Explore a lesser-known – but still very active – Germanic language

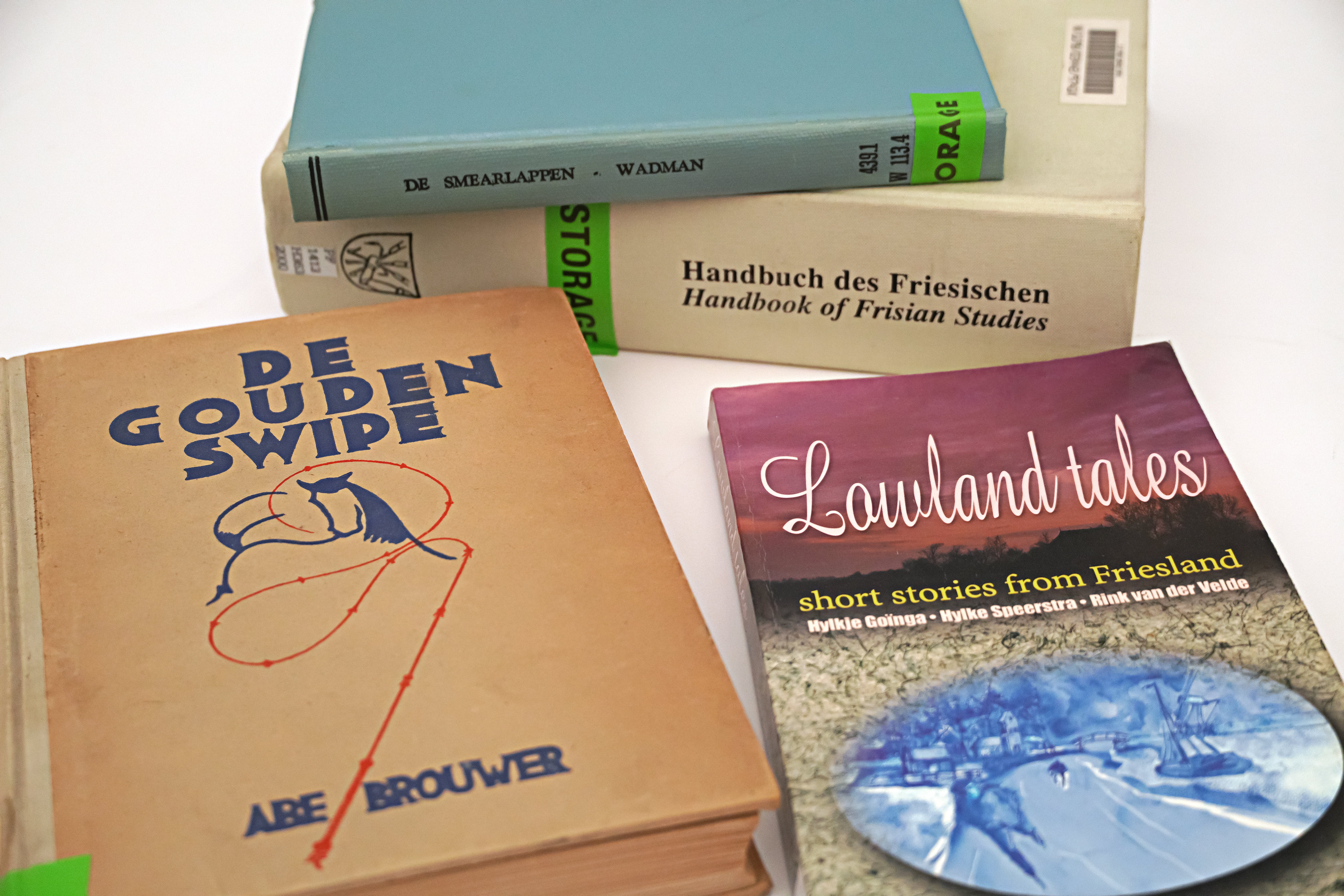

Penn is home to the largest library collection of Frisian-language literature outside of Europe.

