The Yiddish language has a thousand-year history. However, the Yiddish song is relatively young, developing roughly from the eighteenth century through the first five decades of the twentieth century. It encompasses lullabies and children's songs, love and marriage, humor and satire, dance songs and khasidic melodies, songs of migration, and songs of literary origin, from the concert and art song stage, as well as songs of World War II, written and sung in the camps and ghettos. As aptly put by Alan Lomax, the cultural anthropologist and folk song collector, "As a people live, so do they sing."

Joel Colman, in his master's thesis for a Sacred Music Degree from the Hebrew Union College/Jewish Institute of Religion, on characterizing the purposes of the language, wrote:

The Yiddish language served many different purposes. On the simplest level, it was used by Jews as a means of communication, whether to speak to each other or for "just getting around" heavily Jewishly-populated areas. Yiddish also was a way for Jews to identify as Jews, both personally and intellectually - almost like a badge of honor. For new immigrants with few material possessions, but a strong sense of ethnicity, speaking Yiddish reinforced that identity and even, for some their self-esteem. Once established in America, continuing to speak Yiddish was a sign of taking pride in one's ancestry and in the Jewish community, both past and present. Additionally, the Yiddish language was a tool of unity for those American Jews who shared similar social problems.

Ruth Rubin, Yiddish folk songs collector and author of Voices of a People (McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1973) observed that the Yiddish folk song ". . .is the youngest offspring of Yiddish folk music and one of the richest stores of popular music in modern times. . . it reflects vividly the life of a community of many millions over a period of many generations... These are the songs which served the needs, moods, creative impulses and purposes of a particular environment at particular periods in the history of the largest Jewish community of modern times."

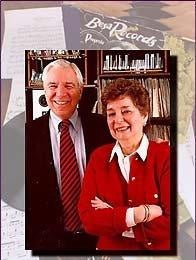

But by the time Bob and Molly Freedman began to collect Yiddish music in the late 1950s, the violent destruction of vast numbers of carriers of Yiddish culture, coupled with the assimilatory process, weakened and sapped the vitality of Yiddish creative forces, and there were relatively few contemporary Yiddish recordings at that time. However, Yiddish, and particularly the music associated with it, has experienced a resurgence.

Maurice Samuel, in his 1971 book, In Praise of Yiddish (Cowles Book Company, Inc., New York), wrote that "a generation ago it was fashionable among modernized Jews to pretend not to understand Yiddish; today it is the fashion to make unfounded claims to a knowledge of it." Yiddish and the music associated with it now seems to have captured the interest of a younger generation, and countless numbers of CDs have and are being produced and issued by contemporary artists and performers on several continents. It is a phenomenon that delights the Freedmans and gives added significance to their precious gift to the University of Pennsylvania.