Diversity in the Stacks: Japanese Women Photographers Collection

Meeting Ishikawa Mao

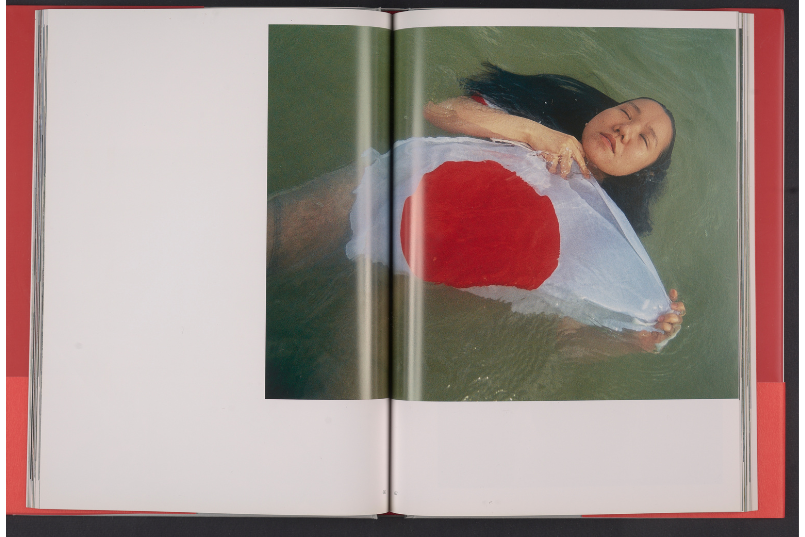

On an early spring day in March 2014, amidst the blossoming cherry trees, I was gallery-hopping in the Roppongi neighborhood of Tokyo with my mom, who was visiting me during my yearlong immersion in Japanese language training in Yokohama. While visiting Zen Foto Gallery, my eye was drawn to the exhibit on display, “Hinomaru o miru me” [“Here’s What the Japanese Flag Means to Me”]. The Okinawan photographer, Ishikawa Mao, had taken photos between 1993 and 2011 of Japanese people — including Okinawans, the Ainu, and Zainichi Koreans — engaging with the Japanese flag and expressing their complex relationships with Japanese identity. Ishikawa also included Taiwanese and Korean people in her project, given their countries’ colonization by the Japanese Empire (from 1895–1945 and from 1910–1945, respectively).

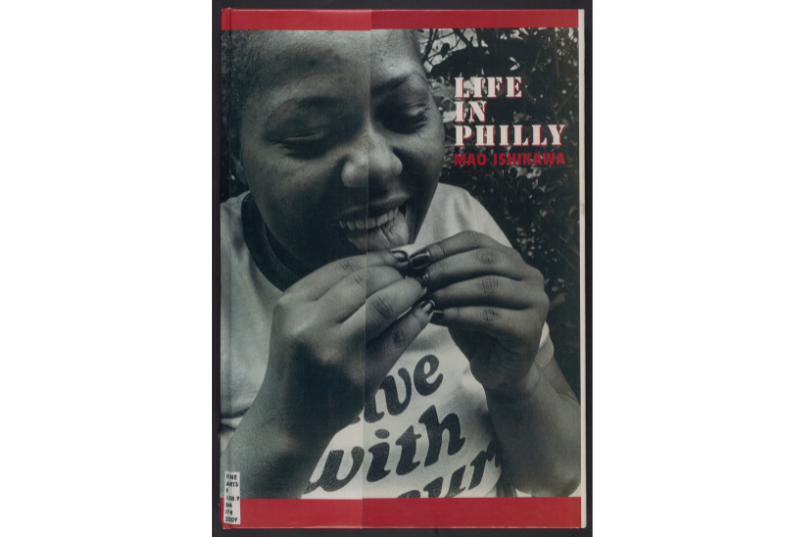

Stepping back from her riveting, raw portraits, I encountered Ishikawa Mao herself, who was at Zen Foto for the exhibit’s opening. She was warm and present, her fierce love for and dedication to Okinawa tangible even from our brief conversation. I learned later that Ishikawa had spent decades documenting Okinawans and the American military presence on their islands. She had even published a photobook, Life in Philly, with photos from her 1986 visit to Myron Carr, a Black American former soldier whom she had met in Okinawa, and his community in Philadelphia.

