Behind the Scenes: Curators Reflect on 'Making the Renaissance Manuscript' and 'Medieval Life'

“Ever since starting at Penn, I’ve dreamed about exhibiting some of the Philadelphia region’s lesser-known treasures to a broad audience,” says Nicholas Herman, Curator of Manuscripts for the Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies (SIMS). “Curators dream about such things.”

Herman’s dream will be made manifest this February when Making the Renaissance Manuscript: Discoveries from Philadelphia Libraries opens in the Goldstein Family Gallery on the sixth floor of the Van Pelt-Dietrich Library Center.

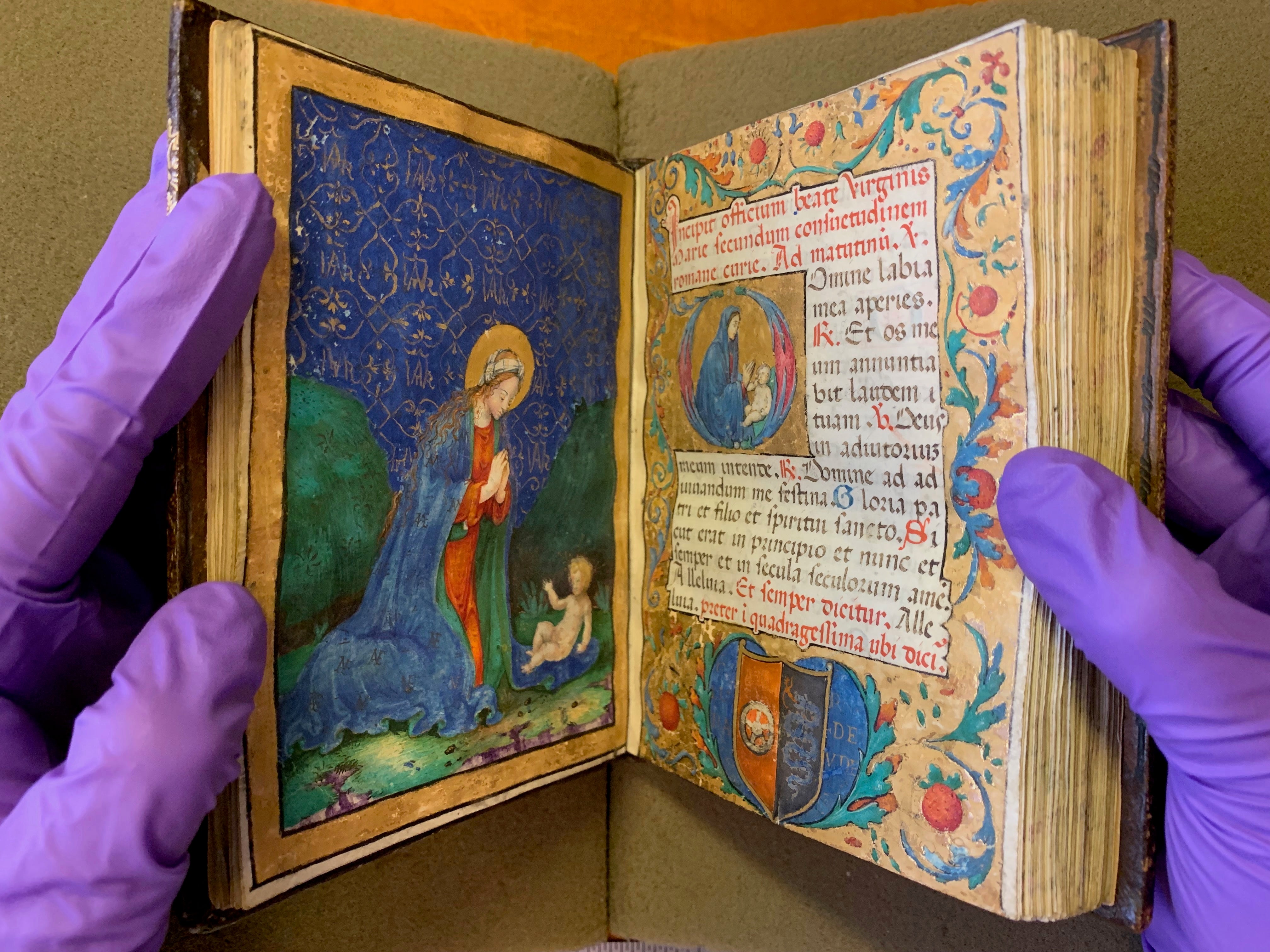

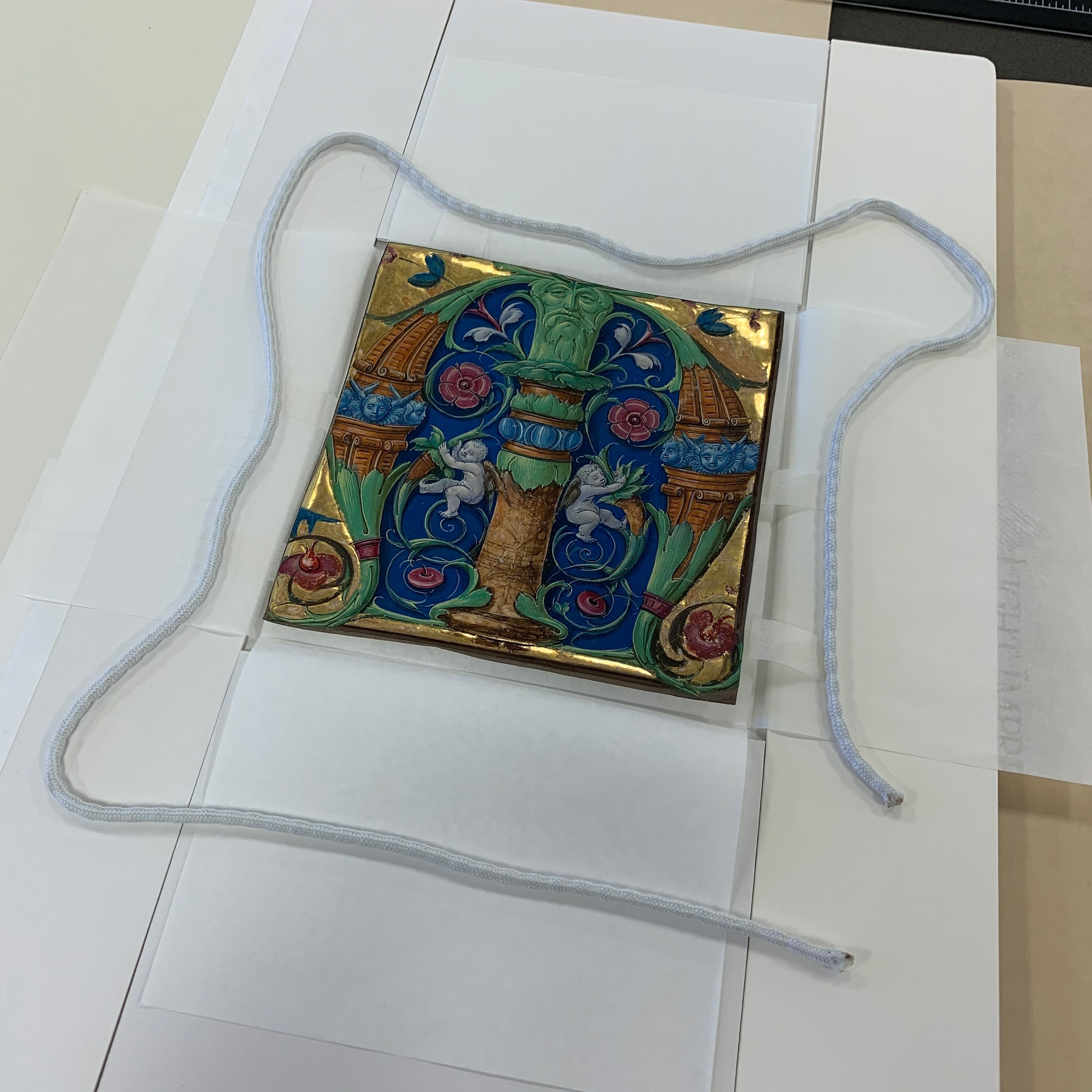

The exhibit, which runs through May 19, features manuscripts, cuttings, and incunables dating from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. “The manuscripts presented in this exhibition extend far beyond the rarefied atmosphere of the Renaissance studiolo,” explains Herman, noting that Making the Renaissance Manuscript gives precedent to “everyday” documents over more elaborate texts.

