Digital Natives: How the University of Pennsylvania is Preserving its Born-Digital Collections

As counter-intuitive as it may sound, the oldest items in the Penn Libraries’ collections might be easier to preserve than some of the newest--namely, different kinds of digital files. Though it still takes expertise and careful handling, the protocols for maintaining a 15th century book are well established. In everyday life, paper can be easy to lose while digital documents are only a keyword search away, but when it comes to preserving these items for decades, and maybe even centuries, digital files, which range from emails, to jpegs and gifs, to designs made with specialized software, can be terribly slippery.

That’s why a group of archivists from across the University came together last year to create a strategy for collecting and preserving these difficult but increasingly significant materials. In April, they took a major step in improving the process for all of Penn when they selected Archivematica to be the program used to preserve what librarians and archivists call “born-digital” materials.

To help illustrate the significant dilemma facing archivists who want to add these kinds of materials to their collections, digital preservation librarian Rachel Appel suggests a thought experiment: imagine that you are a celebrated figure in your professional field and you decide to donate your papers to the Penn Libraries. What documents would best chart your career trajectory? They might include papers, physical photos, and books, but they would probably also include Word documents and emails. What about those off-the-cuff thoughts you jotted in a Notes file that eventually led to your greatest achievement? What about the photo you snapped at an important event on your first-generation iPhone and never bothered to import to your computer? In accepting the generous donation of your files, library staff would need to ensure that they had the equipment and expertise--including the correct hardware and software--to access all those different file types and formats in perpetuity.

Paper may grow delicate with time, but it’s significantly more straightforward for an archivist to assess and process. “When you see a CD or something like that, it might have a title on it, but you don't know what's inside until you actually try to play it,” notes Sam Sfirri, processing archivist at the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts, and another member of the born digital team. “You need a computer to act as your eyes to look within that folder. If it's a physical folder with pieces of paper in it, all you have to do is open it.”

The need to create a comprehensive system for preserving born-digital materials became particularly acute in 2019, when the Architectural Archives at the Stuart Weitzman School of Design received the full digital office record of the architectural firm Venturi, Scott Brown, and Associates, the team behind Penn’s Perelman Quadrangle, the 1991 restoration of the Fisher Fine Arts building, and designs for universities, libraries, and museums all over the world. The Architectural Archives had already received more traditional archival materials from the firm, but these new digital materials--which included architectural renderings created using design and CAD drawing software, digital photos, word processing documents, marked-up book drafts, and office emails--posed unique challenges. It fell to Allison Olsen, the archives’ digital archivist to figure out what to do. She reached out to the Biddle Law Library’s Sarah Oswald, who also found herself increasingly handling born-digital materials. By the summer of 2020, Appel and Sfirri had joined the group, and the four began formally investigating how Penn might ensure that the digital materials in their collections would survive the ages.

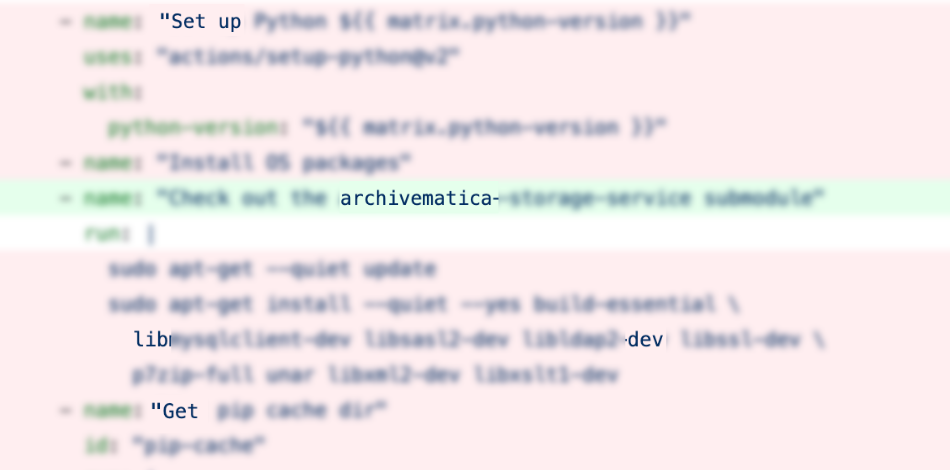

An important step in this process was choosing Archivematica. Created by and for archivists, this suite of open source software allows archivists to add digital items to collections, store those items, and access them. The team particularly appreciated that this program was built according to Open Archival Information System principles, which are increasingly standard for digital preservation systems in archives all over the world.

But as Appel is quick to point out, “Digital preservation is not just software. [Archivematica is] a great cornerstone for our program, but it’s not the solution. It's not like we put it in there and it's over….It requires a lot of that care and feeding.” Some of that care and feeding comes in the form of additional software and hardware. Among other kinds of equipment, the team acquired a Forensic Recovery of Evidence Device, or FRED, which allows them to make copies of a wide variety of digital materials that can then be safely viewed and analyzed without risking damage to the original media files themselves. If you have ever opened up a word processing document on a new computer only to realize that all your formatting has changed, you can understand how this might be an important part of the digital preservation process.

Some of that care and feeding is about building collaboration and community across the University. “Coming together to build a solution was also part of the process,” says Appel. “[One person] can’t do all of this by themselves. It’s nice to have everyone’s support to work together.”

Making decisions together about the hardware and software necessary to preserve digital materials allowed these archivists to make the connections they would need to build processes that would remain in place for years to come.

The team is excited for the opportunity to educate their Penn colleagues about the preservation of born-digital materials. Part of the education process will be to remind users, donors, and fellow archivists and librarians that digital materials can have a long and significant life, as well as teach them best preservation practices for their own digital files.

Many people think of their digital creations as ephemeral, maybe even not quite real. As Sam Sfirri notes, “As much as we think of digital files as not being physical, they really are.” Like traditional materials, digital files decay, they can be lost and destroyed, they bear the marks of the lives they’ve lived.

While paper is never going to go away, managing born-digital materials is also a growing part of every archivist’s job. “This process will change the way we work. There will be more and more collections of born-digital material, and everyone is going to have to process it, everyone is going to have to understand it,” says Sfirri.

“Eventually, every archivist will be a born-digital specialist."

Date

September 1, 2021