Inside the Bollinger Digital Fabrication Lab

How the 3D printing team at the Holman Biotech Commons is stimulating scientific and medical innovation at Penn.

Lexi Voss and Varvara Kountouzi, both of the Penn Libraries’ Holman Biotech Commons, are integral players in innovative, multidisciplinary, research happening every day at the University of Pennsylvania. Employing their knowledge and expertise with the 3D printing technology used in the Judith and William Bollinger Digital Fabrication Laboratory, they have worked with researchers and clinicians on projects that are helping scientists understand ant behavior, improving the effectiveness of veterinary surgeries, and even prototyping surgery-free options for improving infants’ quality of life.

Since 2019, Voss has served as the Visualizationist at the Biotech Commons. In this role, she manages the day-to-day operations of the Bollinger Lab and consults with students, faculty, staff, and clinicians from across the University who are interested in using its 3D printing technology. She, along with Kountouzi, head of Bollinger Lab, have seen the way 3D printing has changed scientific research in the past few years.

“3D printing has revolutionized the whole field in terms of innovation,” says Kountouzi. Before 3D printing became broadly available, those who wanted to test out a new device that might be used in research or clinical care might find that manufacturing something totally new, even just to use it in their labs, cost too much money or took too much time to be practical. Now, working with an expert like Voss, relatively inexpensive materials, and a 3D printing lab, early-career researchers, grad students, and even undergrads can experiment and innovate in a way they couldn’t previously.

3D printing has also fundamentally changed how students in healthcare professions learn and work with patients. The Bollinger Lab is often asked to print anatomical models of human hearts, the bronchi of the lungs, and more. Sometimes, they even 3D-print models based on a specific patient so that doctors can more easily plan and practice surgeries. Kountouzi observes, “Even today, when virtual visualizations like MRIs are so powerful, people still find that holding an object in their hands makes a big difference.”

In order to better understand the impact Voss and Kountouzi have made on the scientific community, we sat down with the pair to learn more about some of their favorite 3D printing projects of the last few years.

Helping dogs improve their stride

Anna Massie, Assistant Professor of Orthopedic Surgery at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, came to the Bollinger Lab looking for a way to help one particular patient: a dog with bowed legs. Correcting a dog’s bowed legs can make a big difference to their quality of life, but the surgery itself can be tricky because it requires a surgeon to cut a very precise wedge out of the animal’s bone. Before putting this particular puppy under the knife, Massie and her colleagues wanted to ensure that they would get it right. What they needed was a way to practice on a dog’s leg that was exactly like that of their patient.

That’s where Voss and her 3D printing expertise came in. She showed Massie how to extract data from a CT scan of the dog’s leg and used it to print exact replicas of the leg bone, which the veterinary surgeons could then use to practice. Amélie Ya Deau, a third-year veterinary student studying under Massie and Penn’s Staff Veterinarian Thomas P. Schaer, had the idea to further expand the reach of the project. She used a similar process to create a model of the dog’s leg that could be used as a guide during the actual surgery. While 3D printed surgical guides are commonly used across campus — at the Dental School, for example — this idea is in its infancy in veterinary medicine. Ya Deau presented about the project at a national veterinary student conference in summer of 2021, and at Penn Vet’s Student Research Day this past spring. She, Massie, and Schaer plan to wrap up the project in January and hopefully publish their findings.

The ants go marching

Can you teach an old ant new tricks? That, in essence, was the question Shelley Berger and her team of researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine were in the process of asking when they approached the Bollinger Lab. In an ant colony, workers are genetically predisposed to taking on certain jobs; for example, some of them are food collectors, and some of them are nurses for ant larvae. But is it possible to manipulate an ant into switching jobs? With the help of this unassuming square chamber designed and printed by the Bollinger Lab, they discovered that the answer was yes.

This ant chamber is just one of many kinds of custom lab equipment that the Bollinger Lab produces for Penn researchers. It isn’t uncommon for scientists to need something custom-made to conduct their experiments: a clasp that holds a specifically-shaped syringe in place, a more ergonomic handle, or a unique box like this one. Before 3D printing, a scientist might have to go to a machinist, or a welder, or even a carpenter to get the piece made. Now, with the help of the 3D printing lab, they can get these materials made much more quickly and easily. And if the equipment breaks, they can easily have it replaced: the Bolliger lab just needs to use the 3D file to print a new one.

Can you hear me now?

Kountouzi considers InfantEar to be the “flagship project” of the Bollinger Lab. In 2015, not long after the lab received its first 3D printer, Scott Bartlett of the Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania worked with staff on a device he was developing that offered a non-surgical method of correcting congenital ear anomalies in infants. The lab printed both prototypes of the device itself and models of ears that featured common deformities. Today, InfantEar is manufactured and sold by TalexMedical, and used by pediatric plastic surgeons all over the country.