Most of the nearly 90 objects to be displayed — half of which are on loan to Penn from other Philadelphia-area institutions — have neither been exhibited nor extensively studied before now. Herman, who also teaches in Penn’s History of Art Department and is a Fellow at Harvard’s Villa I Tatti this semester, has produced a fully illustrated catalog of the exhibit to provide scholarly and historical context for each of the featured artifacts.

By both design and good fortune, Making the Renaissance Manuscript coincides with the Renaissance Society of America’s annual conference, which is scheduled to be held in Philadelphia for the first time since 1986.

Making the Renaissance Manuscript is also fortuitously concurrent with an exhibition at the Parkway Central branch of the Free Library of Philadelphia. Medieval Life will be curated by Herman’s colleague in SIMS, Dot Porter, and will run from March 30 through July 25.

“The question that Medieval Life will explore is, ‘How did people in the medieval period think about their world?’ ” says Porter, who is SIMS’ Curator of Digital Research Services and host of Manuscript Monday.

Both Making the Renaissance Manuscript and Medieval Life stem from the Bibliotheca Philadelphiensis (BiblioPhilly) project, the joint effort of fifteen regional libraries to digitize and make freely available 160,000 pages of European medieval and early modern codices. BiblioPhilly constitutes the largest regional online collection of medieval manuscripts in the United States, all available via OPenn, Penn’s open-access database.

Porter’s Medieval Life exhibit will bring together a fascinating miscellany of artifacts — including a production prop from The Jim Henson Company’s The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance (see below) — to approximate a Middle-Age worldview. As Porter and her co-collaborators at the Free Library explain, “This exhibit will examine the many and varied ways that medieval life reflects our own in regard to topics like work, faith, the natural world, justice, and family.”

Below, Herman and Porter discuss their respective exhibits and their involvement with BiblioPhilly.

Nick Herman, Curator of Making the Renaissance Manuscript

Making the Renaissance Manuscript came about through three complementary circumstances. Firstly, the spring 2020 timeslot in the Goldstein Family Gallery, our state-of-the-art, climate-controlled exhibition space at the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, became available.

I then realized that this exhibition period would coincide with the annual conference of the Renaissance Society of America in Philadelphia in early April 2020. The RSA is one of America’s truly venerable scholarly societies, and its annual meetings typically draw around 3,000 attendees. This would be a golden opportunity to present an exhibition to a captive audience who might then be able to spread the word about Philadelphia’s glorious constellation of material related to Renaissance book history.

The most significant circumstance that enabled the exhibition, however, was the successful conclusion of the BiblioPhilly initiative in 2019. Over the preceding three years, this collaborative project digitized, described, and made available online nearly 500 medieval and early modern manuscripts held at fifteen different local institutions. This happy endeavor, led jointly by the University of Pennsylvania, the Free Library of Philadelphia, and Lehigh University, was enabled by a generous grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources.

Dot Porter was a co-PI for the project. She and I, together with our manuscript cataloguing librarian, Amey Hutchins, were the principle catalogers for the project. We were assisted by Erin Connelly, our former CLIR Postdoctoral Fellow for Data Curation in Medieval Studies, Penn Comparative Literature graduate student Judith Weston, and visiting intern Oliver Mitchell from the Courtauld Institute of Art in London.

Over the course of the BiblioPhilly project, numerous fascinating discoveries were made, and I became eager to share these through an exhibition. In the meantime, I have been authoring a year-long series of weekly blog posts entitled 52 Discoveries from the Bibliotheca Philadelphiensis Project, and this has provided a preview of some of the exhibition material.

For Making the Renaissance Manuscript, because we wanted to encompass the broadest possible range of ideas and material manifestations associated with this period in Europe, it became clear that a loan exhibition would be necessary. While Penn has a significant collection of European manuscripts from the fourteenth through to the sixteenth centuries, including the amazing Lawrence J. Schoenberg Collection, the gaps in our collection (notably in lavish prayer books, liturgical volumes, and fine humanist copies of classical texts) meant that the full narrative of Renaissance culture and thought could only be partially represented by items held at the Kislak Center.

By bringing things together from our sister institutions temporarily under one roof, we could offer a richer panorama. Identifying and securing these loans from a wide range of sister institutions was a rewarding challenge. Because of logistical constraints, we weren’t able to include every BiblioPhilly institution, and indeed we reached out to include a book from La Salle University, which wasn’t officially part of the project, as well as to a private collector, to further enrich the scope of objects on display.