The Germanic language that is often the least known to Americans is from the edge of a small corner of continental Europe, where it is spoken on coastal islands with sandy dunes and grassy knolls, quiet villages with brick lanes, and towns lined with canals. This is Friesland, or Fryslân, home to the Frisian people and the Frisian languages. Frisian is a group of languages spoken by about 500,000 people along the windswept North Sea coast in the Netherlands and Germany. The West Frisian language, spoken on the North Sea islands and northern coast of the Netherlands, is commonly referred to as simply “Frisian.” Frisian is often said to be the Germanic language closest to English, grouped together with English as an Anglo-Frisian language, rather than with Dutch or German, which usually fall under the label North Sea Germanic languages. In fact, in Frisian, one might hear a saying which, when spoken, may sound convincingly similar to English: “Bûter, brea, en griene tsiis is goed Ingelsk en goed Frysk.” (Butter, bread and green cheese is good English and good Fries.)

While the Penn Libraries may be an ocean away from the home of “good Fries,” Penn is home to the largest library collection of Frisian-language literature outside of Europe. An analysis of languages in the Penn Libraries’ collections revealed more than 1,300 Frisian books, a larger collection than the Library of Congress, and one that is comparable in size only to the Frisian collections at the New York Public Library. The majority of these books are printings of what the small, specialized field of Frisian Studies refers to as “post-classical texts” from the early 1900s. Most survive as pamphlets or small books unique to Frisian’s minority-language publishing culture and its small but vibrant literary scene that celebrates its local folklife. Around one-third of the Penn Libraries' collection of Frisian-language materials is from the 1920s or earlier, old enough to be in the public domain.

Frisian essentially serves as a living historical linguistic link between English and other Germanic languages. Today, it is a living language that shares official status with the Dutch in the province of Friesland, where many locals are effectively bilingual in both Dutch and Frisian. Dutch has a long history at Penn and was first taught at Penn in 1896. Gertrude Reichenbach (1913-2001), a lecturer of Dutch, came to Penn in 1969. She introduced the Dutch minor in 1978 and the major in 1983. Before Reichenbach’s arrival an African-American literary scholar and Germanist, Marron Curtis Fort, (GR'65) (1938-2019) was Penn’s most active scholar with an interest in Frisian. Fort was an expert on Low German and Frisian who authored the first dictionary of Saterland Frisian, a now-endangered East Frisian dialect spoken in a linguistic enclave in lower Saxony. Fort’s advisor was Alfred Senn (1899-1978), a Germanist at Penn from 1936 to 1969 who also taught Slavic and Baltic languages. Fort went on to become a naturalized German citizen and to receive medals of honor from German cultural organizations for his work in linguistic preservation and documenting Frisian.

The works owned by the Penn Libraries are largely West Frisian rather than the Saterland Frisian that was of interest to Fort, and they consist mostly of small volumes of poetry, plays, songs, short tales, proverbs, and folklore, most less than 100 pages in length. We also have a few lengthier reference materials like dictionaries and word lists, perhaps of use in comparative linguistics. Many items are labeled pamphlets, published in the larger towns of Friesland, mainly Leeuwarden, Friesland’s provincial capital, and many items in the collection pre-date a standardized Frisian way of spelling. These post-classical texts may be important for scholars who are interested in updating or completing studies of Frisian phonology, morphology, spellings, and place names.

These types of publications reflect a culture in which minority-language promoters emphasized hyperlocal literary gatherings in private homes or at small village inns, where community members performed plays and shared poetry readings, songs, and stories with each other. This culture of local get-togethers and small-scale theater productions explains why these older texts in Frisian are often slim, brief, and plain, having been published in small runs. A scholar of both Dutch and Frisian literature, Joke Corporaal (b. 1979), in her 2018 book As Long as the Tree Blooms: A Short History of Frisian Literature 800-present, writes about the emergence of a reinvigorated movement in support of Frisian-language publishing and the written word which began in the 19th century. She writes about Frisian social gatherings around small theater performances and group readings especially during the long nights of the winter season, with poetry, song, or theater pieces often featuring folksy or humorous characters. This became a way to assert Frisian identity and pride.

