"Just Make the Data Available": Exploring Manuscripts with OPenn

It’s National Library Week! Along with institutions across the country, we’re celebrating the wide variety of ways that “libraries extend far beyond the four walls of a building.” Follow Penn Libraries on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram to learn more.

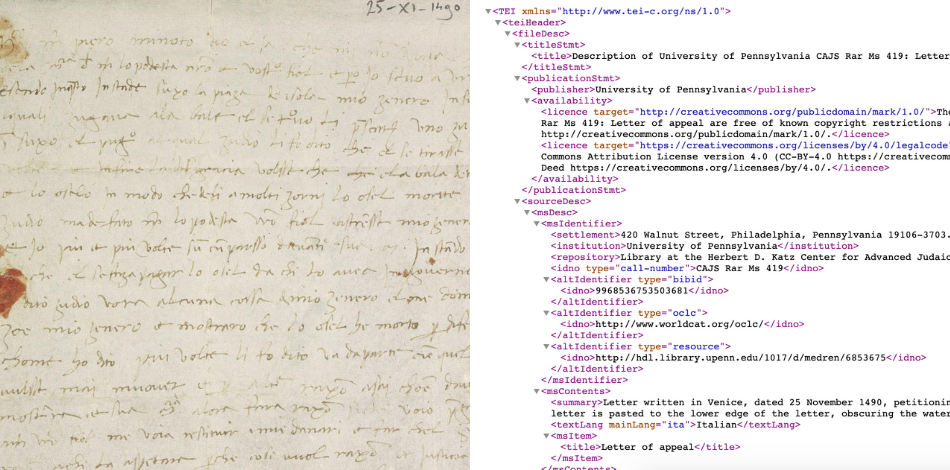

Once upon a time, examining pages from one of the Medieval manuscripts held by Penn Libraries’ Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts would always require someone to make an appointment with a curator, travel to Philadelphia, and visit the Charles K. MacDonald Reading Room. While the experience of viewing a rare book or manuscript in person is still one of vital importance to researchers, this is not a trip that just anyone had the capability to make, even before the COVID-19 pandemic restricted all our movements. Since the late 1990s, Penn Libraries has helped researchers surmount this obstacle through a wide variety of digitization efforts, including projects like Penn in Hand and Print at Penn. Today, one way to explore the Libraries’ digitized manuscripts is using OPenn, a website hosting high-resolution archival images of manuscripts and descriptive information about each one of them. Launched in 2015, OPenn now holds just over 10,000 documents and more than 1 million individual images from over fifty institutions, including the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, Columbia University, the Rosenbach, and the British Library, all freely available to download, use, and share.

Making library materials accessible to as many people as possible has long been central to how librarians conceptualize their work. The availability of technology that allows us to take high-quality images of collections items and share those images in a multitude of ways online has opened up a new universe of possibility. Today, people share and study library collections in ways that are increasingly complex. In response, the Penn Libraries has made it a strategic priority to expand and streamline access to the resources our users need to create, disseminate, and preserve knowledge--including through digitization.

But digitizing collections is not as simple as snapping a photo of a cool book and sticking it on the internet. Digital library professionals must consider the cost of equipment that can produce high-quality scans, the fragility of the objects they want to digitize, and the long-term plans for storage of resulting image files, which are often enormous. They also must invest in creating metadata--detailed descriptions of digitized items that help people find what they are looking for and tell them important information about it that they could not be glean just by looking at it.

Staff at the Penn Libraries kept these considerations in mind when launching OPenn. The project was inspired by a similar effort at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland to digitize and make accessible a 10th century manuscript called the Archimedes Palimpsest. Doug Emery, the Special Collections Digital Content Programmer and head of the Cultural Heritage Computing group in the Libraries’ Technology & Digital Initiatives division, had been part of the effort at the Walters. The decisions made during the course of that project went on to directly inform OPenn.

“When we first started talking, I thought, well, we’ll build an application that will make it so you can browse through the data,” explains Emery. Data, in this instance, refers to the images themselves, as well as the descriptive and structural information about the manuscript pages--the metadata. Many digital collections repositories take the approach Emery first considered, including Penn’s own Colenda Digital Repository. But at the Walters, they ended up going in a different direction. “We decided to just make the data available.”

