Diversity in the Stacks: North African Books in French

Diversity in the Stacks aims to build library collections that represent and reflect the University’s diverse population.

Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia are located in North Africa, along the southern shore of the Mediterranean Sea. They are commonly grouped within the Middle East North Africa (MENA) region, emphasizing the region’s Muslim faith and Arabic language and culture. Yet, in some ways, these three countries, also called the “Maghreb,” do not fit so easily into this mold. An important feature of their shared history is inclusion as part of France’s 19th and 20th century colonial empire. Morocco and Tunisia became independent in 1956, followed by Algeria in 1962, after a prolonged armed conflict. More than 60 years later, the French language continues to play a role in culture, education, and government.

However, this role is contested and complex. Additionally, though French and Arabic are the most commonly spoken languages, some populations within Algeria and Morocco, particularly those who identify as Amazight (sometimes called Berber), may also speak Tamazight. Who speaks what language often depends on fault lines of social class, the rural/urban divide, and nationalist or Islamist political activity. Thus, a full picture of North African history and culture must take into account this multilingual reality.

Collecting to support teaching and research can present a challenge, as materials in French and in Arabic are often artificially separated. This is due to a variety of factors, ranging from political to technical to ideological. Often this means that French-language literature is read in French departments, Arabophone literature might be studied in Arabic departments, and very few attempts are made to look at the two side-by-side.

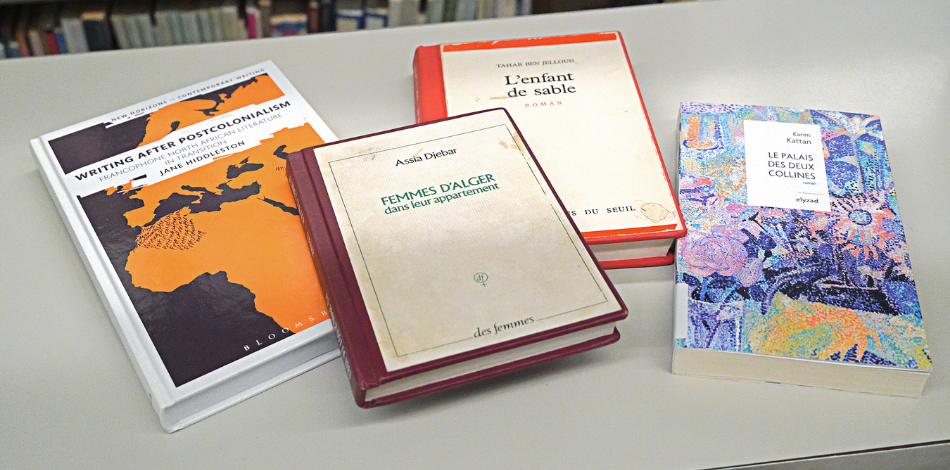

Additionally, some of the most famous North African writers, such as the Algerian Assia Djebar, or the Moroccan Tahar Ben Jelloun, chose to live and work in France, with their books published by Parisian firms. In some ways this perpetuates the divide between French and Arabic and can even prevent their work from being read within North Africa.

In a special 2020 issue of the Journal of the African Literature Association focusing on North Africa (available online to Penn users), Karima Bentoumi reviews some of the factors that complicate publishing in Algeria, ranging from political strife to shortages of materials. Further, she explains that the reading public in Algeria, as well as more broadly in North Africa, can be limited, and cautions against interpreting sales as reflecting popularity or critical acclaim. In Library and Information Science in the Middle East and North Africa (available online to Penn users), Christof Galli explains how low purchasing power and piracy also contribute to low sales in Arab countries.

Yet while books may sell a limited number of copies, they still find an international audience. This is true both within North Africa and among a wider global Francophone public. The International Organization of la Francophonie (OIF) provides a forum for exchange among people in countries where French is spoken, or who wish to align themselves with the organization’s values. Although the OIF has been criticized as perpetuating a neo-colonial influence among France’s former colonies, it nevertheless has a significant cultural presence. Using shared language as an element of cooperation is evident in the yearly program “Dis-moi dix mots” (“Tell me ten words,” link in French), which aims to enhance social ties through creative interpretation of current terms. The Moroccan author Oumelghait Belkziz Boubga uses the selected words as prompts in her novels exploring women’s lives in different settings.

Additionally, since its creation in 2001, the OIF has awarded an annual literary prize, the Prix des Cinq Continents. The most recent recipient, Karim Kattan, who is Palestinian and teaches in France, won for his novel Le palais des deux collines, which was published in Tunisia.

In a sense, the OIF moves the center of the Francophone world away from Paris. Rather than being part of the periphery, other countries around the globe can position themselves as creative, artistic, and innovative destinations. Writing in the Annual Review of Anthropology (available online to Penn users), Cécile Vigouroux explains how a multipolar francophone cultural landscape echoes the post-war vision shared by presidents Léopold Sédar Senghor of Senegal, Habib Bourguiba of Tunisia, and Hamani Diori of Niger. Despite choosing political independence and refusing President Charles DeGaulle’s Communauté française, these leaders saw the French language as a force for culture and education and were instrumental in creating the OIF’s more egalitarian ethos. At the Penn Libraries, including representative Francophone works published in North Africa as part of the collection is an important part of representing the complex linguistic reality of the population.

In addition to the novels mentioned above, the Libraries also acquires French-language works on politics, Islam, art, and culture. Their publication in French reflects transnational networks of scholarly communication. Since the early 20th century, North Africans often went to France or other European countries for university studies and then remained to teach or perform research, which has led to a “brain drain” in their countries of origin. Beginning with the Barcelona Process in 1995 and continuing with the establishment of the Union for the Mediterranean, members of the European Union and partners in North Africa and the Middle East sought to combat this trend by establishing cooperation for security, prosperity, and cultural and educational exchange. An example of a collaborative project is Me3marouNA : Le patrimoine architectural en Tunisie, a venture with the Goethe Institut, bringing together German and Tunisian scholars to examine three sites in the north-west of the country containing vestiges from Antiquity, Roman, and Byzantine eras, as well as from the early Arab conquest. Such initiatives provide greater reach and more opportunities for scholars in North Africa.

Since independence, a succession of local and global events have made their mark on North African literary and scholarly publishing. While ever shifting, like the waves that border one coast and the Saharan dunes that define the other, the position of the Maghreb region at the confluence of multiple influences continues to shape its multifaceted identity. Collecting French-language works sheds light on one piece of this puzzle.

Interested readers looking for a more in-depth and comprehensive view of North African francophone literature can consult:

Littératures maghrébines au coeur de la francophonie littéraire edited by Najib Redouane and Yvette Bénayoun-Szmidt

Writing After Postcolonialism: Francophone North African Literature in Transition by Jane Hiddleston

The Transcontinental Maghreb: Francophone Literature across the Mediterranean by Edwige Tamalet Talbayev

Special thanks to Middle East Studies Librarian Heather Hughes for information on collection development.

Date

May 18, 2022