Frisian is by no means a threatened language today. It is in active use in Friesland, spoken, written, taught, and studied. Researchers note that, in Friesland, where Frisian-Dutch code switching is common, linguists have noticed a shift toward more of a Dutch-sounding pronunciation among Frisian speakers.

Not surprisingly, academic study of Frisian is limited. There is graduate-level study at the University of Groningen, Frisian-language education at Stenden University in Leeuwarden, and courses on offer at the University of Amsterdam and from the AFUK (Algemiene Fryske Ûnderrjocht Kommisje) in Leeuwarden. Other universities outside Friesland have taught Frisian, at Amsterdam, Utrecht, and Leiden. Oxford offers an Old Frisian Summer School for Ph.D. students interested in the history of Germanic languages. The Fryske Akademy in Leeuwarden is focused on promoting study of Modern Frisian, while the Frysk Ynstitut at Groningen is mainly concerned with Old Frisian and Frisian literature of the 15th-18th centuries.

Today many of the oldest items in Frisian that Penn owns may be in the public domain and available through Google Books, the Dutch online repository Delpher, or in the digital collections of the Frisian Historical and Literary Centre. Yet they represent an aggregate collection of Frisian-language literature not unlike the comprehensive collections at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, and other libraries outside of the Frisian-speaking regions of the Netherlands, that have contributed to Google Books and Delpher, such as the University of Amsterdam, University of Utrecht, and Leuven University.

The Penn Libraries continues to purchase select works about the Frisian language, as well as select works of poetry and literature. This close linguistic cousin to English and its literature lives on at Penn, where it can offer insights into the evolution of Germanic languages, including the development of the English we speak today.

Texts in Frisian

- Dykstra, Waling. De silveren rinkelbel (The Silver Rattle), 1866.

Dykstra (1821-1914) was an early figure in the Frisian Movement (De Fryske Beweging) of the 19th century. The Silver Rattle, first published in 1856, is considered the first Frisian novel and a classic.

- Broerren Halbertsma (The Halbertsma Brothers). Rimen en teltsjes (Rhymes and Tales), 1918.

The Halbertsma Brothers, Joast (1789-1869), Tsjalling (1792-1852), and Eeltsje (1797-1858), are founders of the Frisian Movement, promoting Frisian language and literature. Rhymes and Tales is a compilation of their Frisian romantic poetry and stories, and a Frisian literary classic.

- Schurer, Fedde. Fersen, 1934.

Schurer (1898-1968) was a popular Frisian poet who, with his friend Douwe Kalma (1896-1953), grew the youth movement organization, Jongfryske Mienskip, during the 1910s, Fersen was his debut. He went on to become active in political and literary circles, campaigning against nuclear weapons and for Frisian language rights.

- Brolsma, Reinder. It Heechhof (The Farm on the Mound), 1939.

The Farm on the Mound is the first novel of newspaper journalist and painter Reinder Brolsma (1882-1953), who became an important writer between World War I and World War II . This is the first book in “The High Court Trilogy,” about a struggling Frisian farmer, which continued with It Aldlân, (The Old Country, 1938) and Richt (Justice, 1947).

- Kloosterman, Simke. De Hoara's fen Hastings (The Hoara Family from Hastings), 1940.

This is the first modern novel in Frisian written by a woman author, Simke Kloosterman (1876-1938). Set in a fictional village called Hastings, the novel follows the story of a local Frisian family.

- Brouwer, Abe. De Gouden Swipe (The Golden Whip), 1943.

Brouwer (1901-1985)’s first novel is an example of wartime literature that extolled Frisian rural life, with farming and pre-industrial themes from the countryside. It was later made into a film.

- Wadman, Anne. De smearlappen (The Perverts), 1963.

