Diversity in the Stacks: Afrofuturism

Today we launch a series of blog posts to celebrate the Penn Libraries’ Diversity in the Stacks initiative. Diversity in the Stacks aims to build library collections that represent and reflect the University’s diverse population. Our inaugural post highlights holdings related to Afrofuturism.

One of the most popular and actively researched sub-genres in academia today is Afrofuturism. The term was coined in 1993 to denote the movement of African, African-American, and other Black diasporic writers, artists, musicians, and theorists who address issues of blackness and race through speculative and science fiction. (If you’re interested in learning about Afrofuturism more broadly, check out this Oxford Bibliography Online.)

In 2018, Afrofuturism entered the pop-cultural lexicon because of major achievements in African-American filmmaking and literature. Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther enjoyed dramatic success at both the box office and awards ceremonies. Also, N. K. Jemisinbecame the first author to win the Hugo Award for Best Science Fiction or Fantasy Novel for three consecutive years, with each of the three installments of her Broken Earth Series garnering the award.

However, 2018 — and Jemisin’s achievement — was not wholly without precedent. There’s a long history of black writers working in the genre of science fiction. For example W.E.B. Du Bois’s short story The Comet imagines a post-apocalyptic world in which the sole survivors are a black man and a white woman. (For a cinematic version of a markedly similar story, see the 1959 film The World, The Flesh and the Devil, starring Civil Rights activist Harry Belafonte.)

More recently, Samuel Delany wrote a series of groundbreaking works in the 60s, and in 1972 the MacArthur ‘genius’ Fellow Ishmael Reed wrote the canonical Mumbo Jumbo. Beginning in the 1980s, a steady stream of popular and critically acclaimed works were published by authors such as Octavia Butler .

Musical pioneers of Afrofuturism, particularly Sun Ra and George Clinton, brought Afrofuturist lyrics and imagery to jazz and funk. More recently, Beyoncé’s landmark album Lemonade and the works of Outkast, Flying Lotus, Janelle Monáe, and Erykah Badu variously manifest Afrofuturist elements and sensibilities.

Afrofuturistic art is also represented in the collections of the Fisher Fine Arts Library. ArtStor contains images of work by artists such as Terry Adkins, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Wangechi Mutu, Angelbert Metoyer and others, and Fisher holds catalogs of exhibitions at which Afrofuturist work was shown.

Penn Libraries’ Franklin catalog is not readily searchable for fiction by theme, but some example of Afrofuturism are listed here. Scholars who are interested in exploring some of our more unusual holdings — including pulp fiction with original covers and rare comic books — may want to take a look at the Adams Science Fiction Collection and at the Comic Book Collection, both located in the Kislak Center for Special Collections.

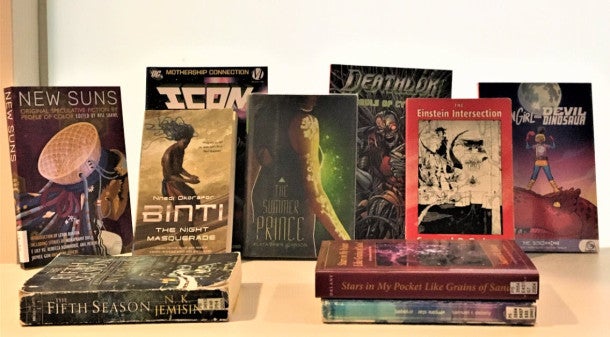

Below is a curated list of Penn Libraries’ holdings related to Afrofuturism:

- Blank Panther (comic book and graphic novel compilations)

- Kindred by Octavia Butler

- Stars in my Pocket Like Grains of Sand by Samuel Delany.

- Binti by Nnedi Okorafor

- The Fifth Season by N.K. Jemisin

- Brown Girl in the Ring by Nalo Hopkinson

- The Intuitionist by Colson Whitehead

- The Summer Prince by Alaya Dawn Johnson

- Cosmic Underground: A Grimoire of Black Speculative Discontent, catalog of the exhibit Unveiling Visions.

- Space is the Place, performed by the Sun Ra Arkestra

Date

September 24, 2019