When Emery and Dot Porter, now the Libraries curator of digital research services, came to the Penn Libraries, they decided to replicate what had been done with the Walters, beginning with materials from the Lawrence J. Schoenberg Collection of Manuscripts. Thus, OPenn was born. They focused their resources on creating something that gave anyone access to the highest-quality images possible, a trove of associated information, and the ability to download and manipulate both the images and the metadata. The quality of the images allows users to view minute details they might otherwise miss, and the high level of detail in the metadata encourages them to look at the manuscripts in a new light. In the years since, the manuscripts on the website have grown in scope to include those from other parts of the Penn Libraries’ collections, as well as materials from other institutions.

Though anyone who is interested in looking at fantastic images of historical documents can browse or keyword-search the OPenn website, it is built primarily for researchers and digital humanists with some programming knowledge. With this in mind, people can download all the data and metadata associated with a manuscript in a variety of formats. The metadata is remarkably broad--it includes not just basic information like the author of the manuscript and the date it was published, but also details about the author’s handwriting, the manuscript’s use of symbols and decorations, the way the manuscript was originally structured, the history of its ownership, and more.

How might someone use this information? Dot Porter has turned a number of manuscripts into ebooks that a person can virtually flip through. You can also explore the manuscripts using the website she created for a 2016 project called Bibliotheca Philadelphiensis, which was specifically dedicated to digitizing Medieval manuscripts held by institutions in the Philadelphia region. BiblioPhilly, as it’s commonly called, takes OPenn’s metadata and lets you sort and search manuscripts in a way more conducive to finding something specific. For example, you can use the BiblioPhilly search for all of the project’s manuscripts created in Spain in the 14th century that include illustrations.

Porter is very excited by the creative and intellectual opportunities offered by OPenn’s data. For example, in recent years scholars from across the world have embarked on a number of different projects to trace the movement of manuscripts over time. OPenn’s detailed metadata would lend itself well to a similar project. She would also love to see people “play” with the images and information. “Because the data is out there and the images are all out there, someone could create their own ‘My Ideal Manuscript,’ which could be bits and pieces of lots of things. That would be really fun.” With a little creativity and some programming know-how, you could create, for example, an alternate history where 18th century physician Benjamin Rush corresponded with the ancient Roman thinker Hippocrates or a comic book featuring illustrations of birds from illuminated manuscripts.

Along with serving researchers, OPenn seeks to serve the library and archive community. As noted earlier, digitization efforts are costly and time-consuming, and OPenn has been a boon to a number of institutions who lack the capacity to embark on such efforts on their own, or even just lack the server space to store large amounts of data. “We wanted to extend the idea so that we could collaborate with other institutions and really spread the advantage of OPenn to anyone who wanted to collaborate with us,” says Emery. “It’s particularly useful and important for those institutions that don’t really have the ability to host their own data online.” This cross-institutional collaboration further helps researchers because they can peruse thematically-connected manuscripts that live in a number of small, separate repositories--for example, the churches and synagogues of Philadelphia. “[Researchers] don’t have to go traipsing around to every congregation,” says project cataloger Kelly Tuttle. “The collecting and the making available has already been done by somebody else.”

Tuttle came to Penn as part of a project to digitize manuscripts associated with the Muslim world Noting that many institutions, for a variety of reasons, require researchers and other interested users to get official permission to use digitized materials, Tuttle says, “OPenn is just so nice because all the data's there, you can take it, you can do what you want. I get emails from people asking, ‘Can I have this picture?’ And I say, ‘Yes, it’s on OPenn! You don’t have to ask permission to use it. That’s what makes it so, so good.” Some of the items do have rules about use--for example, most of them ask that users credit the source--but OPenn strives to provide as few barriers as possible.

Digitization project coordinator Jessie Dummer agrees: “If we were a product, our ad campaign would be, ‘You don’t have to ask permission.’ “

Have you found a creative way to use the data made available through OPenn? We want to hear about it! Email openn@pobox.upenn.edu.

Date

April 7, 2021