Diversity in the Stacks: Kurdish Collections

Diversity in the Stacks aims to build library collections that represent and reflect the University’s diverse population.

While a few libraries in North America have sought and acquired Kurdish materials, Kurdish collecting is inconsistent across the academic and research library landscape. This is largely due to the marginalized status of the Kurdish language and publishing in the Middle East, and by extension the peripheral position Kurdish and Kurdish Studies holds in Middle East Studies. As part of combating this trend, the Penn Libraries’ Kurdish collecting efforts build upon previous work from Middle East bibliographers as the Libraries seeks to ensure greater representation for the peoples and languages of Kurdistan.

Historically speaking, early works on Kurdish Studies in the Penn Libraries trickled in with other collections dealing with Iran and were chiefly on Kurdish philology and linguistics; examples of these materials include the works of Oskar Mann such as Die mundarten der Mukri-kurden, Ely Soane’s Grammar of the Kurmanji or Kurdish language, and Maurizio Garzoni’s Grammatica e vocabolario della lingua Kurda. In the 1990s, Kurdish books from Iran were added to the collection thanks to the Library of Congress’ PL-480 Program via its field office in Islamabad, Pakistan, where such materials were regularly collected. Following the lifting of sanctions on Iraq in 2003, the Libraries began to systematically collect Kurdish books from this region through commercial suppliers and gifts; this was in response to increased faculty and student interest on Kurdish matters.

But what is “Kurdish” collecting? The world’s Kurdish population is largely split across the four countries of Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria, with smaller populations across the Middle East and Caucasus. It also includes significant diaspora communities, notably in Germany, Sweden, and France. Sweden in particular is home to a number Kurdish writers and publishers of Kurdish writings. The two main Kurdish languages are Kurmanji and Sorani, with the additional languages of Zazaki and Gorani. While Sorani now holds an official status in Iraq, Kurdish language and publishing in the neighboring Middle Eastern countries has been subject to varying levels of (il)legality and repression. There are several Kurdish publishing houses that can be honed in on to collect Kurdish materials, although more mainstream publishers also produce Kurdish publications.

Poetry is foundational to Kurdish literature, as it is for neighboring languages. Ehmedê Xanî’s Mem û Zîn, an epic poem dating from the 17th century, holds an important place in both Kurdish literary history and nationalist thought, since it references the lack of a Kurdish state. There are several editions of this text: one edition includes both Mehmed Emîn Bozarslan’s transcribed version and Turkish translation from 1968. This book is cited as important both for the history of Kurdish publishing as well as literary history. According to Bozarslan half of this first run was confiscated by the police and destroyed; Penn Libraries holds the second edition from 1975.

In looking at other existing translations, I was interested to discover a Persian translation from 1962 by ʻUbayd Allāh Ayyūbiyān, derived from a version compiled by German Iranologist Oskar Mann. The earliest Arabic translation I could find was completed by Muḥammad Saʻīd Ramaḍān al-Būṭī in 1982. The Libraries does not hold a copy of this translation, but we do have an Arabic translation by Jan Dost (Jān Dūst), a writer and poet from Syrian Kurdistan.

Dengbêj, an oral tradition of sung storytelling, is another important form of Kurdish literature. The Libraries recently purchased compilations of prominent dengbêj storytellers, such as İbrahim Şahin and Ömer Güneş’s Dengbêj Şakıro and Dengbêj Reso, both brought to my attention by Middle East Studies scholar Metin Yuksel in a talk he gave last year. Works acquired on the subject include Hilmi Akyol’s writings on dengbêj and folklore. While dengbêj has mostly been a male-dominated artform, there have been women performers such as Ayşe Şan, a Kurdish singer and subject of the book Prensesa bê tac û text Eyşe Şan.

Looking at modern Kurdish literature and other recent creative works raises interesting questions around identity, genre, and ownership. Clémence Scalbert-Yücel raises a number of questions around defining and classifying Kurdish literature in Turkey. In particular she asks, “is Kurdish literature written exclusively in Kurdish or can other languages be used?” going on to argue that Turkish language writers do contribute to Kurdish literature. The diversity of Kurdish populations means that a Kurdish literature compilation could bring together works in multiple languages and scripts. There are also a number of prominent writers of Kurdish background or identity whose writings and work are incorporated into larger Arabic or Turkish canons, including Yaşar Kemal of Turkey and Salim Barakat of Syria. Yaşar Kemal is quoted as saying, “I am Kurd too, but I am not a Kurdish writer.” Artists like Ahmet Kaya and filmmaker Yilmaz Güney achieved national acclaim in Turkey, and dealt with Kurdish issues in their work, but library subject headings designate them as of Turkey without mentioning the Kurdish people or Kurdish language. I have written about issues around cataloging Kurdish materials elsewhere. Certainly, these artists can identify in more than one way or be claimed by multiple communities, but it is unfortunate when library classifications contribute to erasures.

