The Penn Libraries Acquires the Personal Papers of Historian and Activist Elizabeth Fee

David Barnes, Associate Professor of the History and Sociology of Science at the University of Pennsylvania, often thinks about the ways that history, and particularly history of science, can help inform the present.

“From the beginning of my career I’ve thought that history is political and my work should mean something. I believe that my teaching and my scholarship should inform struggles that are happening today. But it’s really hard to do well.”

This interest has seeped into many of his scholarly projects; in particular, he has advocated for the preservation of the Philadelphia Lazaretto, seeing the historic site where people and goods were once held in quarantine on their way into the city as a place to talk about both the past and the present of medicine, health, and inequality.

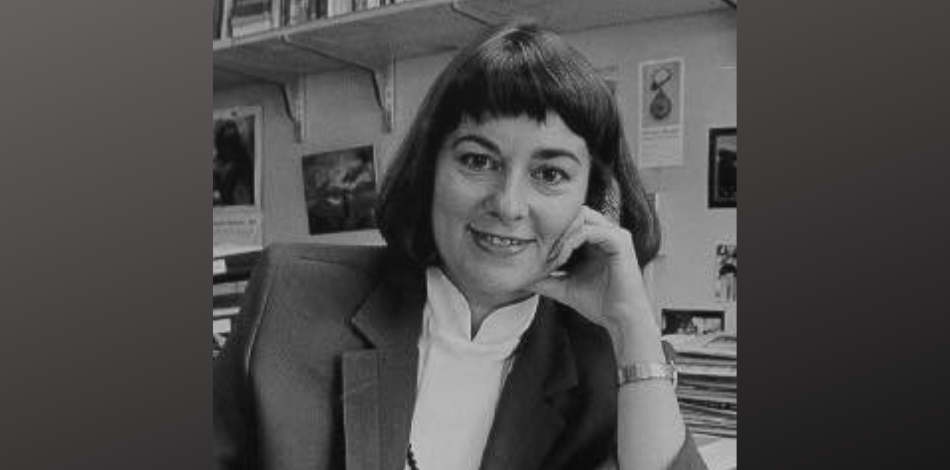

According to Barnes, one scholar stands above the rest for her commitment to the principles that guide his work today: pioneering historian and health activist Elizabeth Fee. Fee died in 2018, and her personal papers were donated to the Penn Libraries earlier this year. The donation was made by Mary Garofalo, Fee’s surviving spouse, who gave additional funds to the Penn Libraries to support the hiring of an archivist who will process the collection. It joins the Walter Lear papers, an extensive collection that includes records from the Maternity Care Coalition, the Medical Committee for Human Rights, and the Physicians Forum, as part of the Libraries’ growing collection of materials charting the history of public health activism.

“I can’t think of any historian who [paired activism and scholarship] better than Liz Fee,” says Barnes. “It came from her decades of involvement with various movements. She didn’t come in from the outside and say ‘I have a PhD. Let me tell you the meaning of what you're doing.’ It was organic for her.”

As a leading scholar of the history of public health, Elizabeth Fee spent 21 years as a professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, and then worked as a historian at the National Library of Medicine from 1995 to 2018. She served as an editor at the American Journal of Public Health, curated a number of celebrated exhibits, and wrote or co-wrote thirty scholarly books and hundreds of articles on topics ranging from the history of fighting malaria in China to the impact of lead paint on communities in mid-20th century Baltimore. According to Mary Garofalo, Fee was particularly proud of her work on lead paint, which was subsequently used by legal professionals in a series of court cases that sought to hold paint and pigment manufacturers accountable for lead poisoning around the world.

Fee is probably most known for her work documenting and analyzing the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Out of her work came two co-edited volumes: AIDS: The Burden of History and AIDS: The Making of a Chronic Disease. Published in 1988 and 1992, respectively, the books serve as important examples of documenting history that’s still in progress in ways that are thoughtful, comprehensive, and non-exploitative. “AIDS is a good example of how Liz was able to connect scholarship and engagement,” says Barnes. “At the time of the epidemic, a lot of academics were posturing as ‘activist scholars,’ and their historical scholarship was shallow and really hasn't stood the test of time. But a few scholars really did stick with it over the years and were able to place AIDS in a larger historical context. And Liz was one of them.”