In the end, we have loans from Bryn Mawr College, the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, the Free Library of Philadelphia, Lehigh University, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Temple University, and the Rosenbach Museum and Library, in addition to those just mentioned from La Salle and a private collector. About half of the 88 items are loans, while the other half hail from Penn’s own holdings.

By lucky coincidence, one of our major partners in the project and the region’s foremost repository of illuminated manuscripts, the Free Library of Philadelphia, will be holding a complementary exhibition at their Parkway Central location. Curated by Dot Porter and entitled Medieval Life, this display will provide the public with an introductory overview of the medieval manuscript book and its relation to present-day questions of identity, politics, and expression.

All told, during the spring of 2020, amateurs and specialists alike will be able to learn a great deal about the pre-modern book through these two extraordinary events.

Dot Porter, Curator of Medieval Life

Both Making the Renaissance Manuscript and Medieval Life are fruits of the BiblioPhilly project. Nick Herman's exhibition is really focused on the scholarly side of things, talking about discoveries that were made over the three years of the project. Medieval Life, on the other hand, given its location in the Parkway Central location of the Free Library of Philadelphia, is aimed at a general audience and focuses on bringing the medieval world closer to the modern one. I’m so excited to be able to bring the rich medieval and Renaissance manuscript collections of the Philadelphia area to an audience that might not otherwise have the opportunity or interest to learn about them.

My own path to Medieval Live comes straight through the BiblioPhilly manuscript digitization project. As a co-PI on the project who was primarily responsible for logistics and cataloging, I worked closely with the Free Library of Philadelphia over the three years of the project. 250 of the codices included in the project are held at the Free Library, so there was a lot of logistical work involved with bringing the manuscripts to Penn for photography. Catalogers on the project also went to the Free Library to complete some of their work.

In addition to the codices, the Free Library also has a very large collection of manuscript leaves and cuttings (which are illuminations and letters cut out of manuscripts and pasted onto board). Although they had already been photographed previously, we incorporated them into the final project as well. So I worked with the Free Library in getting access to those digital images and the cataloging data that was already available.

Many of these manuscripts (the ones that aren’t in Nick’s exhibit, of course) will be included in Medieval Life. The exhibition has around 80 manuscripts from five European countries, in Latin, English, French, Arabic, and Hebrew, dating from the twelfth through the sixteenth century, so it represents quite a range of material. In addition to exploring how medieval people thought about their world, the exhibition will also include snapshots of how modern people think about their world in comparison, and how we still value medieval manuscripts in popular culture today.