Ishikawa’s decades-long interest in those marginalized by mainstream society — due to race, ethnicity, occupation, class, and gender — in many ways exemplifies current collecting priorities of the Penn Libraries’ global collections. Fellow area studies bibliographers and I are striving to cultivate the Libraries’ collections that document and give platforms to underrepresented voices and those with complicated relationships to borders and national belonging. In particular, Ishikawa’s work points to a new collection at the Penn Libraries: the Japanese Women Photographers Collection.

Challenging the Canon

The 20th-century history of photography in Japan — and the telling of this history — has disproportionately emphasized the work of male photographers. To challenge this, scholars have been illuminating the role of Japanese women photographers throughout the decades; a recent example is Dr. Kelly Midori McCormick’s scholarship on postwar photography. Dr. Ayelet Zohar has shed light on Japanese photography during the Heisei era (1989–2019), which saw an unprecedented level of participation of female photographers, particularly in the 1990s and early 2000s. Exhibits, such as the recent “10/10 Celebrating Contemporary Japanese Women Photographers” (part of the Kyotographie International Photography Festival and supported by Women in Motion), have brought more visibility to female artists. This past June, McCormick and Dr. Carrie Cushman launched a bilingual digital humanities project that is also transforming access to and discovery of Japanese women photographers’ work: “Behind the Camera: Gender, Power, and Politics in the History of Japanese Photography.”

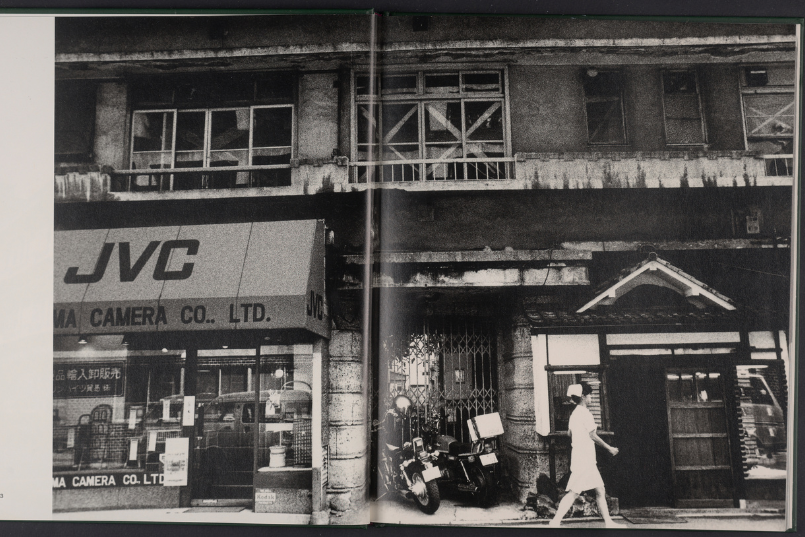

However, print collections of Japanese photobooks at institutions worldwide have continued to skew heavily toward male photographers such as Moriyama Daidō. Moriyama’s work exemplifies the are-bure-boke style — meaning “grainy, blurred, out of focus” — that developed in the late 1960s and is associated with the influential journal Provoke; he and colleagues like Araki Nobuyoshi arguably continue to dominate collections and the Japanese photographic canon alike.

The Penn Libraries is challenging this trend through the development of our Japanese Women Photographers Collection. After starting in my current position as Japanese studies librarian in July 2020, I was delighted to learn that previous librarians had been building our Japanese photobook collection for more than a decade. My predecessor, Dr. Molly Des Jardin, had built a distinctive collection of urban exploration and “ruins” (haikyo) photography, including works by female photographer Ōhata Saori, such as Sayonarasuru kakugo wa dekite iru? [Are You Ready to Say Good-bye?] and Haikyo to iu no sangyō isan. Additionally, Hannah Bennett, former director of Fisher Fine Arts Library, worked with Penn faculty member David Hartt to acquire a collection of first-edition imprints and artist books by Japanese photographers.

