Printing and Type in the Revolutionary Era

A brief history of the Dunlap broadside and the Caslon type that was used to print it, for the Uncovered Narratives #1: Printing and Type in the Revolutionary era.

Printing and Type in the Revolutionary-Era

On the afternoon of July 4, 1776, the delegates of the Continental Congress issued a command:

That the committee appointed to prepare the declaration, superintend and correct the press.That copies of the declaration be sent to the several assemblies, conventions and committees, or councils of safety, and to the several commanding officers of the continental troops; that it be proclaimed in each of the United States, at the head of the army. (Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, 516)

John Dunlap, in whose printing shop the first edition of the Declaration was printed, probably received the fair copy of declaration text in Thomas Jefferson’s handwriting on the evening of July 4. This original document and its delivery have been lost to history, but scholars like to imagine that Jefferson, Adams and/or Franklin delivered the text to the printshop.

The haste with which the first edition of the Declaration was printed in 1776 contrasts with the significance of the surviving 26 copies in 2025. In his book The John Dunlap Broadside: The First Printing of the Declaration of Independence, Frederick R. Goff compares the exant copies and finds errors that were corrected throughout the first print run: the forme is printed slanted in some copies (indicating a hasty lock-up), there are broken letters, and missing words are corrected during the process of printing.

As a printer, reading about these mistakes makes me shake my head in sympathy with Dunlap and his printers and compositors. Imagine having the members of the Continental Congress (including famous printer Franklin) waiting impatiently for a print of the document they had spent days arguing over, while setting small 12-point type in candlelight throughout the night. The mistakes that Goff lists are no doubt the result of haste, exhaustion, and the lack of strong lighting. John Dunlap was known to be a careful and good printer; another printer of the era commented: “Dunlap executed his printing in a neat and correct manner” (quoted in “John Dunlap” Dictionary of American Biography, 515).

There is no record of how many copies of the Declaration were printed that night, but it is evident that John Dunlap used all the paper that was available to him. The existing copies have a range of different watermarks and sources. Goff mentions an account of Hanock imploring Dunlap to print more copies in the days after July 4. There is offset ink on the existing copies, indicating the prints were printed and folded before they were completely dry: the Declaration must be distributed and declared!

