Penn Libraries Unearths Dissertation of Trailblazing 19th Century Physician M. Alice Bennett

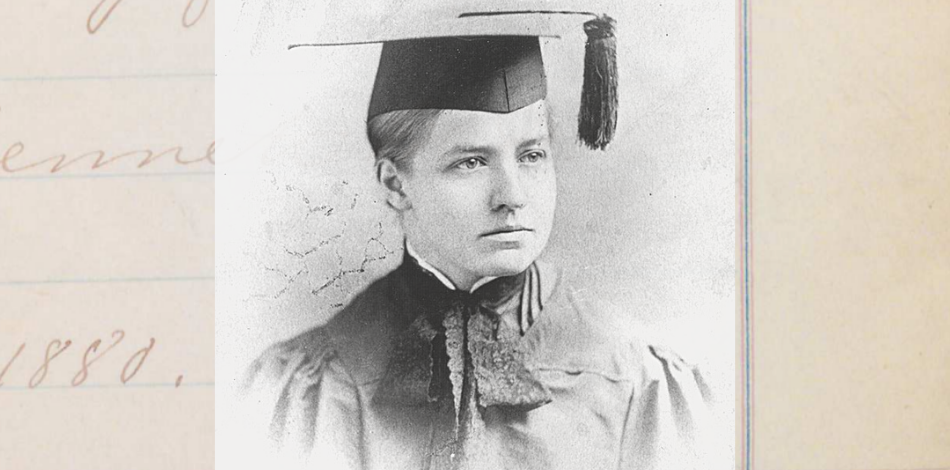

The University of Pennsylvania plays a major role in the preservation and documentation of the history of women in medicine, and the Penn Libraries recently located and digitized a record that tells an important part of this story. The dissertation of M. Alice Bennett, the first woman to receive a degree from Penn, sheds light on her medical interests as a student at Penn’s School of Auxiliary Medicine before she began a trailblazing career in psychiatry and women’s health care.

Eric Dillalogue, Assistant Director of Operations at the Kislak Center, tracked down this historic document after learning about its existence from Dr. Kenneth J. Weiss, the Robert L. Sadoff Clinical Professor of Forensic Psychiatry in the Perelman School of Medicine. Weiss has studied Bennett’s career and work since 2013 and has written numerous papers about her contributions to the field of psychiatry and the treatment of female mental patients.

Although Weiss initiated the search for this document with his own research in mind, he emphasized its value as part of the historical record given Bennett’s significant role as a mental health care pioneer who changed the way patients, particularly women, were treated.

Today Bennett is remembered for her innovations in the humane treatment of people with mental illness. She prohibited the use of restraints like straightjackets and introduced occupational therapy for patients including music, painting, and crafts. According to the University Archives, Bennett argued, “I can have no shadow of doubt that extraordinary precautions often suggest, or increase, the violence they are intended to prevent. Freedom of action is a wonderful tranquilizer.” In honor of these forward-thinking practices, former Penn President Amy Gutmann named the Mary Alice Bennett University Professorship and awarded it for the first time in December 2021.

The way Bennett’s career unfolded is unorthodox by today’s standards. She earned a degree from the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1876 and then enrolled at Penn to study anatomy. She juggled her studies at Penn with two jobs: as a volunteer at a Philadelphia dispensary where she offered health care to poor women, and as an anatomy teacher at the Women’s Medical College.

“She had no demonstrated interest in mental health matters,” Weiss says. “In 1876, when Dr. Bennett graduated from the women’s medical college, she was fully intending ... to teach anatomy."

Bennett would not go on to teach, though. Upon graduation, she was approached by Dr. Hiram Corson of Plymouth Meeting who in addition to practicing medicine was considered an advocate for abolitionism and women in medicine.

“Dr. Corson understood that it might be advantageous in the mental health field for female patients to be treated by female doctors,” Weiss says. Corson began recruiting women into the mental health field and asked Bennett to run the women’s division of a new asylum in Norristown in 1880. Weiss believes she was the first woman in the United States to hold a psychiatric leadership role. Bennett would spend the next 16 years at what was called the State Hospital for the Insane for the South-Eastern District of Pennsylvania, now known as Norristown State Hospital.

While at the asylum, Bennett provided expert testimony in a criminal trial, which Weiss believes was likely another “first.” She applied psychiatry to the law in defense of Sarah Whiteling, who was accused of fatally poisoning her husband and two children in order to collect insurance money. Bennett believed mental illness made Whiteling less culpable and continued to campaign for a commutation of her sentence after she was found guilty, though she was ultimately unsuccessful. Although Bennett was unable to convince the jury, Weiss says her arguments showed that she was ahead of her time in bringing “sensitivity to diversity in psychology.”

While attending a Pittsburgh convention as the president of the Montgomery County Medical Society—she was the first woman in the country to hold such a position--Bennett made another remarkable choice. She learned about the Johnstown flood, in which thousands of people were killed, and decided to act as a psychiatric first responder. “She speculated that there would be mass hysteria and gross psychic trauma to the inhabitants, the survivors, so she rushed over there,” Weiss says. “She contributed by making people aware that individuals who have experienced disasters might be in need of immediate mental health services.”

Bennett’s willingness to try new approaches led her to study several potential contributors to mental illness (which was not categorized into different diagnoses the way it is today), such as kidney disease, heart disease, and ocular conditions. “Dr. Bennett was continuing to try to understand the physiology of insanity, ‘insanity’ being a medical term at that time,” Weiss says. This led her to oversee ovariectomies (the removal of both ovaries, which today is called an oophorectomy) of several patients based on a theory that this procedure would lessen mental illness symptoms for patients. This practice was performed without patient consent and was investigated by a medical review board. Although Bennett was not asked to leave, she apparently resigned from her post at the asylum in response to this scrutiny of her work.

She continued to work in psychiatry, however, and took on a job as the attending psychiatrist for a young lady from a wealthy family who is thought to have had schizophrenia. She held this position for about four years and resigned in 1900, after which there is still a gap in the historic record. Eventually, she moved back to Massachusetts, where she apprenticed herself to a doctor and became an obstetrician. Bennett emerged again in 1910, this time in New York City, where she worked and apparently lived in a downtown hospital. She would deliver more than 2,000 babies before her death in 1925. Weiss said the record shows Bennett delivered babies free of charge, and it is unclear how she supported herself. She never married or had children of her own.

Weiss has been on the hunt for Bennett’s written works for years, and her dissertation – while not directly related to her career in psychiatry – helped fill in another piece of the puzzle.

“This dissertation is fully catalogued and is available in Colenda [the Penn Libraries’ digital repository] for anyone to view,” Eric Dillalogue of the Kislak Center says. Dillalogue’s search was a complex undertaking because the dissertation was part of an archive of records that were catalogued according to the outdated Dewey Decimal system. These materials are slated to be re-catalogued and digitized.

“These early dissertations are all handwritten. In general, people had very good penmanship but … the paper isn’t necessarily the highest quality. Sometimes it’s just difficult to determine the strokes of the pencil or the pen,” Dillalogue says. “It’s difficult, but that’s one of the reasons that we do these high-resolution scans.”

Without Weiss’s outreach, Dillalogue would not have known the significance of Bennett's work. “We would have processed this dissertation and put it on the shelf” without knowing its context. “[Weiss] really gave us a much richer picture of the material.”

Date

March 16, 2022