Introduction to The Typography of Independence

An introduction to The Typography of Independence and the Makers Blog

For most, the Declaration of Independence makes us vaguely recall the words of the document itself (especially the first paragraph, about “all men being created equal”). Or we recall a vinegared facsimile acquired on a school trip to Washington DC or Independence Hall, folded neatly in an envelope.

None of this indicates the passion and expedience with which the original document was produced. In 1776, paper and ink were the not only the fastest way to communicate intention, but also the most authoritative.

Surrounded as we are in 2025 with much more immediate but temporal forms of communication (our phones, computers, tablets) it is important to remember in 1776 there was no electricity; letterpress printing was the only way to print text and there were only about 36 printing presses in the colonies; all type was imported from England; paper was rare and precious; and on top of all of that, 40% the population was illiterate. Because of all of this, printed documents held an authority in the 18th century that they do not hold today.

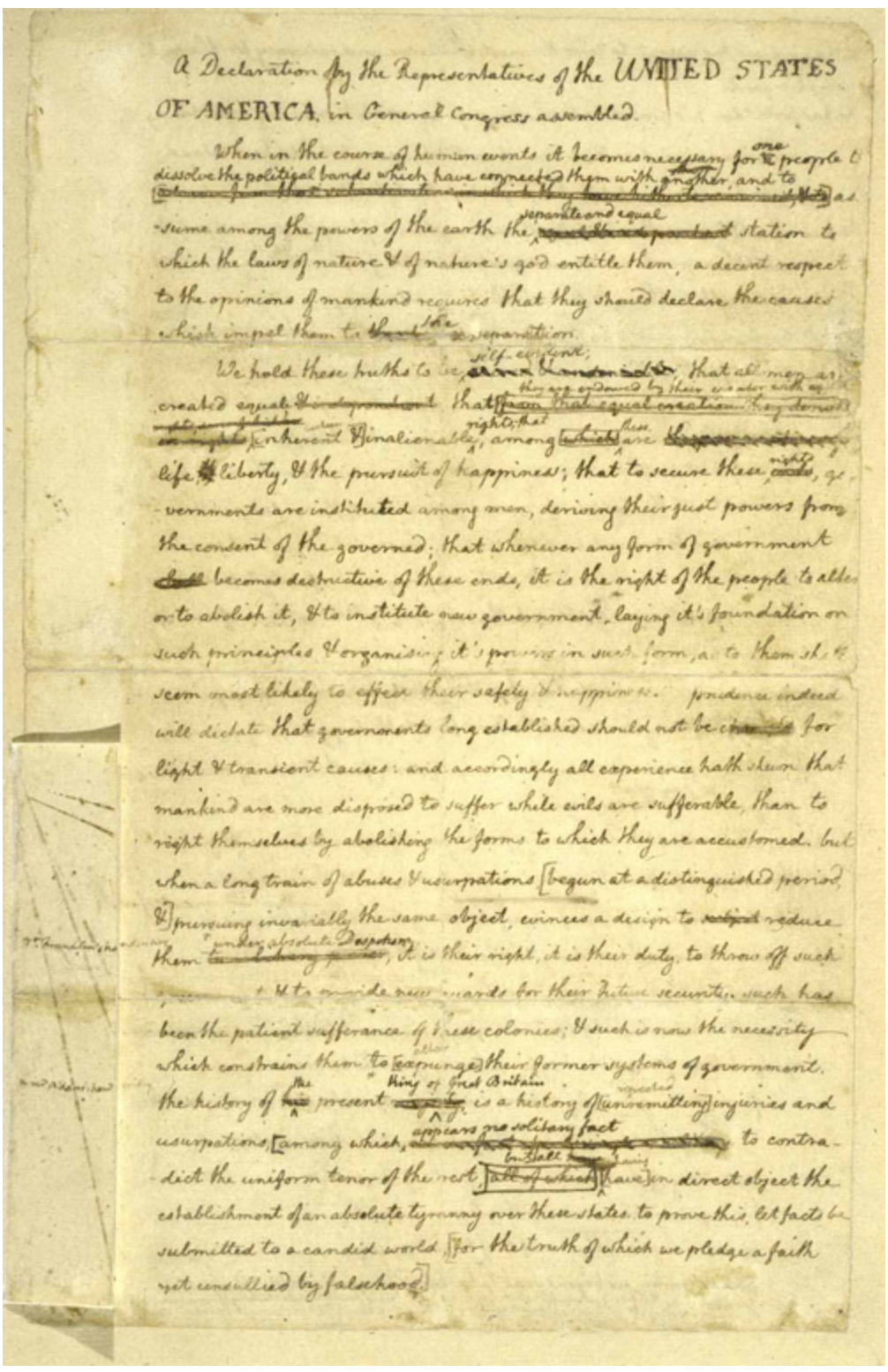

In the summer of 1776, the delegates knew that they needed to agree upon and release a formal written statement announcing the colonies’ self-governance and independence from Britain. Jefferson wrote out the last of a few final drafts, and then placed the document on a table in Independence Hall for commentary by the delegates.

