Book Art: Zoe Leonard Sculpture on Display at Penn's ICA

The University of Pennsylvania-affiliated Institute for Contemporary Art (ICA) has no permanent collection. Instead, the ICA features rolling exhibitions of innovative artists both established and emergent. It was famously the first museum to present a solo Andy Warhol show and has hosted works by a miscellany of high-profile artists, among them Cy Twombly, Agnes Martin, Robert Mapplethorpe, Andres Serrano, Jenny Holzer, Yoshimoto Nara, James Turrell, Sol LeWitt, Phoebe Washburn, and Sun Ra.

Penn Libraries houses a comprehensive collection of ICA catalogs in addition to the physical records of ICA exhibitions, dating from 1963 (the year the ICA was founded) through 2000. “A lot of people access this collection — artists, galleries, museums, students working on projects,” says Donna Brandolisio, the Manuscripts Cataloger who supervised organization of the over-300 boxes of records upon their arrival at the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts (Kislak). “It’s an incredible resource in terms of contemporary art history.”

The Warhol materials are among the most frequently consulted by patrons, and Brandolisio notes that “everyone always wants to see Agnes Martin’s exhibition.” In addition to photographic documentation of each show, the collection contains an assortment of ephemera, including museum correspondence with featured artists. “[Former ICA director] Suzanne Delahanty’s letters demonstrate how gracefully she dealt with difficult artists,” says Brandolisio. “People were writing absolutely crazy things, and you see in her correspondence that she never flinched.”

In addition to showcasing single artists, the ICA has also curated shows featuring linked or affiliated artists. The most recent such installation — on exhibition through December 22 — is arms ache avid aeon: Nancy Brooks Brody / Joy Episalla / Zoe Leonard / Carrie Yamaoka: fierce pussy amplified (Chapter V). (The first four chapters of the exhibition were shown at Beeler Gallery at Columbus College of Art & Design.)

A brief background: fierce pussy, a collective of queer women artists and AIDS activists, formed in New York in the early 90s. According to the group’s website, “fierce pussy projects included wheat pasting posters on the street, renaming New York City streets after prominent lesbian heroines, re-designing the restroom at the LGBT community center, printing and distributing stickers and t-shirts, a greeting card campaign, a video PSA and more recently, various installations and exhibitions in galleries and museums.”

The multipart arms ache avid aeon exhibition deviates from the collectivist orientation of fierce pussy’s oeuvre by emphasizing the individual practices of each core member. The artists themselves selected what to exhibit and when, displaying archival work alongside premiere pieces in arrangements unique to each chapter.

One of the new pieces featured in chapter V is Zoe Leonard’s The Picture Universe, a sculpture comprised of a stack of 27 copies of the photography anthology The Picture Universe: 25th Anniversary U.S. Camera (1960). Though the piece previously appeared elsewhere in a slightly different iteration, “Zoe felt that the work did not have the right presence, so she kept buying copies and then determined the size of the work here at the ICA,” says Anthony Elms, Daniel and Brett Sundheim Chief Curator. “She considers this variation a different, new piece.”

Throughout her decades-long career, Leonard has worked primarily in sculpture and photography, and The Picture Universe — a sculpture constructed of photography books — neatly fuses the artist’s two predominant modes. The piece also represents the artist’s proclivity for what Russian formalists termed “defamiliarization,” i.e., the representation of a familiar object in such a way as to render it novel. Leonard’s The Picture Universe, a stack of books that can’t be touched or opened, draws attention to the book as a physical object divorced from its utility.

The artist’s chosen medium has rich historical precedent. “Books have long been treated as material objects, with a life distinct from the content they contain,” says Lynne Farrington, Senior Curator of Special Collections in Kislak. For example, book collectors in past centuries sometimes replaced intact spines of old books with new ones that better “matched,” visually, the rest of their private library. Farrington cites the artist Werner Pfeiffer as a more recent example: “Pfeiffer creates book-objects, taking pre-existing books and reworking them to create sculptures which examine the place of books in the contemporary world.”

Leonard collected the books for her sculpture via both online secondhand retailers and brick-and-mortar thrift stores. According to Elms — who previously worked with Leonard at the 2014 Whitney Biennial, when she was awarded the Bucksbaum Award — there’s no special significance to there being 27 copies of the book other than that number satisfying Leonard’s spatial vision for the piece.