Over the past two years, I have worked to diversify the Penn Libraries’ Japanese photobook collection, developing it in both breadth and depth. For breadth, we acquired more than 120 publications by Zen Foto Gallery, which publishes photobooks by both established and emerging photographers, often in tandem with exhibits like Ishikawa Mao’s. The gallery, established in 2009 by British gallerist and collector Mark Pearson, frequently publishes multi-lingual editions, including first-edition imprints and reprints of important out-of-print works. As Russet Lederman notes in “Then and Now: Japanese Women Photographers of the 1970s and ’80s Revealed Through Their Photobooks”: “…Over the last few years a growing interest in Japanese photobooks from the 1960s to the ’80s has fueled an explosion in reprints, re-editions and reinterpretations of many difficult-to-find Japanese photobooks of the postwar period” — therefore disseminating Japanese women photographers’ work, which may have been previously overlooked, to a broader audience and prompting reevaluation of their important contributions. (See Lederman’s Behind the Camera module, “Postwar Photobooks by Japanese Women,” for her introduction to 41 photobooks by Japanese women.)

For depth in our collection, I have focused on strategic acquisition of women photographers’ works. Our collection now includes at least 105 works by and about Japanese women photographers, and it is rapidly growing. The collection is meant to be expansive — for example, it includes works by Japanese people living abroad, such as Takizawa Akiko — but is inevitably not comprehensive.

This collection includes not only recent acquisitions but also such works that the Penn Libraries previously acquired. I identified the latter items by searching our catalog by keywords, subject headings, and authors, working from various sources: lists of photographers I knew to be women or featured in scholarship like Zohar’s and McCormick’s, artist biographies on photobook vendors’ sites like that of Shashasha, and lists of women photographers that relate to the Behind the Camera project (which McCormick shared with me).

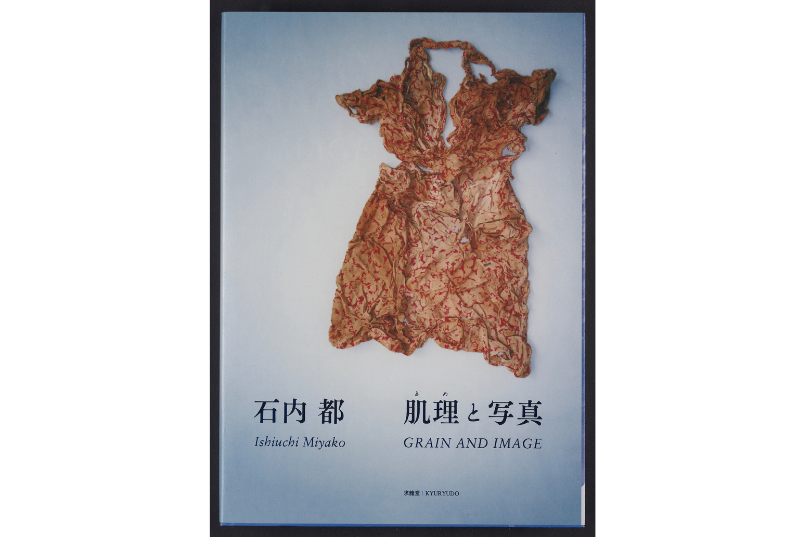

For example, we already had several works by the influential photographer and 2014 Hasselblad Award winner Ishiuchi Miyako (born in 1947 in Yokosuka, home to a US naval base). These included Club & Courts, Yokosuka Yokohama (2007), Hiroshima (2014), Furida ai to itami [Frida: Love and Pain] (2016), Shashin kankei (2016), Beginnings: 1975 (2018), and Miyako to Chihiro: futari no onna no monogatari (2019). To these works, we recently added four more books: Belongings (2015), Ishiuchi Miyako: Kinu no yume [Ishiuchi Miyako: From Cocoons] (2018), Kime to shashin [Grain and Image] (2018), and Yokohama gorakusō (2017).