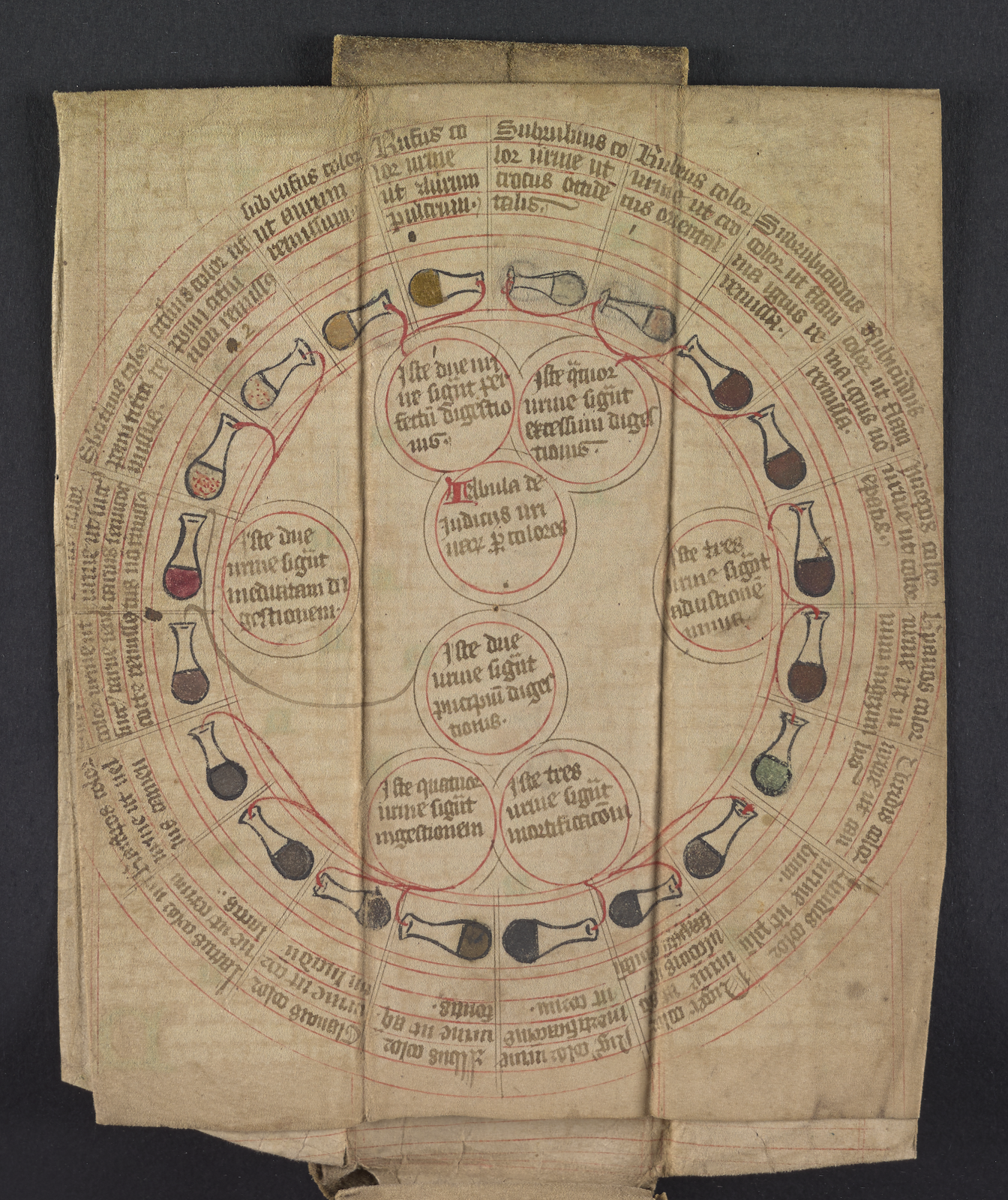

Here’s one of the images that will be featured in Medieval Life, and it neatly demonstrates the medieval-modern connection we’re aiming for. It’s a urine wheel, from Rosenbach MS 1004/29, fol 9C. These were used to diagnose diseases: a doctor would collect urine in a clear glass flask and compare the color, scent, and so forth to the wheels. It’s pretty similar to getting your pee tested at the doctor today!

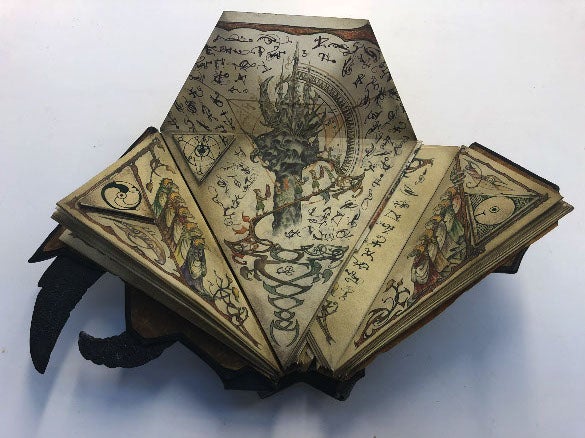

Perhaps the most broadly compelling of the items that will be on display, however, is the one that had nothing to do with BiblioPhilly: The Free Library of Philadelphia has been loaned a production prop of the Skeksis Book of Law, as seen in the television reboot of The Dark Crystal, courtesy of The Jim Henson Company and Netflix. The Skeksis Book of Law, adorned with the symbol of aggression, codified the alliance between the Skeksis and the Gelfling, endorsing the Skeksis' primacy to the detriment of the Gelfling. In the show, the Vapran princess Brea reads about the Skeksis tithing ceremony in the great library of Ha’rar. Graphic designer Philippa Broadhurst created the interior using a Skeksis language alphabet devised by the conceptual designer for The Dark Crystal film and series, Brian Froud. Richard Roberts (Set Decorator), Gavin Bocquet (Production Designer), and Ty Teiger (Prop Master) designed and built the prop with input from Cameron Richardson (associate producer).

It was important for me that we include modern influence of medieval manuscripts in the exhibition, and from the moment I contacted Philippa Broadhurst, who designed the prop, I have been overwhelmed by the interest and support we’ve received from The Jim Henson Company and Netflix in making this loan happen.

Date

February 3, 2020