From a Barn on Cape Cod to the Penn Libraries: An Interview with Stephan Loewentheil on the Path of a Special Collection

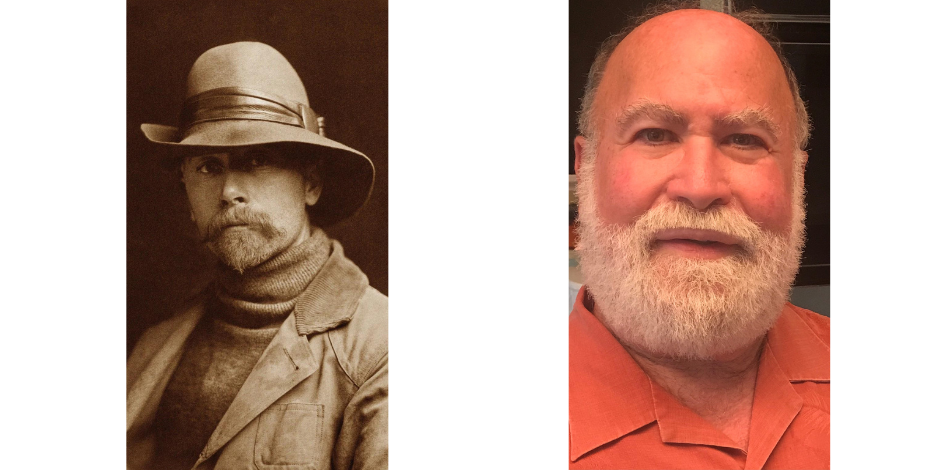

Stephan Loewentheil is an expert matchmaker, but not in the usual sense of the word. The antiquarian, founder and president of the 19th Century Rare Book and Photograph Shop, and member of the University of Pennsylvania Libraries Board of Advisors connects people and institutions to culturally significant books, manuscripts, and photographs. From U.S. presidents searching for meaningful gifts for world leaders to museums and universities crafting exhibitions, Loewentheil’s expertise has played a crucial behind-the-scenes role.

Recently, Loewentheil bestowed a collection of 17 photographic plates by photographer Edward S. Curtis (1868–1952), as well as the related proof sheets, manuscripts, and ephemera, on the Penn Libraries. Valued at $765,750, the collection complements an earlier gift of photographic plates by Curtis from collector William H. Miller III — a client of Loewentheil’s, who made the gift with his guidance — and further cements Penn’s position as a leading center for research and work on Curtis.

The Penn Libraries recently had the opportunity to talk with Loewentheil about his intention behind the gift, the importance of Curtis’ work, and his process for creating artistically and historically significant collections.

What is the background of the Curtis plate collection you donated? When and how did you acquire the plates, and what was your interest in them at the time?

I first encountered the Curtis interpositive glass plates in 2007 at a large photographic auction including a small number of the plates. Having learned that the plates existed, I was then able to track down that owner’s original source. They were in a barn on Cape Cod, owned by the same family who had essentially bought them from the company that produced the plates in the 1920s. I arranged to purchase the entire collection to preserve them for posterity.

My interest in the plates was, and is, both intellectual and artistic. Interpositive plates like these are sharper and more detailed than any other photograph. Thus, many of the plates are important for their sheer beauty and ability to demonstrate the intent of the photographer. Others have markings and edits, so they illuminate the process followed by Curtis in producing the images. The overall collection thus represents both the photographer’s artistic and historic dreams of preserving this subject matter for posterity. I take great pride in being a small link in the chain that has preserved this important evidence and art.

In your career as an antiquarian, how frequently do you come across photographic plates? How do they contribute to the history of photography?

I come across photographic plates like these very rarely. Large format glass plates, or mammoth plates, are infrequently encountered for a number of reasons. They are, of course, old and fragile, and require delicate handling. Glass plates were also expensive, so many 19th century photographers reused them at the time. These plates essentially went out of use around the turn of the 20th century, and because they were not generally recognized as having artistic value, there was not much impetus to preserve them, thus neither collectors nor institutions visualized the significance of these plates until the study and appreciation of photography matured in the mid-20th century. In my years of collecting I have found only a few glass plates by significant photographers, but this was an exceedingly rare opportunity where I found a large number of these rare plates in one location, available for purchase. It was immediately clear to me that by obtaining this large survival, it would be possible in time to preserve this little-known aspect of Curtis’ great work for posterity.