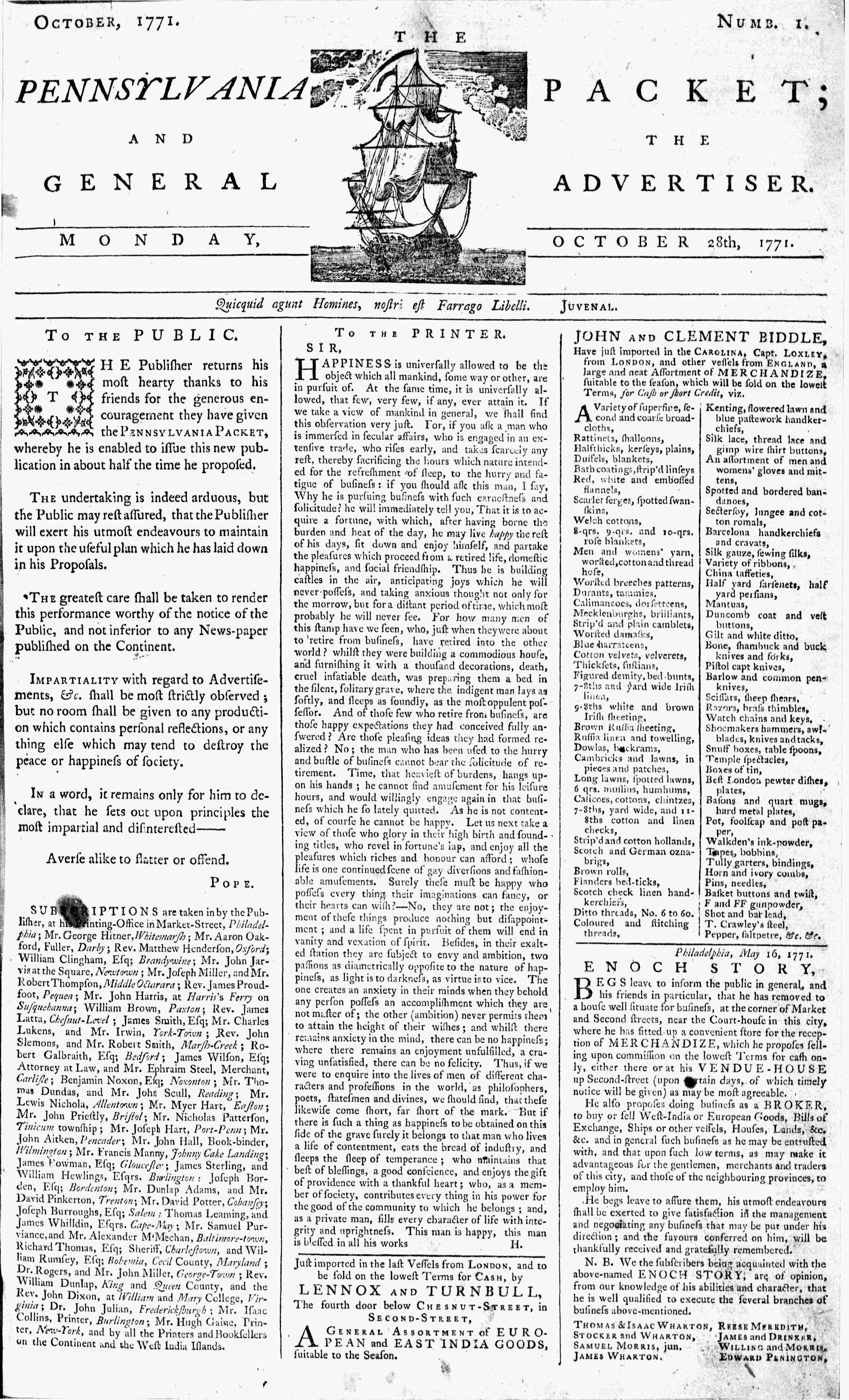

John Dunlap immigrated from Ireland at the age of 10 to work as a printer’s apprentice to his uncle: William Dunlap. William Dunlap was married to the niece of Deborah Franklin, Benjamin Franklin’s common law wife. In 1768, at the age of 22, John Dunlap purchased his uncle’s printshop and opened his own printshop close to Independence Hall. John had made a name for himself as the publisher of the Pennsylvania Packet and the General Advertiser, the first successful daily newspaper in the United States (“John Dunlap,” in Encyclopedia of the Continental Congresses, 334-337).

The Declaration is set in Caslon type. In the eighteenth century, font choice was limited to say the least. Typographers (type designers) were still perfecting the typecasting process as they explored ideal shapes for printing roman characters on a variety of paper types. Their designs were regional and nationalist, so British printers preferred to use Dutch type instead of French type (even though Garamond was the best design at the time). In the colonies, there was no type foundry, so all type was shipped across the ocean.

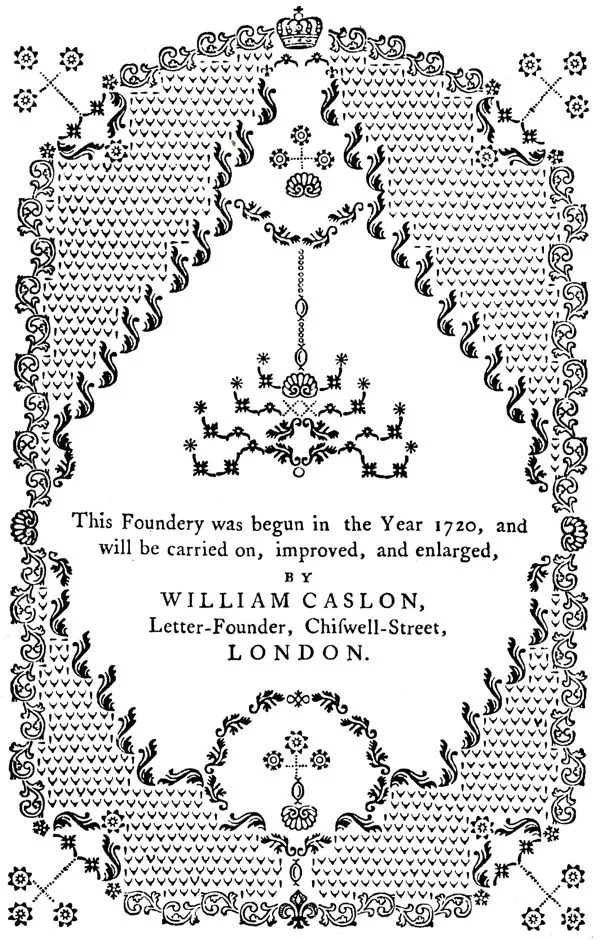

William Caslon released his font in 1739, and “rescue(d) his country from the disgrace of typographical inferiority” (Hansard 1825, 348). Finally, there was a refined and beautiful font designed by an English speaker to print English.