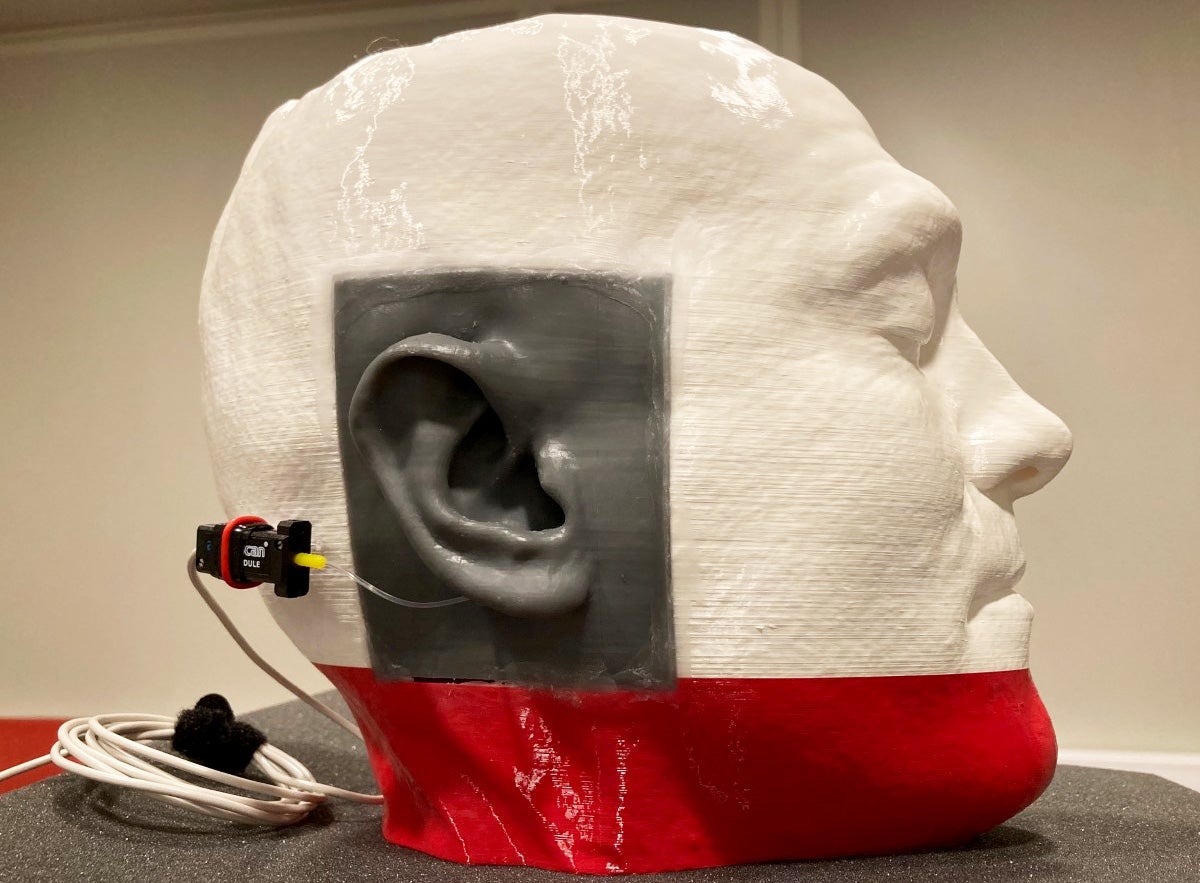

The partnership between Bartlett and the Bollinger Lab didn’t end when InfantEar hit the market. More recently, Voss has been working with Liana Cheung, a research fellow at CHOP, on a project that is further expanding the study of infant ear shapes. This time, the goal was to determine how different ear shapes absorbed sound differently. Along with helping her print the numerous models she designed, Voss and Cheung also had to select the right material for the ears, and even designed and printed a model of a human head to which the ears could attach.

Voss sees the work with Bartlett’s team as a great example of the way the Bollinger Lab has grown over the years. “We’re able to say, okay, we did this thing with this lab previously, and now we can do this next cool thing because we have better equipment and more expertise.”

Working with the Bollinger Digital Fabrication Laboratory

These are just a few of the projects Voss and Kountouzi have worked on over the years. In the past year they have completed 594 3D printing jobs. While the bulk of their work involves collaborating with scientific and medical graduate students, faculty, researchers, and clinicians, the Bollinger Lab offers 3D printing services for any project related to courseware or academic research.

Inspired to begin a 3D printing project of your own? Voss’ biggest tip is to start thinking through the design even before you start experimenting with 3D software. “Sketch! I never get enough sketches,” she laughs. “Make paper models and clay models.” She emphasizes that doing this kind of design thinking will make it easier for you to imagine how the object will look and function after it has been printed.

Once you have a clear sense of your design, set up a time to meet with Voss. She can show you how to turn your models and sketches into a 3D design using software like Tinkercard, discuss available materials, and more. For more tips and information, see our guide to 3D printing at the Bollinger Digital Fabrication Lab.

Featured image: A 3D printed dog leg model created by the Bollinger Lab.

Date

December 2, 2022