On July 4 the approved draft was taken to John Dunlap’s printshop on Market Street in Philadelphia, where, within 12 hours, it was composed in metal type, printed and released to the world as a single sheet broadside meant to be posted, folded, carried, read aloud. Here is a good imagined description of that printing.

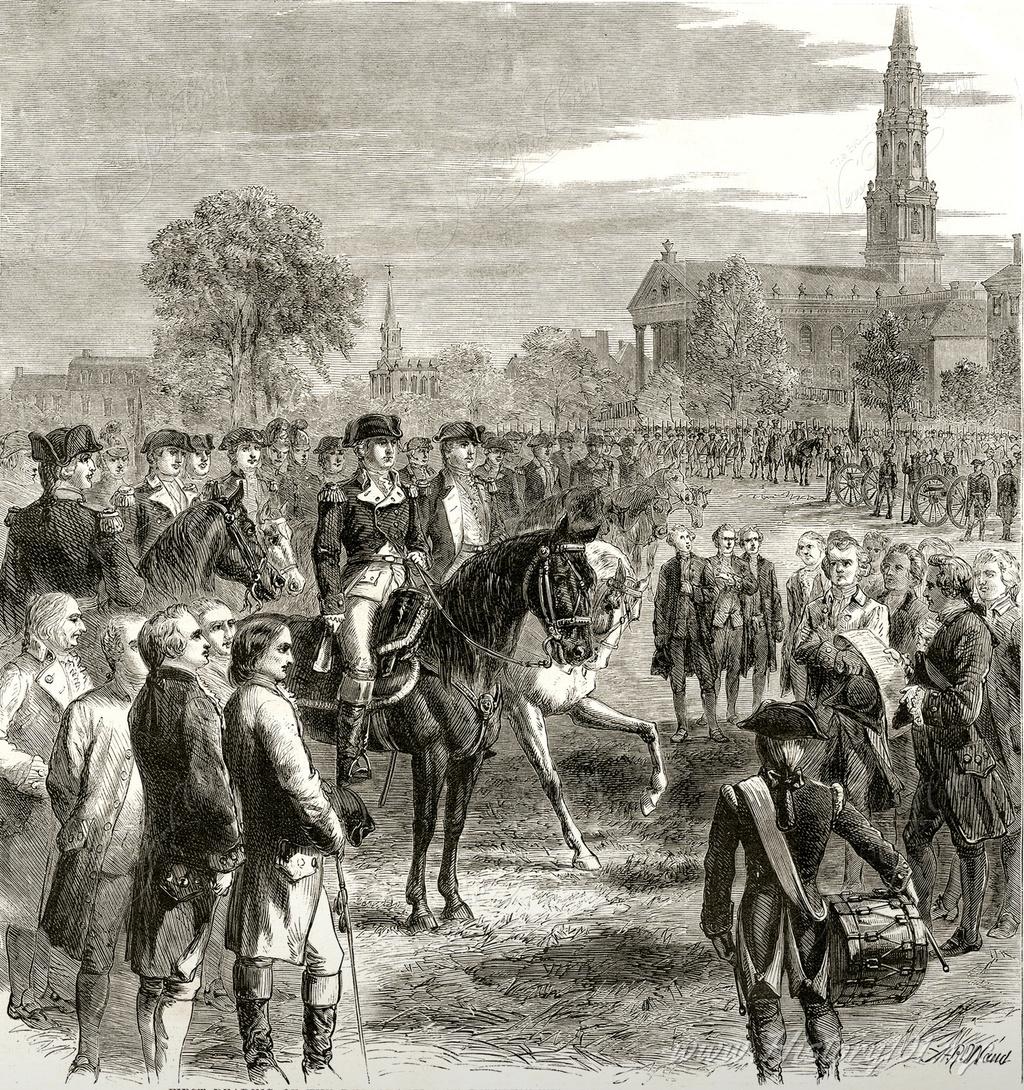

Public readings of the Declaration began immediately on July 4, the first in Philadelphia. General Washington waited in Lower Manhattan to receive a copy to read aloud to the gathered audience.

At the time, it was not Jefferson’s flowery and inaccurate language about all men being created equal that was the most interesting and scandalous to the world, but the last paragraph, “That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do.”