Wadman (1919-1997) is the most famous 20th century figure in Frisian literature for his novels and poetry. He was part the editorial staff of the Frisian literary journal De Tsjerne and known for provocative reviews. Wadman wrote The Perverts in a confessional, casual style, as a parody of Frisian rural fiction, and critics found its sexual content and directness scandalous. It received wide attention in the Dutch literary press, unusual for a Frisian-language book translated to Dutch, also for its feminist themes.

- Goïnga, Hylkje, Hylke Speerstra, and Rink van der Velde. Lowland tales: short stories from Friesland, 2000.

A translated volume of stories with contributions from feminist author Goïnga (1930-2001), best-selling Frisian oral history writer Speersta (b. 1936), and prolific author Van der Velde (1932-2001), who was one of the most widely read Frisian writers of the 20th century. As a journalist he wrote for both the Frisian and Dutch press, as well as short stories and 25 novels.

- Postma, Obe. What the Poet Must Know: An Anthology, 2004.

A revered and prize-winning poet, Postma (1868-1963) was known for his simple, powerful, mysterious style, as well as for publishing for a span of over 60 years.

- Bruinja, Tsead. De berte fan it swarte hynder: een keuze uit de Friese gedichten (The Birth of the Black Horse: A Selection of Frisian Poems), 2010.

Bruinja (b. 1974) is a modern stage poet who sketches colorful, romantic poems that deal with an underlying sense of personal danger and dread in everyday Frisian life, as evidenced in this collection. He publishes extensively in both Frisian and Dutch, and organizes poetry performances and festivals.

- Tiemersma, Koos. De ljedder (The Ladder), 2010.

Novelist Tiemersma (b. 1952) wrote his character-driven, humorous debut novel in 2002, and received the first Rink van der Velde literature prize.

- Hindriks, Elske. In kop as in almenak (A Head Like an Almanac), 2013.

A writer at the first Frisian-language Internet magazine, Kistwurk Hindriks (b. 1957) broke through in 2013 with A Head Like an Almanac, in which she writes about her family history and of inland shipping, skippers and their iconic Frisian flat-bottomed, wooden sailboats, once used for moving cargo.

- Zandbergen, Ale S. van. Littenser merke (The Littens Market), 2017.

Van Zandbergen (b. 1956) wrote this prize-winning coming-of-age novel about a Frisian village boy in the 1960s and 1970s, with flashbacks to the 1830s and the impact of the Secession of 1834, a split in the Dutch Reformed Church.

- Riemersma, Trinus. De reade bwarre (The Ginger Tom), 2022.

Riemersma (1938-2011), a writer, columnist, and former editor of the literary journal De Tsjerne, originally published The Ginger Tom in 1992, and it immediately gained cult status among readers, with many references to Frisian culture and history that have also made it difficult to translate, even into Dutch.

Works on Frisian literature

- Munkse, Horst Haider. Handbook of Frisian Studies, 2001.

The first systematic overall description of Frisian studies from the early runes to Frisian as a European minority language. The central focus is on the West, East and North Frisian dialects in the Netherlands and Germany, standard West Frisian, the history of the Frisian languages and literatures and Old Frisian in the Middle Ages. (Publisher's description)

- Bruinsma, Ernst, Alpita de Jong and André Looijenga. Swallows and Floating Horses: An Anthology of Frisian Literature, 2018.

Swallows and Floating Horses is a comprehensive bilingual anthology of Frisian literature, including nearly a hundred and fifty poems and prose extracts from all historical periods and all areas where Frisian is spoken and written, accompanied by new translations into English by a group of respected translators. (Publisher's description)

- Corporaal, Joke. As Long as the Tree Blooms: A Short History of Frisian Literature, 2018.

A continuous history of Frisian literature, organized into seven chapters, published by Tresoar, a regional historical center in Leeuwarden, Netherlands which manages digital archives about Friesland and its literature. A companion website is available at fryskeliteratuerskiednis.frl.

Date

February 12, 2025