Shedding Light on History Using Linked Data: An Interview with L.P. Coladangelo, LEADING Fellow

As a Ph.D. candidate at Kent State University’s College of Communication and Information and a recent LEADING fellow with the Penn Libraries’ Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies (SIMS), L.P. Coladangelo thinks a lot about the knowledge organization of cultural heritage.

“Knowledge organization is the way in which we gather together and place in order and context all of the ways we make sense of the world, and often that’s done through words,” he explained. Library subject headings are a type of knowledge organization; so are the biological taxonomies that many of us learned about in high school biology.

The knowledge organization of cultural heritage is a bit less tangible than these straightforward examples, though. Essentially, it’s a matter of examining how people use words in particular cultural contexts to mean very specific things. Coladangelo has done quite a bit of research in this area related to folk dancing.

“Folk dancing has this rich vocabulary of calling traditions, of how the dances are announced. Taken as a list of words, the vocabulary is sort of meaningless. But dancers understand them in context.”

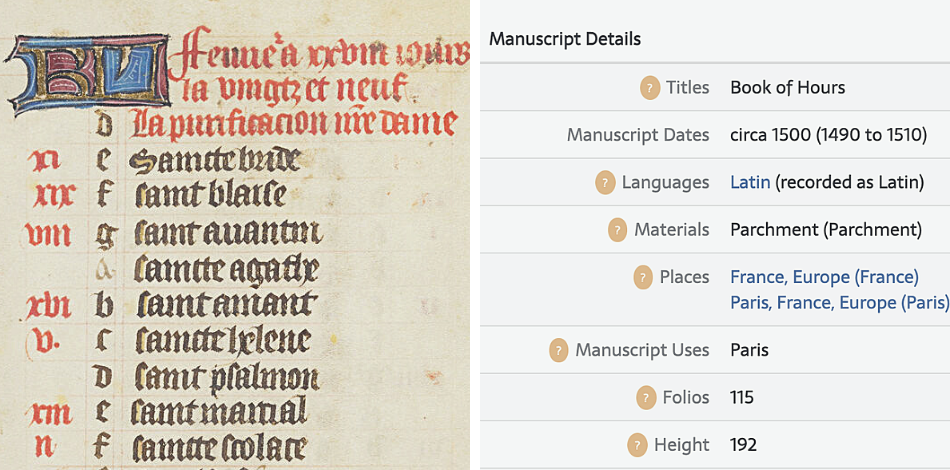

In the fall of 2021, Coladangelo brought his nuanced take on the words people use to convey cultural knowledge, along with his experience working with linked data, to SIMS to help improve the massive Schoenberg Database of Manuscripts. First created by Lawrence Schoenberg, whose 2011 donation established SIMS, the database aggregates information about medieval manuscripts from all over the world. Scholars can use it to find out where a particular copy of a manuscript resides, its size and condition, and some of the people who owned it in the centuries since it was created. They can even add missing information about the manuscripts, document their own personal observations, and converse with other experts. Importantly, the database also has established name and place authority files, which ensure that people and places are listed in a consistent manner. That means that users of the database don’t have to, say, search for multiple spellings of a person’s name to find the information they are looking for.

The Schoenberg database is already incredibly robust, but Coladangelo wondered, what if it could be linked to other datasets of bibliographic information? Would that allow scholars to make new connections—among people, places, and libraries—that had previously been invisible?

Last month, we sat down with him to learn more about his project, what it taught him about communicating across disciplines, and how he hopes his work will help researchers enrich their understanding of the past.

-

What do you find particularly interesting about the Schoenberg database?

It’s not a traditional database. It has some qualities of a traditional bibliographical database, but it also has the crowdsourcing element. It’s really interesting how you take that crowdsourced knowledge, which is another of my areas of interest, and build it into something that then becomes authoritative and useful, and something you can query to do serious research.

It's not just people contributing their knowledge in a forum. It's not like social media. But it’s turning something that has a social component into a rich cultural product.

- Can you describe the work you did with the Schoenberg database for your fellowship?

When I first talked to Lynn [Ransom, Curator of SIMS Programs and Schoenberg Database Manager] about the project, [we started by discussing] ways we could connect the Schoenberg database to other data. Because while the Schoenberg dataset is rich, it’s limited to traditional kinds of authoritative data like names, dates, and places. But there's other things that folks want to understand about these people and corporate bodies listed in the database that just aren't captured in the dataset.

So we asked ourselves, what other rich datasets exist out there? Well, there’s Wikidata.