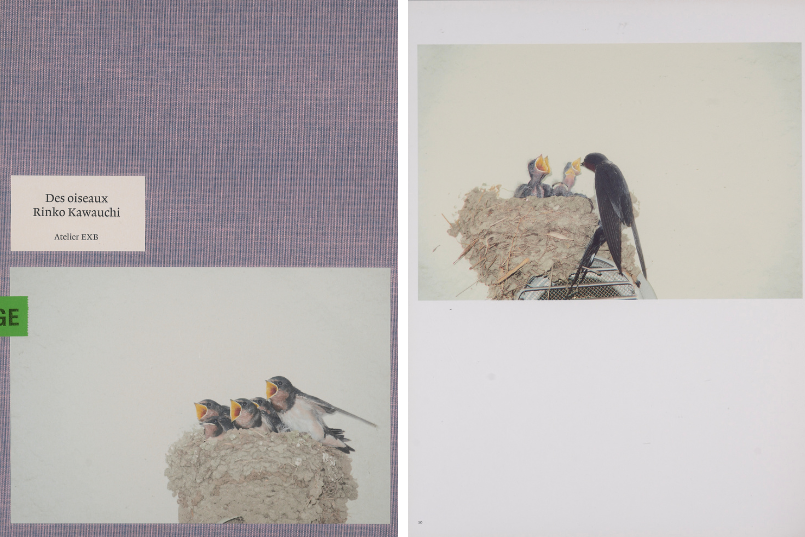

As with Ishiuchi’s work, the Penn Libraries already had some works by Kawauchi Rinko (born in 1972) — AILA, Halo, and When I Was Seven — and recently added As It Is and Des Oiseaux.

