University of Pennsylvania Libraries Acquires Leandre Jackson Photograph Collection

The images depict scenes in Philadelphia, New York, and Washington, D.C., and many were published in the Philadelphia New Observer Weekly, magazines, scholarly newsletters, and books. Featured photo: "Card Game" by Leandre K. Jackson.

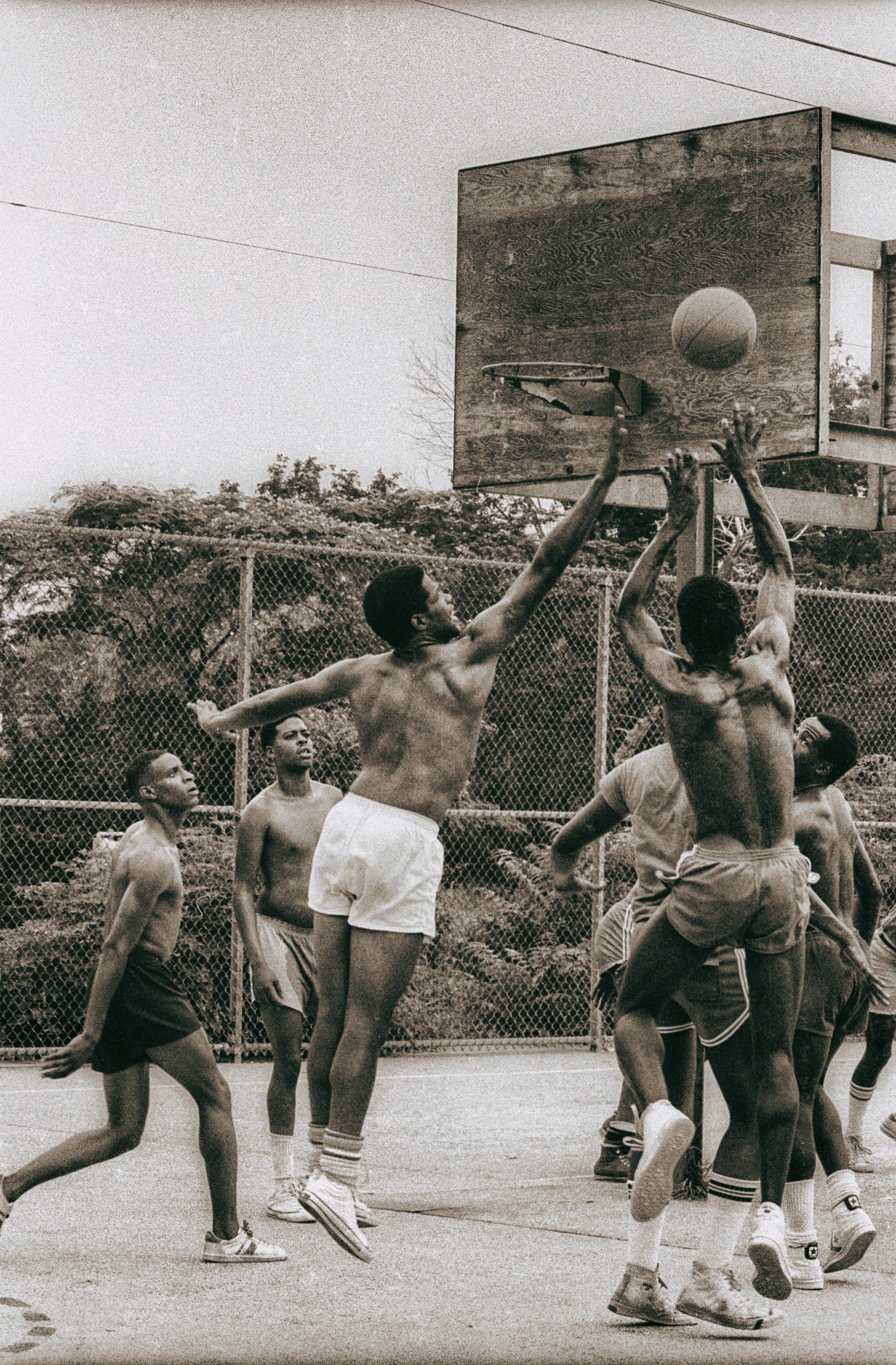

The University of Pennsylvania Libraries has acquired a collection of photographs by Leandre K. Jackson, a photographer known for his vibrant candid shots depicting Black life in Philadelphia and around the world, as well as his striking portraits of eminent Black cultural figures, writers, and musicians. The Penn Libraries will preserve and provide access to the photographs with the expert guidance of Samantha Hill, Curator for Civic Engagement.

“Leandre Jackson’s photography encompasses quintessential moments of life in Philadelphia and beyond,” Hill says. “His subjects, ranging from portraiture to cityscapes, document captivating scenes from the Black experience.”

“We are delighted that Leandre has chosen to place his archive with Penn, where it will be preserved and made accessible both to scholars and the general public, and where it serves to further enhance the civic engagement program that Samantha Hill is developing here,” says Sean Quimby, Associate University Librarian & Director of the Jay I. Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, Director of the Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies.

The photographs acquired by Penn are a product of Jackson’s decades-long collaboration with historian James G. Spady — a partnership that launched Jackson’s career. The images depict scenes in Philadelphia, New York, and Washington, D.C., and many were published in the Philadelphia New Observer Weekly, magazines, scholarly newsletters, and books.

A lifelong passion

Jackson was introduced to photography in 1970, as a high school student. He got to use his first camera, a Nikon F, during the Swarthmore College Summer Studies Program.

“Once I began developing and printing my own black and white negatives, I was hooked,” Jackson says. “By the time I graduated from high school, I had spent numerous hours in darkrooms at Swarthmore College.”