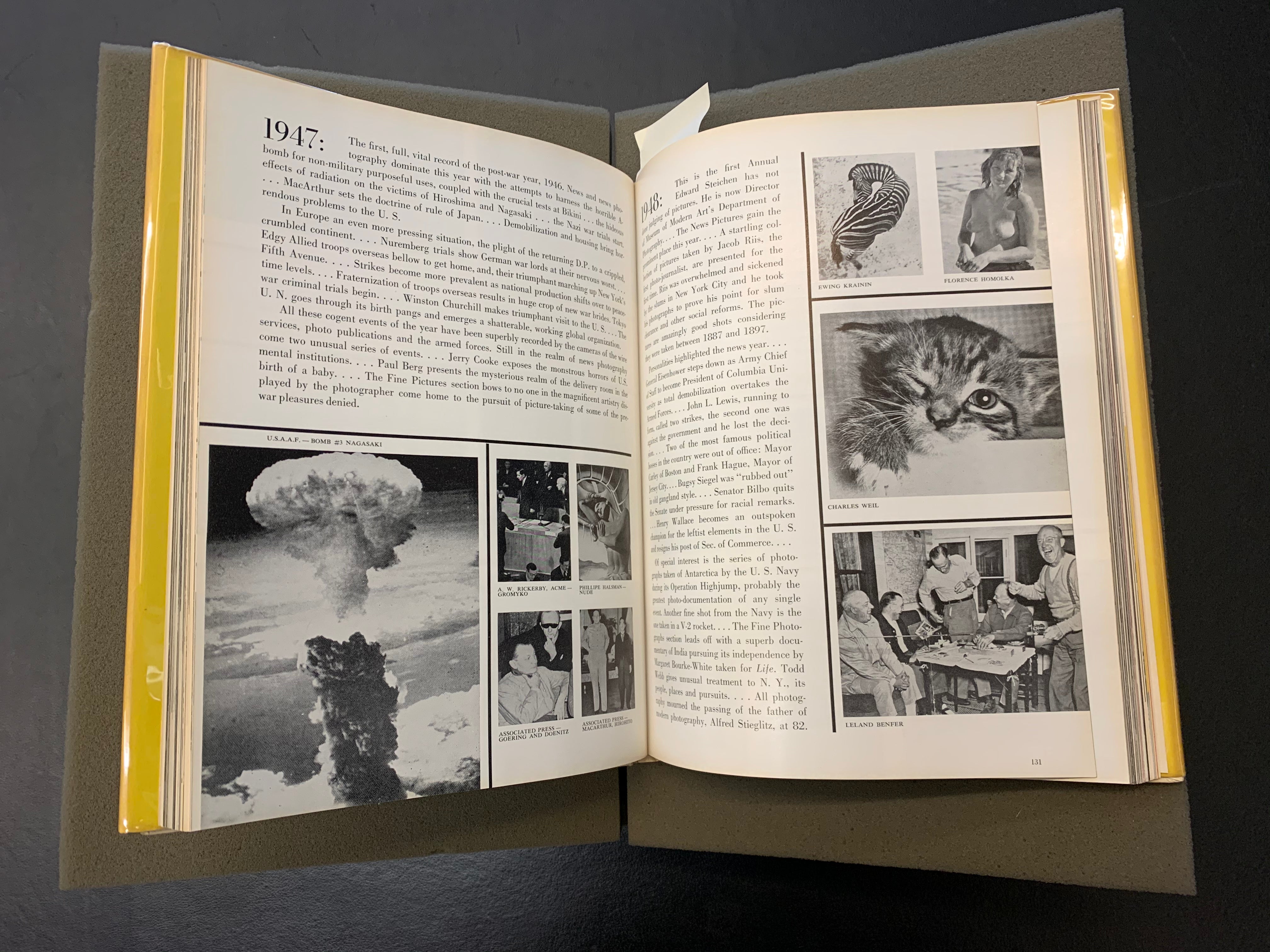

Penn’s own copy of The Picture Universe: 25th Anniversary U.S. Camera currently lives at its LIBRA storage facility but is readily requestable for viewing in the sixth-floor reading room of Kislak. Published by the photography magazine U.S. Camera (1938-69), the book touts itself as “an important presentation of photographic excellence featuring the best work of photographers from all over the Universe.”

The book represents a cross-section of Western history, featuring subjects from Dust Bowl-era migrant farmers to Nikolai Khrushchev, as well as a primer on mid-twentieth-century photographic trends and technology (e.g. the Honeywell Futuramic II strobonar electronic flash, “the most exciting flash unit ever made!”). The image captions are likewise revealing of historical vogue: “Fashion is airborne. The silhouette is shaped by a fresh spring wind — it blows, it flows, it floats, animated by every breath of air. The camera, a Hasselblad,” reads the description of one Gleb Derujinsky photo.

The featured photographers in The Picture Universe: 25th Anniversary U.S. Camera are predominantly white, Western, and male. A significant portion of the photographs are of nude women, thus proving out the art critic John Berger's famous argument that, in Western art, men look while women are looked at. Leonard’s choice of this book then raises the question of canon: who, historically, has determined what constitutes “photographic excellence,” and how does that legacy bear on contemporary art? What does it mean for a stack of books that perpetuate that legacy to be out of circulation and unbrowsable?

Both the former and current versions of The Picture Universe “are peculiar,” says Elms, “quite literally, remnants or revenants. The sculptures fix another photography that we have forgotten and that is increasingly difficult to access or comprehend, yet they do so not by absence but through presence—their existence as forgotten and pretty much past-tense information.”

In contrast, Penn Libraries’ ICA records are, by Brandolisio’s estimation, “still cutting edge. The ICA has featured an unbelievable number of truly groundbreaking artists.” And while Leonard’s sculpture is unbrowsable, Brandolisio implores researchers to take advantage of the artifacts that comprise the ICA records. “There’s a big difference between just reading about an artist’s work online or in a book versus seeing the physical envelope they doodled on,” she says. “There’s always something to be excited about in this collection.”

Date

December 10, 2019