These plates exemplify the period in photography’s history when one had to compose and produce pictures extremely carefully. Due to the tedious photographic process, and the skill and expense required, each exposure mattered. Today, we can take several pictures on our iPhones and figure that one of them will turn out well; at Curtis’ time, each photograph had to be made painstakingly. In the photogravure process that Curtis used, these interpositive plates marked only one step in the transformation of an initial exposure into a final printed image. So these plates illuminate a moment in the medium’s history in which photographers had to go through a very tedious process and use high levels of craftsmanship to create an image. This can be difficult to conceive of in our age of ubiquitous and instantaneous photography.

You have spoken in interviews about the importance of matching a gift of a book or rare artifact with the perfect recipient, as you helped several past U.S. presidents to do. How and why did you select the Penn Libraries to receive the generous gift of photographic plates, as well as match the Libraries with Mr. Miller and his gift?

My colleague Constantia Constantinou, the Vice Provost and Director of Libraries at Penn, had asked me to join with her and the Board of Advisors to provide assistance for the growth of the spectacular special collections at the University of Pennsylvania.

Plus, I had been looking for a special gift for the Penn Libraries to commemorate my association with Constantia and Penn. Because of the Libraries’ unique relationship with the Penn Museum, I was interested in finding a gift that could be of use to both institutions. I believe that the significance of historical imagery in the process of education and scholarship gives these Curtis plates significant academic and artistic value. Not only do these plates document Native American cultures at a specific moment in history, but they also hold great aesthetic interest. Furthermore, the plates are situated in a complex conversation about representation of Native American cultures, as we evaluate Curtis’ decisions in framing and editing these images. I felt that, given their interdisciplinary interest, these plates would be useful for exhibition and study across both institutions.

Mr. Miller was a long-time client of mine. He wanted his gift of photographic plates to go to an institution where they would be of value and best fit in with existing collections. I believed the plates could be of interest to both Penn Museum and Libraries, as well as a complement to the Kislak Center’s collection of historically significant photographs. Because of Penn’s existing collections and the interdisciplinary possibilities of its many cultural and academic institutions, I believed the Penn Libraries were a perfect match for Mr. Miller’s gift.

How do you think your collecting experience influences your perspective as a member of the Penn Libraries’ board of directors?

I have been a collector and a dealer of important intellectual and artistic works throughout my entire life, during which time I’ve worked with major libraries, institutions, and collectors.

My scope and depth of experience developed over 40 years in this field have given me a keen perspective on what is significant. This includes an appreciation for an item’s intellectual importance and its appropriateness for a particular collection, as well as its rarity and value. As a member of Penn Libraries’ board of advisors, I believe I can be of significant assistance in helping Constantia and her excellent staff evaluate opportunities for developing collections in current areas of expertise and exploring new areas of interest.

What do you see as the role of collections for an academic library, and Penn Libraries in particular, in the 21st century?

I believe that the modern student, and educator, is increasingly conditioned to obtain information visually. Today, the use of computers, screens, and imagery is one of the primary modes of information circulation around the world. As the academic library evolves in the 21st century, I therefore believe it is increasingly important to build the reservoir of images to maintain Penn’s position as a leading research institution in the face of growing changes in information technology.

Part of my role in that development is to help important institutional libraries recognize the need to focus on this imagery from earlier times – bridging our digital, image-saturated age and the time when photography was first perfected and used as a mode of transmitting knowledge.

As we move forward in history, it is the duty of great institutions to continue the longstanding collecting traditions, while evolving to remain accessible to current and future students. Through these collections, we can use objects to help tie the past to the future.

Do you have a favorite item, or one that you find most interesting, within the collection you donated – and can you share a bit about it if so?

The part of the collection that interests me most is actually not a plate, but a set of printed photographs bearing various editorial markings and corrections. In a set of 23 proof sheets from The North American Indian, you can see how Curtis’ photographs were to be cropped and edited for use before publication. I have not seen anything else quite like these sheets, so they are fascinating in their rarity alone. However, what’s particularly interesting is the insight they provide into the process of creating a perfect image. These annotated sheets show that as much as these photographs are faithful recordings of life, they are also images that were deliberately framed, edited, and contextualized by Curtis and his publishers.

Date

March 31, 2022