University of Pennsylvania Libraries Receives Archive of Writer, Historian, and Activist James G. Spady

Ed. Note: James G. Spady is not related to James Spady, former director of the Fels Center of Government at Penn.

The University of Pennsylvania Libraries is pleased to announce the recent gift of the archive of James G. Spady, a writer, historian, and activist who shed light on understudied aspects of African American history, and whose legacy and intellectual output made him a salient and influential African American figure in his own right. After Spady’s death in 2020 at age 75, his family and a group of Penn alumni whom Spady closely mentored worked to build an archive of his prolific writings, which will now be preserved – and eventually celebrated through exhibitions and events – at Penn.

“My parents and I are thrilled that my uncle's documents will have a home at the Penn Libraries,” says Jeriba Allen, Spady’s niece who facilitated the gift. “He spent his adult life in Philadelphia and made so many connections at the University of Pennsylvania, so it feels kismet that those same connections helped facilitate this gift that will allow his collection to be there for all to explore.”

Spady fostered a strong connection to Penn and in particular to the Van Pelt-Dietrich Library Center, where he regularly conducted research and worked on his books and articles.

“For the collective who helped make this gift happen, the archive is in itself a kind of monument to Spady in the place that he spent so much time thinking and writing,” says Sean Quimby, Associate University Librarian & Director of the Jay I. Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, and Director of the Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies.

Record of a prolific career

According to Spady’s obituary, he “authored or edited more than 15 books, published dozens of scholarly journal articles and book chapters, worked in radio and film, and wrote hundreds of newspaper articles for various print media, particularly historic Black newspapers including the Philadelphia New Observer and Scoop USA.” He received the American Book Awards Lifetime Achievement Award in 1988 at age 45. He interviewed many prominent African American scholars, musicians, and writers, such as James Baldwin, Nina Simone, and Ntozake Shange; he also drew attention to African American cultural figures, intellectuals, and political activists who had been overlooked, such as architect Julian Abele, composer William L. Dawson, and professor, folklorist, poet, and literary critic Sterling A. Brown. As a longtime Philadelphia resident, Spady wrote often about the city and its contributions to the Civil Rights Movement. Later he also documented the history and culture of hip-hop, co-authoring the first-ever trilogy of books on the topic.