Lynne Farrington, Director of Programs and Senior Curator for Special Collections in the Penn Libraries Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts, is also excited about the opportunities this new acquisition presents. She says that one thing that makes the Fee papers so fascinating is that they document the often-difficult process of conducting complex, socially relevant research projects. As an example, Farrington points to Fee’s correspondence regarding two books she wrote that garnered some controversy: a history of the World Health Organization and a history of the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health. Both tackle powerful institutions--including one that was, of course, her employer--without pulling punches. “She was willing to go out and say things,” says Farrington. “She was pretty courageous.”

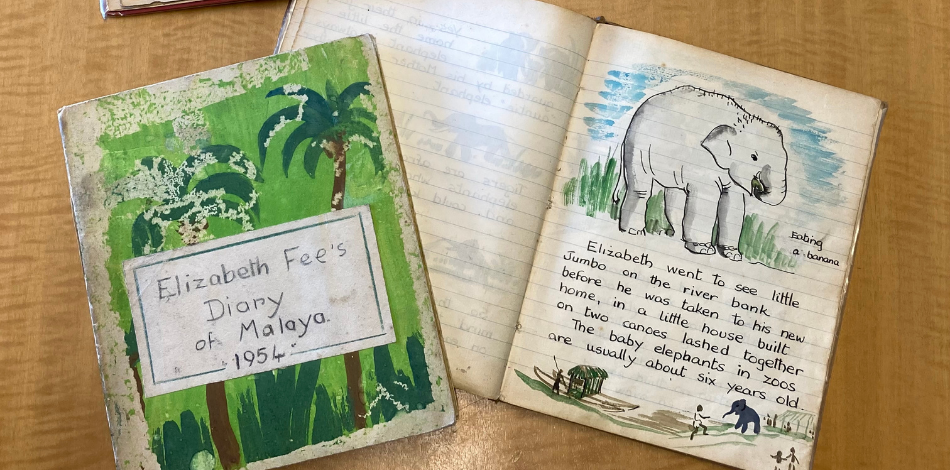

The donated papers chart fascinating moments in Fee’s personal life as well as her professional one. “It’s a collection about a whole person, about how she was brought up and how that influenced her,” says Garofalo. Fee’s parents were missionaries in China who lived through the country’s Japanese occupation during World War II. In a series of watercolor paintings, her mother documented the experience of that harrowing time, as well as the family’s international travels through South and Southeast Asia in the 1950s and 1960s. The collection also includes documents from the family’s time living in Belfast, Ireland, where Fee’s father was a Methodist minister.

Though Elizabeth Fee had no formal personal or professional connection to the University of Pennsylvania, Garofalo quickly realized that the Penn Libraries would be the perfect home for Fee’s papers. Notably, Fee was a close friend and professional collaborator of Walter Lear, whose papers are already housed at the Libraries. An activist and a physician who lived in West Philadelphia before his death in 2010, Lear was known for his indefatigable dedication to social causes and for being, as Barnes puts it, “a clearinghouse of information” about public health and social justice organizations. With the addition of Fee’s papers, he hopes that the Penn Libraries can become a “mecca” for scholars researching the history of health activism. Barnes is also sure that his students will find it valuable; he regularly teaches an undergraduate research seminar on the history of health activism that is centered on the Lear papers, and he is certain that the Fee papers will make an excellent addition to the class in the future.

Garofalo was impressed by the Libraries’ dedication to making materials available to students and researchers. Fee was an enthusiastic teacher who was well-loved by her students, and who encouraged her staff at the National Library of Medicine to continue pursuing educational opportunities. Thanks to the hard work of library staff and the dedication of faculty, both undergraduate and graduate students at the University of Pennsylvania are given a wide variety of opportunities to use special collections for classes, projects, and independent research, something Garofalo thinks that Fee would find important. “When I found out it would be used for research and education, I thought, ‘that’s Liz. That’s just perfect,” she says. “It was the place for Liz. It was the place for me."

Date

October 13, 2021