fact that not everyone can live near their teacher, casually drinking tea and listening to them talk about things that would, over a long period of time, inform and improve performance technique.

Is there anything noteworthy about the neys that you’ll be curating for your upcoming exhibit?

They come from the Penn Museum, and they played a significant role in both the American conception of the music history of the Middle East, as well as the emergence of Turkish musicology after World War II. The first record of the Penn Museum reed flutes appeared in The Music of the Sumerians and Their Immediate Successors, the Babylonians & Assyrians (1937). This organological work was well known in academic circles of the time, and almost all textbooks printed in Turkey about how to perform on the ney mention these particular instruments. However, they’ve never been on display at Penn.

The exhibit takes into account the history of displaying Islamic art in the United States, and it will bring a decolonial perspective to these specific artifacts. Beyond exploring the cultural significance of these artifacts, the exhibit is intended to foster further collaborations between Music graduate students and the archeological and ethnographic collection of the Penn Museum.

How have you drawn on the resources of the Music Library in your doctoral work?

For my dissertation, [Head of the Music Library] Liza Vick put me in contact with libraries in Colombia so that I could work with their Tukanoan language collections. She and the Vitale Media Lab also provided logistical resources for hosting a multimodal display — curated by UCLA’s Anthropology Department — during a scholarship media festival that I directed for CAMRA at the Annenberg School of Communication in March. And the ney exhibit I’m preparing reflects Liza’s encouragement of academic curiosity and creativity.

Juan Castrillón is now a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Annenbeg School for Communication.

Date

November 21, 2019