He knew he wanted to be a photographer when he entered his first year of college at Swarthmore, “to the chagrin of my family and friends,” he says. While taking classes in English literature and Black studies, Jackson followed his own curriculum on photography. “During these years I read everything I could and spent hours at night in the darkroom,” he says. “I enlisted fellow students as unpaid models while learning studio lighting, use of props, and other techniques. I read as many books as possible about and by photographers, alongside the many textbooks we were assigned.”

Meanwhile, he became increasingly involved in conferences and symposia on different aspects of Black culture. This is how Jackson met historian and activist James G. Spady, who came to Swarthmore as a consultant for a conference called the UMUM Black Music Seminar. (Spady used the word “UMUM” in the titles of many events and publications, claiming that it meant “timeless.”) Jackson would go on to collaborate with Spady on two more UMUM symposia after graduating from Swarthmore, where he had taken a job as director of the school’s Black Cultural Center while continuing to pursue photography. The symposia brought a number of influential speakers and writers to the campus, among them composer T.J. Anderson, drummer Milford Graves, and poet Sonia Sanchez.

“It was during this period that two major events took place,” Jackson says. “First, I began being published and exhibited; secondly, James and I decided to collaborate going forward.”

A fruitful partnership

The pair’s first journalistic collaboration was a profile of nuclear scientist, mechanical engineer, and mathematician Dr. Jesse Ernest Wilkins, Jr., who at the time had just become the first African American President of the American Nuclear Society. Wilkins had attended the University of Chicago at age 13 and was hailed in national media as “the Negro Genius.”

“This single interview led to almost three decades of work together on newspapers, books, newsletters, magazines, and other media,” Jackson says.

Jackson and Spady were inspired by the partnership between photographer Roy DeCarava and writer Langston Hughes as evidenced in their collaborative work, The Sweet Flypaper of Life, which uniquely brought words and images together to form what writer Sonia Weiner calls “composite modes of expression.” As Jackson explains in an essay for Swarthmore Magazine, “While I was still an undergraduate at Swarthmore College, we would spend hours — on campus and off — discussing creative methods of 'fusing' words and images.”

For each interview, Spady chose and contacted subjects. Then Jackson joined him, often taking candid shots during the interview as well as portraits of the subject. If the subject was a performer, Jackson would often attend a performance to take shots of them exercising their craft. His online gallery displays many of these photographs, and visitors will see plenty of familiar faces as well as plenty of people that they do not recognize.

Explaining their shared philosophy toward the work, Jackson says, “It was always our intent to elevate the stories and history of those being excised from our common history. To do the latter, we knew we had to tell – in words and photographs – the stories of the culture, the well-known and little-known. Thus, alongside the images and interviews of Eartha Kitt, Nina Simone, Dizzy Gillespie, and Pulitzer Prize winner Charles Fuller, are the narratives of Walter Dean Myers, Professor Darlene Clarke Hine, and North Philadelphia bookstore owner Ms. Hilda Bryan.”

Indeed, the pair interviewed and photographed countless prominent African American figures, including many who were culturally and historically significant but not well known. Jackson had developed a preference for portrait photography early in his career: “I have always photographed those around me as generally, people – and their actions – were far more interesting than empty barns, flowers, hallways,” and the like, he says. This preference aided his partnership with Spady, as the written word and photographs together captured the subjects’ personalities and ways of carrying themselves.

“Part of what was so powerful about Leandre’s work and their work together was it was about capturing people in their everyday environment,” says Samir Meghelli, C’04, a mentee of Spady’s who frequently worked with both men. Of their work with prominent figures, Meghelli continues, “I think that was a really key part of the work of both Leandre and James, was humanizing these figures that people often thought of as stars, but to understand them as rooted in a particular context in a particular community or set of communities, in a particular history. I think both Leandre and James’ work did that incredibly well. And since they had worked together for so many years, there obviously was a common understanding of the approach and the desired outcomes.”

Spady also converted Jackson to his own views on hip-hop music, convincing him that it was an art form to be taken seriously. Jackson photographed many hip-hop legends, including Public Enemy, DMX, and Wu-Tang Clan, so his favorite experience from this time may come as a surprise: “My favorite rapper – despite his other career – was Shaquille O’Neal," Jackson says. “He released his debut rap album, Shaq Diesel, in 1993. Despite some critical noise, the album was a success and reached No. 25 on Billboard, becoming platinum in 1994.” (Spady’s interview with Shaq accompanied by Jackson’s photographs is featured in the second volume of Street Conscious Rap and also appeared in the Observer.)

More stories to tell

The Jackson acquisition arrives in tandem with Spady’s archive, which was recently donated by the historian’s family. Once catalogued, both collections will be made available for academic research and showcased together in exhibits and events, allowing viewers to gain further context and insight into each by seeing the ways in which they work together.

"Those connections are deeply intertwined,” says Meghelli.

Another mentee of Spady’s, the Rev. Charles (Chaz) Lattimore Howard, C’00, Penn’s University Chaplain and Vice President for Social Equity & Community, says of Jackson and Spady, “They were a dynamic duo.” Howard is thrilled that Penn will “preserve the legacy of two … I don’t think it’s too strong to say two geniuses.”

Hill is ready to dig into both of these collections and explore the best ways to exhibit them together.

"Jackson and Spady weave together significant elements about their subjects through words and images. Their collaboration is a compelling form of storytelling that allows audiences to engage and discover intriguing details about Black intellectuals and cultural producers,” she says. “The rich content within these two collections performs together in perfect harmony to develop an exhibition full of energy, and excitement that features highlights from Black culture."

Date

June 6, 2023