Quickly, William Caslon’s typeface exploded in popularity. The typeface Caslon became so ubiquitous that printers coined the phrase "when in doubt, use Caslon". William Caslon became the official type caster for the king and cast a set of type specifically for King George.

Benjamin Franklin was a printers’ apprentice in London at the same time Caslon’s type was emerging. There is little doubt that Franklin must have met Caslon. Franklin later corresponded with many British type designers, including William Caslon III and Baskerville. (https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-30-02-0490 / https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-09-02-0085)

Benjamin Franklin was the first to use Caslon type in the United States. In 1759, he wrote a letter to his printshop foreman mentioning that he purchased the font (https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-08-02-0086#BNFN-01-08-02-0086-fn-0002). Is it possible Franklin’s Caslon type was used in Dunlap’s shop to print the Declaration? In any case, one can imagine Franklin’s glee having the words from the Declaration: “A Prince, whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people” being set and printed in King George’s favorite typeface.

About the Broadside

In our Open Studio session this month, we will print the following text on a broadside:

Quidquid agunt homines, votum timor ira voluptas gaudia discursus, nostri farrago libelli est — "whatever men get up to, the making of vows, fear, anger, pleasure, joys, business, is the motley subject of our little book."

Phillip Mallett, "Foreward", Forum for Modern Language Studies, Volume XXX, Issue 4, October 1994, Pages 289–292, https://doi.org/10.1093/fmls/XXX.4.289

This sentence—translated as "whatever men get up to, the making of vows, fear, anger, pleasure, joys, business, is the motley subject of our little book" (Mallett 1994, 289)—is an excerpt from Roman poet Juvenal's Satires. John Dunlap used an abbreviation of this text on the masthead of several issues of his newspaper The Pennsylvania Packet.

There is so much we learn from looking at old newspapers… not only the news of the day, but letters to the editor, and advertisements for material goods like candles, coffee, and lamp oil. However, we cannot possible learn all of “whatever men do” from these sources. Innumerable people throughout history, of course, have been intentionally marginalized in their societies and their experiences were not faithfully recorded. In addition, the everyday stuff of life: the sights, smells, and emotions of any given time period can be difficult to understand. Quotidian elements are at once both commonplace and too complex for easy description. As a result, clear details about material history and cultural history can be sparse in the historical record. What did people eat, how did people think, and what did people feel in the past? While we can glimpse what the 1970s were like from photographs and video, the 1770s are much more remote.

Material history and "history from below" form the basis of our Typography of Independence project. Through this series, we are trying to understand the material conditions of the printing of the Declaration of Independence and along the way, shine a light on lesser-known people, places, and processes in history.

Sources:

Caslon, William. 1785. A Specimen of Printing Types: by William Caslon, letter-founder to His Majesty. Galabin and Baker.

Continental Congress. 1906. Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789. Edited by Worthington C. Ford et al. Vol. 5. Government Printing Office.

Goff, Frederick R. 1976. The John Dunlap Broadside: The First Printing of the Declaration of Independence. Library of Congress

Hansard, Thomas Curson. 1825. Typographia: An Historical Sketch of the Origin and Progress of the Art of Printing. Balwin, Cradock, and Joy.

“John Dunlap.” In Dictionary of American Biography. 1930. Edited by Allen Johnson and Dumas Malone. C. Scribner’s Sons. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.163970/page/n523/mode/2up

“John Dunlap.” In Encyclopedia of the Continental Congresses. 2014. Edited by Mark Grossman. Grey House Publishing.

Mallett, Phillip. 1994. "Foreword." Forum for Modern Language Studies 30 (4): 289–292. https://doi.org/10.1093/fmls/XXX.4.289