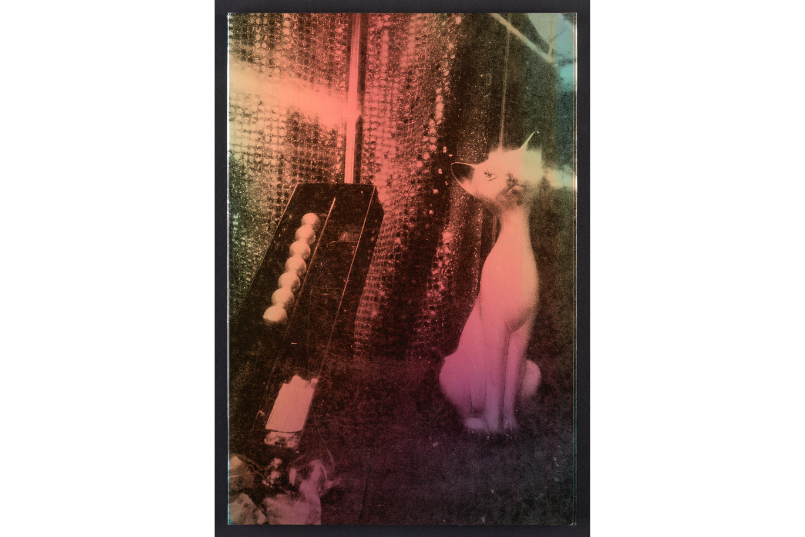

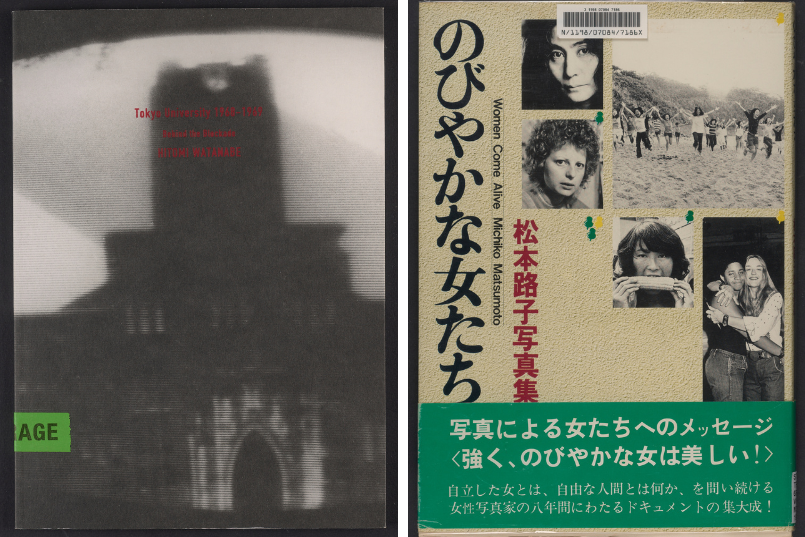

Other new acquisitions range from works by the emerging experimental artist Tokyo Rumando (born in 1980) to reprints of important, out-of-print books, such as Watanabe Hitomi’s Tōdai 1968-1969 Fusa no uchigawa [Tokyo University 1968–1969 ― Behind the Blockade], a photobook documenting the student protest movements of 1968–1969 in which she participated. Related to Watanabe’s work is Matsumoto Michiko, Nobiyaka na onna tachi: Matsumoto Michiko shashinshū [Women Come Alive] (1978); like Watanabe, Matsumoto documented social protest movements of the 1970s. This particular book by Matsumoto is fascinating (and “meta”) in that Matsumoto documents women photographers and other artists, such as Yoko Ono.

We also added nine works by Nishimura Tamiko (1948), discussed by Lederman vis-à-vis Ishikawa Mao and Ishiuchi Miyako.

The process of discerning “women” photographers’ works is ongoing and imperfect: I may have made incorrect assumptions about artists’ gender. (To readers who identify errors or omissions: please contact me!) Additionally, I have grappled with the issue that a “Japanese Women Photographers” Collection presumes, reflects, and reifies a gender binary that does not accurately capture the range of gender expressions and may not reflect artists’ identity. Still, I believe that it is worthwhile to undertake this effort — given that the norm and standard in canonical Japanese photography was equated with male photographers for so long.

Finding the Japanese Women Photographers Collection

An important part of establishing this collection is making it discoverable: how can patrons interested in the topic identify Japanese women photographers’ works if they don’t already know about Japanese photography, especially given that these works are scattered among our different library locations and different classification ranges, and many books lack a unifying subject heading? For example, there are only four works in the Franklin catalog with the Library of Congress Subject Heading, “Women photographers--Japan.” To address such discovery challenges, I worked with Information Processing Center experts Beth Camden and Mike Williams to create a virtual “collection,” which appears in the books’ Franklin records as the “Contributor.” You can search for this collection in Franklin by entering “Japanese Women Photographers Collection” in the search bar (in quotes) or clicking here.

This collection is still a work in progress. Given that the majority of the works have been acquired recently, amidst global shipping slowdowns and processing backlogs at the Libraries due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many are not yet available for borrowing or do not yet have complete bibliographic records.

The Penn Libraries plans to scale up our acquisitions going forward. Ideally, our collections will include photography from the early 20th century through contemporary Japan, printed in a range of media types, from rare artist-book-type and first-edition photobooks to more commercially available photobooks and exhibition catalogs. Most significantly, our collections will continue to reflect a vast range of artistic and social visions by Japanese women who may or may not have had a visible platform during their active years as photographers.

Please see the Japanese Women Photographers Collection to learn more — and keep checking back as we add and process more works!

Diversity in the Stacks aims to build library collections that represent and reflect the University’s diverse population.

Banner image: Ishikawa Mao, Hinomaru o miru me (Tokyo: Miraisha, 2011), cover.

Date

August 24, 2022