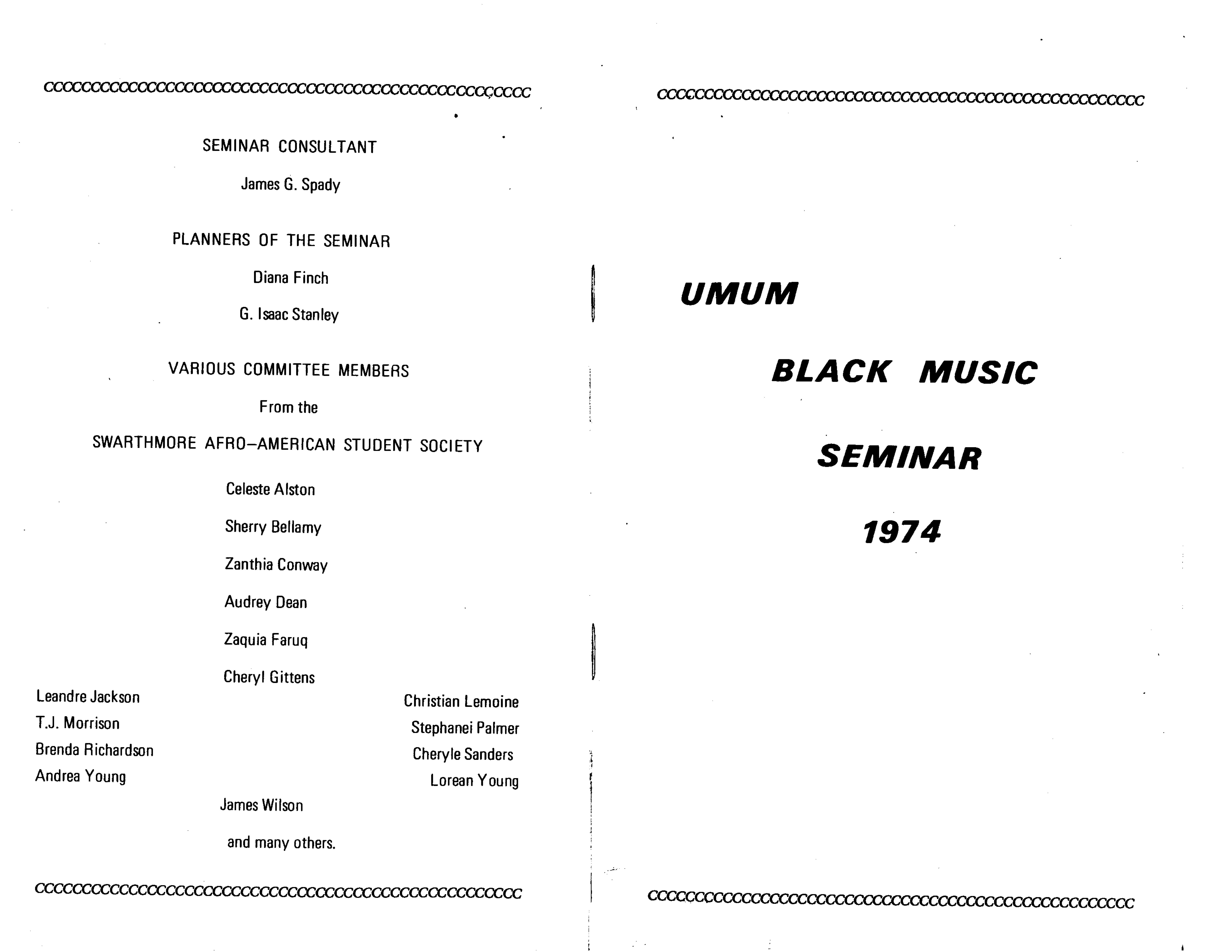

The archive includes rare copies of Spady’s books; copies of the New Observer; research files, correspondence, photographs, and page layouts from his book Georgie Woods – “I'm Only a Man!”: The Life Story of a Mass Communicator, Promoter, Civil Rights Activist (1992) and for an unfinished book on African American architects; photographs taken by Spady’s frequent collaborator Leandre Jackson of many of Spady’s famous interviewees, such as Georgie Woods, Toni Morrison, and Miles Davis. The archive also includes documents relating to the founding of the Black History Museum Library in North Philadelphia of which Spady was the primary founder in 1968 (the museum closed in 1972 after a fire and subsequent theft), as well as documents relating to colloquia Spady organized at Swarthmore College.

According to Samir Meghelli, C’04, a mentee of Spady’s and key participant in the creation of the archive, a standout element of the collection is the archive of the Black History Museum UMUM Newsletter. (UMUM was a term frequently used by Spady that he told others meant “timeless.”)

“First of all, the newsletter title doesn’t do it justice because it really brought together writers from around the country and the world on a range of topics in Black history,” Meghelli says. “It’s just an incredible record of the work that James Spady and his collaborators did in shining a light on really under-explored topics in African American history and culture. You can see the ways that they charted new territory and brought to light historical figures and topics in African American history and culture that in the years since have become much more prominent. They were really doing important work.”

Additionally, some items from Spady’s bookshelf are included. Quimby says, “Because this is kind of an archeological project, the collective feel that these books are important to this intellectual archeology: What is it that Spady was reading? How did it influence him?”

Penn connection

Spady was a fiercely private and happily enigmatic man, so the origin of his relationship to Penn is a bit of a mystery, but Van Pelt was the place where he first crossed paths with many of the students who would become his mentees.

“I met James Spady when I was a sophomore at Penn,” says Meghelli, who is a historian, writer, educator, and serves as a Senior Curator at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. He continues, “I spent a lot of time in what, at the time, was called the fourth-floor Afro-American Seminar Room, as did he, and often surrounded by a pile of books. One day we struck up a conversation and ended up talking for several hours. From that moment forward, we built up a friendship of intellectual exchange and really of mentorship. I remained close to him … for the remainder of his life.” Meghelli and Spady would go on to co-author The Global Cipha: Hip Hop Culture and Consciousness, which was published in 2006.

The Rev. Charles (Chaz) Lattimore Howard, C’00, Penn’s University Chaplain and Vice President for Social Equity & Community, is another mentee of Spady’s. The two happened to meet at a Penn event: “Spady and I were both on a panel, this would have been, 2000, maybe 2001, that some Penn students were hosting on hip-hop. We were both panelists, and Spady kept looking at me,” Howard says. Spady was looking at Howard because his face was familiar to him; in fact, Howard’s grandfather, also named Charles Howard, had once mentored Spady.

“My grandfather was a journalist, also, in New York. He helped James Spady when he was getting started,” Howard says. “I think he was kind of paying it back by mentoring me, when I was in grad school and beginning my career.”

Howard recalls, “The Penn Libraries [particularly Van Pelt] was like his office. Most of the things he wrote over 25 or 30 years of his life were written in Mark’s Café or the Afro-American Seminar Room.”