Despite obstacles like repression and lack of Kurdish language education, writers have labored to establish a modern Kurdish literary tradition that crosses borders and languages. Mehmed Uzun, described as Turkey’s first Kurdish novelist, wrote his first novel in the 1980s while living in Sweden. Until recently, the Libraries was lacking his works, but we now have a selection of his works in Kurdish and Turkish, including novels, literary criticism, and the Kurdish Literature anthology he compiled.

While Uzun wrote in Kurdish, some authors write in Turkish or other languages and still establish themselves in the field, since many Kurdish people in Turkey don’t have access or fluency in Kurdish language. Suzan Samanci, a woman writer from Diyarbakir, has written about the civil war and other events impacting the Kurdish people but in the Turkish language, and her works have been translated from Turkish into Kurdish.

Given the difficulties around learning and teaching Kurdistan, translations of Kurdish language works are vital and can significantly expand the audience for a work. Bakhtiyar Ali's (Bextiyar ʻElî) I Stared at the Night of the City, a remarkable novel steeped in magical realism and political commentary, is the first novel to be translated from Sorani Kurdish into English.

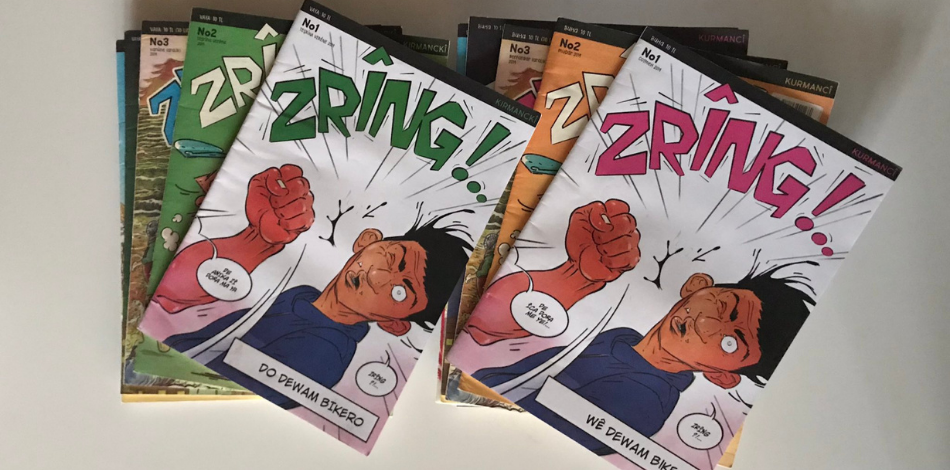

The Libraries also holds journals and periodicals in Kurdish or on Kurdish Studies. Recent additions include subscriptions to Zrîng!.., a comic published in both Zazaki and Kurmanji, which I learned about through British Library curator Michael Erdman’s tweets, and Kürt Tarihi, a predominately Turkish language publication that covers Kurdish history. Modern reprints of historical Kurdish newspapers and magazines include the first Kurdish newspaper, Kurdistan, reprinted as Kurdistan: rojnama Kurdı̂ ya pêşı̂n, and Jîn: Kovara Kurdî-Tirkî 1918-1919.

Kurdish holdings at the Penn Libraries also cover topics like history, religion, politics, and human rights, and include formats such as video and sound recordings. Developing our Kurdish collection has been informative and rewarding; while I try to collect for the Middle East in a way that reflects the multiculturalism and diversity of the various areas represented, honing in on Kurdish collecting has proved the value of taking a more focused approach. Visibility in cataloging and metadata is also very important for Kurdish library resources, so I am grateful for the hard work of the Penn Libraries’ Global Studies Technical Services team. I hope that these historical holdings and recent additions will support Kurdish studies and be of interest to readers and researchers of various fields!

Special thanks to former Middle East Studies Librarian William Kopycki for additional content for this post.

Date

January 25, 2022