Wikidata has rich connections and links to other authority files, so where someone is represented in one place—say the Library of Congress, or the Vatican Library, or the German Library database—they’re represented in Wikidata. So we can now, using Wikidata as that hub, connect the names in the Schoenberg database to all those other authority files. And that happens automatically by virtue of how that data model works.

And that’s great from a library perspective—that's the thing that library folks are interested in, connecting that metadata. What becomes useful to manuscript scholars is all the rest of the biographical and cultural information that is listed in Wikidata. So all those social relationships, political relationships, creative relationships [become visible]. We can now query things like gender, which is not represented in the original Schoenberg database. We can query family relationships, we can query what kinds of organizations someone belonged to, or ask, did they espouse a particular religion? You can start to ask more culturally rich questions.

- How can asking these new kinds of queries help manuscript scholars advance their research?

I know that some of the folks that Lynn is working with, they have a particular interest in female manuscript collectors, for instance. How well are they represented in the Schoenberg database? And how well are they represented in the universe of research?

It could be that, except for the Schoenberg database, these collectors don't have a robust digital record, so the information from the Schoenberg database becomes the first point of contact for saying, ‘these people existed, and they existed in this capacity, and here's the evidence we have.’

And then when we add that information to Wikidata, we now have this open digital representation of that person. Then other folks, who may be part of the manuscript community and or may not be, can contribute data about that person, and we can start to flesh out more robust digital representations of people who were otherwise unknown or neglected by the previous record.

I think that's going to be the case especially for traditionally underrepresented or marginalized people when it comes to the manuscript record, like women who were manuscript collectors or involved in the manuscript trade.

Lynn and her colleagues [are also interested in learning about] non-Western people involved in manuscript production, particularly from the Islamic world or the East Asian world. That’s not traditionally what we think of in terms of medieval manuscripts.

But those names are now being given more digital flesh so that more meaningful questions can be answered. And so we can start to broaden that lens of manuscript studies because we have more and more and more digital evidence that's meaningfully linked.

- Are there ways that working with the Schoenberg database has advanced your independent research?

From a practical level, there’s a bag of technical skills that I developed and that I now feel confident about pushing forward and using in the future for linked data and metadata research.

The second portion is related to understanding [how to do this work] in an ecology of people. You have folks with different kinds of mindsets, and with different kinds of backgrounds, and different kinds of skill levels, who all are meaningful partners in digital humanities work. And the nascent teacher in me is really focused on the idea of communicating and explaining what's happening to different folks on their home turf. It's one thing to be able to talk to library folks who have a natural understanding of why we have controlled vocabularies or why metadata schemas are constructed in a particular way. And then you talk to manuscript scholars, and they have no knowledge or very limited knowledge of those kinds of practices. So you have to come to them and say, ‘OK, I understand you may have questions or frustrations about why these things are represented in a particular way, say in Wikidata, but let's think creatively of the ways that we can leverage the data so that you can get the most out of it.’

It really involved understanding that digital humanities research is not just about bringing together an eclectic group of people, and some magic happens. It's really about forming and bridging ideas where different knowledge domains conceptualize these things differently.

That bridge building becomes a lot of fun because you can see the fruits being borne out by just having simple conversations. [They say], ‘Oh yeah, now I understand that if I contribute this to Wikidata that makes it available to everybody, and now folks can link this information with other information. Yes, that's great.’

- What do you hope will happen with your work now that your fellowship is complete?

What I’m excited about is the transition to the crowdsourcing element that's made the Schoenberg database so unique and powerful. We now can say, ‘Hey folks, you've been contributing information to the Schoenberg database, but now if you want to help us out more broadly, you can help us get more names into Wikidata.’

- Anything else you want to share about your experience?

This has been a super rewarding experience for me. I now know so much more about folks involved in the manuscript tradition than I ever thought, and I have also come to understand the deep and underlying issues that exist related to cultural heritage.

It's just really fragile. In a lot of cases, we just have a name recorded in one book, and that's it. That's the evidence that exists for this person in history. So just the idea that even if we take that one data point, if you will, and we disseminate it or replicate it and represent it in multiple datasets, then we’ve kept that one kernel of information alive. Even if someone’s existence is simply documented in just one place, we can now sort of multiply that across the digital record.

To me, that's the coolest part of this kind of work in terms of linked data. We're not making up information about that person. We're just simply saying, this person is represented in this place, and the more datasets we can have that data point in, the more evidence of that person's existence can unfold in the future. That person becomes more than just a name in the marginalia.

Date

February 8, 2022