Champion of Black excellence

Spady also organized many events at Penn, from his own guest lectures to panels to celebrations of published works. Meghelli says that one of these events was among the first of its kind to honor pioneering architect Julian Abele, Ar’1902, the first Black graduate of what is today the School of Design, for designing various buildings on campus, including the President’s House and Irvine Auditorium. Spady also self-published a pamphlet he wrote, “Julian Abele and the Architecture of Bon Vivant,” to raise awareness of Abele’s contribution to Philadelphia as we know it. Today, Abele is known beyond Penn as the designer of the central branch of the Free Library of Philadelphia, Harvard’s flagship library, multiple buildings on Duke’s campus, and much more; his legacy is honored at Penn through a named fellowship fund.

“We’re not talking about Julian Abele the way we are without Spady,” Howard says.

“He was really a pioneer in many ways and in a number of fields, and brought to light a number of forgotten historical figures,” Meghelli says, adding, “He did the same thing with hip-hop when it wasn’t taken seriously as an area of study. ... He was often ahead of the curve, and did a tremendous amount of the work of trying to document historical figures and movements that hadn’t received the kind of scholarly recognition that they deserved.”

Photographer Leandre Jackson closely collaborated with Spady for decades. Jackson published an article about Spady’s methodology in the Western Journal of Black Studies in 2013 which described the environment in which Spady was pioneering “Hiphopography”: “In contrast to what Spady was writing about, some of America's largest media channels, and so-called popular cultural observers, in white and black communities alike viewed hip-hop culture ... in a decidedly hostile manner. Like other black youth cultural and social revolutions ... hip-hop culture was greeted with a heavy dose of stigmatization and suspicion.”

Spady turned this view on its head by treating hip-hop as a form of art and poetry, and taking the people who produced it seriously. With Spady choosing the subjects, he and Jackson conducted interviews and accompanying photographs together for decades. Looking back on their work together, Jackson says, “If he were still here, Spady would tell you that my interest in hip-hop culture was nil at the beginning. We had many conversations in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s about the importance of the culture and creators of hip-hop – especially in Philadelphia. However, it was not until he, I, and others worked on the book Nation Conscious Rap that I began to realize just how important hip-hop was – and is.”

"[Spady’s books] really were the foundational texts of serious scholarship around hip-hop,” Howard says. “He kind of built a field and made it legitimate in a lot of ways. To see him sit with rappers … for him to take their ideas very seriously... was another big impact on what he did for hip-hop."

As a journalist, Spady pioneered a form of writing about hip-hop that used the form’s language. Howard describes this as “literary freedom”: “He kind of intentionally broke grammatical rules, and even … spelling rules. He would write in the vernacular intentionally. He would have long transcriptions in a lot of what he wrote, in the name of conserving the voice of his interlocutor.”

Meghelli was a hip-hop DJ when he met Spady, and quickly discovered a new way to appreciate the genre: “I was just fascinated … that this music and this culture was something that people could apply a scholarly lens to, and actually study and document the history of it,” he says.

Passing the torch

Similarly to the way Spady treated his interviewees, his mentees remember him treating them with the utmost respect as serious scholars.

“I think every student and scholar who engaged him was challenged around intellectual and personal integrity. I think he took those who he sat across from very, very seriously,” Howard says. “To have an older Black man, a serious journalist, take your mind seriously, is wonderfully affirming – in a world where often our intellectual capabilities are often dismissed.”

Spady never placed stock in academic degrees, and instead was constantly learning, teaching, and modeling the life of an independent journalist and intellectual. Meghelli describes him as “one of the most brilliant people I’ve ever crossed paths with,” and Howard says “I don’t think it’s too strong to [call Spady a] genius.”

“He was a free man. He was very proud of his Blackness. And also was unbossed, and unbought,” Howard continues. “Spady was not widely known outside of those who really know – and yet, I think Spady has died with a freedom and a deep integrity when it comes to his scholarship, that I don’t think he would do it differently.”

Meghelli adds, “James Spady helped build an incredible intellectual community... People of all ages are now connected because of James Spady and his mentorship of us over the years. It’s really about the community of people. They made [this donation] possible in support of the family and the family’s wishes.”

Howard and Meghelli, alongside the others who make up this community, are excited to make Spady’s archive available for future research and, much like Spady did for others, bring recognition to his legacy.

Samantha Hill, Curator of Civic Engagement, will lead the preservation of the Spady archive and the curation of exhibits of Spady’s and Jackson’s collaborative work once it has been cataloged.

"Spady’s work brought recognition to those he touched, and now, Penn Libraries and the Spady’s colleagues and mentees are working together to build out his archive through donations to further preserve his legacy," Hill says. "This endeavor to gather representations of Spady’s influential work will also become an essential component of the Spady/Jackson exhibit at the Kislak Center. This collaboration will draw inspiration from Spady’s methodology to highlight his accomplishments and celebrate his impact as a prolific scholar, mentor and friend."

Featured photo at top of page: James Spady (right) interviews South African writer Es'kia Mphahlele. Images provided by Leandre K. Jackson.

Date

March 22, 2023