Spreading News During Revolutionary Times

Emily Sneff, Ph.D., is an early American historian and leading expert on the Declaration of Independence. She is a consulting curator for exhibitions marking the 250th anniversary of the Declaration and the author of the forthcoming book, When the Declaration of Independence Was News (Oxford University Press, April 2026).

In January 1775, three newspapers launched in Philadelphia. Each of these printers promised to preserve the liberty of the press. The proposals for these newspapers show the opportunities and challenges of sharing information during the tumult of the Revolutionary War.

The city’s newspaper business had begun in 1719 with the American Weekly Mercury. Like Boston, the site of the first newspapers in British North America, Philadelphia was a busy port, and printers could rely on ships bringing in a regular supply of information—as well as goods—from other places. Printers also gathered news from letters and other newspapers that arrived by the post. Every week, they would pull information from these diverse sources into the columns of their newspapers, organized from the places at the furthest distance, typically the capitals of Europe, to the colonies and, finally, the most local. It took time for news to travel from other places which meant that, in any given newspaper, there could be information dated weeks if not months earlier. The essays commenting on current events and advertisements that printers relied on to support their businesses were arranged around these paragraphs of news. Some printers chose titles for their newspapers that referenced how information traveled, from the Post to the Packet in reference to mail boats, to the Mercury, the Roman messenger god.

By the fall of 1774, when Philadelphia hosted the First Continental Congress, the city boasted a number of newspapers, including Benjamin Franklin’s former enterprise, the Pennsylvania Gazette, as well as the Pennsylvania Journal, John Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet, and the Staatsbote for German readers. When important intelligence or proclamations needed to be distributed in between their weekly issues, the printers of these newspapers could create supplemental pages or handbills. As tensions between Great Britain and the colonies escalated, printers looked for new opportunities to reach their audiences with the freshest intelligence.

Assessing this media landscape, Benjamin Towne proposed an evening newspaper that would be published in Philadelphia three times per week, on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays, “upon the Forenoon of which Days the Eastern Post arrived (if not prevented by the Weather).”[i] This publication plan was designed to “give particular Satisfaction to all Persons anxious for early Intelligence at this important Crisis.” Towne recognized a need for more timely printed news. He also saw that none of the active newspapers in Philadelphia were published between Wednesday and Saturday, creating a conspicuous communication gap—not only for news, but for advertisements, as well.

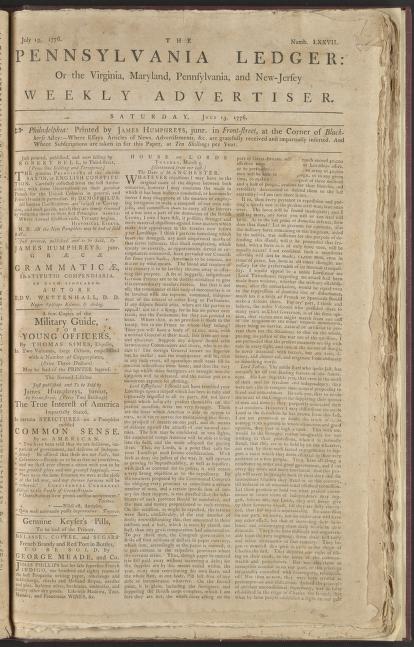

Meanwhile, James Humphreys, Jr. began printing the Pennsylvania Ledger, Or the Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, & New-Jersey Weekly Advertiser on Saturdays. The Ledger was designed “both to amuse and instruct.”[ii] In his proposals, Humphreys gave assurances that the newspaper would be “open to All, and influenced by None.” Within a week of publishing his proposals, he had to double down. Humphreys said that there was “no truth” to the report spreading through the city that he had silent partners in his paper.[iii] In fact, he rejected such a proposal, “being determined to act on the most impartial principles, and not render himself liable to be influenced by any party whatever.”

The third newspaper venture proposed in January 1775 took time to appear before the public. Enoch Story and Daniel Humphreys—who clarified in their proposals that he was the “son of Joshua,” perhaps to distinguish himself from his competitor—made plans for another weekly newspaper, called the Pennsylvania Mercury, and Universal Advertiser. Whether intentional or not, the title referenced the city’s first newspaper more than fifty years earlier. In their first issue on Friday, April 7, Story and Humphreys pointed out that both the type and the paper that they were using were made in America. Although the product might appear “inferior” to newspapers that relied on European imports, Story and Humphreys trusted that “the rustic manufactures of America will prove more grateful to the patriot eye.”[iv] Their newspaper met a hasty end nine months later when their printing office—including all of their American-made paper and type—went up in flames on New Year’s Eve. They issued advertisements in their competitors’ newspapers to round up the outstanding payments from their subscribers. By July 1, 1776, when the Second Continental Congress was sitting down to debate whether to declare independence, Story and Humphreys were still trying to collect their debts, to “compensate for the loss they have sustained, by their printing-office and materials being totally consumed by fire.”[v]

In July 1776, the Declaration of Independence was printed in each of the active newspapers in the United States, beginning in Philadelphia. Benjamin Towne’s triweekly publication plan worked to his advantage, as he was able to publish the news that the Continental Congress had declared independence from Great Britain on July 2 and then, on July 6, the Declaration itself. He was the first newspaper printer to do so. The other newspapers in the city followed: the Pennsylvania Packet on July 8, the Staatsbote on July 9, the Pennsylvania Gazette and the Pennsylvania Journal on July 10, and finally, a full week after Towne’s Pennsylvania Evening Post, the Pennsylvania Ledger on July 13. James Humphreys, Jr.’s later actions show that he printed the Declaration because it was important news, and not because he was particularly excited about it. He ceased publication of the Ledger in November 1776 and resumed in October 1777 after British forces took control of Philadelphia. He took the opportunity to print resolutions from the king’s commissioners, a scathing account of the “rebels” being defeated in the Philadelphia campaign, and an earnest request to his “former customers” who might be interested in renewing their subscriptions.[vi] When the British evacuated Philadelphia the following spring, Humphreys’s paper stopped once again. Benjamin Towne, who also stayed in the city during the British occupation, tried to continue his business and was labeled a traitor.

The experiences of these men highlight the responsibilities of disseminating news during changing times. Printers curated the content of their newspapers. They made business decisions, from the title of their paper to the publication day, in hopes of securing an audience and supplying them with the latest information. Not every newspaper that was in print at the beginning of the Revolutionary War survived the conflict.[vii] A growing city like Philadelphia created opportunities for more readers, but also risks, from fire to military occupation. Newspapers are one of the best sources of information for historians—not only for their contents, but for the clues they provide about the contexts in which they were produced.

[i] Pennsylvania Evening Post, January 24, 1776, p. 1.

[ii] James Humphreys, Jr., “Proposals, For Printing by Subscription, A Free and Impartial Weekly News Paper, To be entitled—The Pennsylvania Ledger, Or the Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New-Jersey Weekly Advertiser…,” January 2, 1775.

[iii] Pennsylvania Gazette, January 11, 1775, p. 1.

[iv] Pennsylvania Mercury, April 7, 1775, p. 1.

[v] Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet, July 1, 1776, p. 3.

[vi] Pennsylvania Ledger, October 10, 1777, pp. 1–2.

[vii] Robert G. Parkinson, The Common Cause: Creating Race and Nation in the American Revolution (Williamsburg and Chapel Hill: Published for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture by the University of North Carolina Press, 2016), p. 675