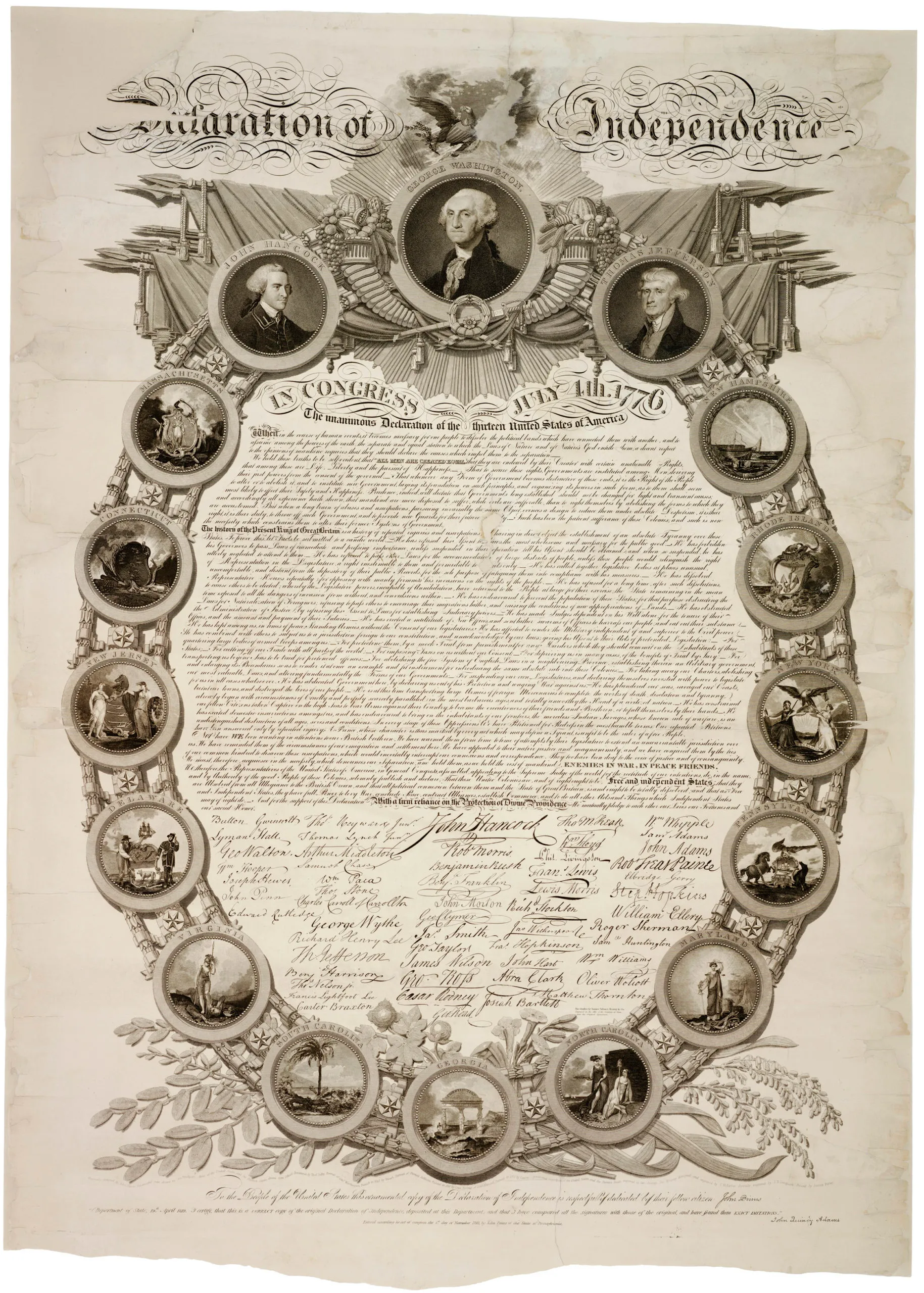

The release of the Dunlap broadside kickstarted an American past-time which we as a population have forgotten in our digital age: the endless reproduction of the Declaration as a document. John Bodwell describes this history in his book The Declaration in Script and Print. A favorite is the 1891 Binn broadside, a both masterful and campy engraving, which was the first facsimile to be marketed and sold as a work of art.

The Common Press joins this tradition of investing much human and material capital into making a facsimile of the Declaration. Starting in September 2025, we will spend a year exploring the materiality of the Declaration and the craft practices that created this document in 1776. We will collect cotton and linen rags from the streets of Philadelphia and make them into paper pulp. We will use the paper pulp to pull sheets of paper at the papermill at Historic Rittenhouse Town, the first papermill in the colonies. We will set Caslon type cast especially for this project to form the body of text that makes up the Declaration. We will print this forme on our 1889 cast-iron handpress, the oldest in our printshop.

This blog will serve as an evolving documentation of the project.

Thank you to project sponsors: the Philadelphia Funder Collaborative for the Semiquincentennial, The Sachs Programs for Arts Innovation, and Penn Libraries. Thanks to Emily Sneff, Kathryn Reuter, Erica Honson, and Jessica Peterson for ideation, research and design.