Diversity in the Stacks: Indigenous Languages, Indigenous Voices

Diversity in the Stacks aims to build library collections that represent and reflect the University’s diverse population.

The United Nations declared 2019 to be an International Year of Indigenous Languages. At Penn, initiatives in support of the teaching and preservation of Indigenous Languages include teaching and conferences, and the EPIC project (Educational Partnerships with Indigenous Communities), whose partners include faculty in Arts & Sciences and staff at the Penn Museum. A number of Indigenous languages are taught at Penn through the Penn Language Center.

The UCLA Office of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion has provided some useful explanations of terminology, and they define the category “Indigenous” as follows: “Generally, Indigenous refers to those peoples with pre-existing sovereignty who were living together as a community prior to contact with settler populations, most often – though not exclusively – Europeans.” As UNESCO points out, “Indigenous peoples live in all regions of the world and own, occupy or use some 22% of global land area. Numbering at least 370-500 million, indigenous peoples represent the greater part of the world’s cultural diversity, and have created and speak the major share of the world’s almost 7000 languages.”

How many Indigenous languages might be represented in the holdings of Penn Libraries? Browsing the catalog reveals that over 500 languages are represented in the cataloged, printed holdings. Electronic resources provide access to many others. Specific collections have particular areas of concentration: for example, the collections of the Museum Library contain strong holdings in anthropology, including linguistic anthropology and materials on Indigenous languages from around the world.

But how do libraries categorize, inventory, or catalog such materials? One of the challenges faced by research libraries wishing to more fully represent the breadth of language holdings in their collections is that of description. Older catalog records tended to group Indigenous languages together under broad subject headings, rather than attempting to disaggregate and identify them. For instance, the subject heading “Indians of North America--languages” returns hundreds of results containing information about and often specimens of hundreds of Native languages of North America.

More recently, libraries have begun to undertake the work of identifying materials using terms that are developed through consultation with native speakers, rather than grouping materials according to more general linguistic headings and language families. In a recent post, Elliot Montpellier describes in detail the range of materials available in many Pakistani vernacular languages. The Center for Native American and Indigenous Research at the American Philosophical Society, which has extensive holdings of Native American language and cultural materials, is working with Native scholars and community leaders to reinterpret its holdings; it has published a collection guide that features a detailed language index. An open-source cataloging platform, Mukertu, developed at the Center for Digital Scholarship and Curation at Washington State University, has as one of its goals the inclusion of Indigenous categories and concepts in the descriptions of cultural heritage materials, “to empower communities to manage, share, narrate, and exchange their digital heritage in culturally relevant and ethically-minded ways.”

Challenges remain: for example, creating descriptions that include references to the presence of Indigenous languages within texts that are predominantly in European languages. Still more difficult to classify are works on pictorial-writing and sign systems, including, for example, pictographs, Incan khipus (also quipus), and Mayan pictographic writing.

As a contribution to this ongoing work, and as part of our Diversity in the Stacks initiative, I have highlighted a selection of materials in Indigenous languages from the Penn Libraries, produced from the seventeenth to the twenty-first centuries. In this cursory survey of a vast topic, I have selected fifteen collection items, many housed in the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts. Stretching across cultures and time periods, and produced in a variety of colonial and postcolonial contexts, these selections are meant to suggest the range of Indigenous language material available to researchers. Some materials have been digitized, and digital reprographic services are currently available to students and researchers.

Want to see more images of the books and manuscripts featured below? Check out our dedicated Facebook album.

Quechua

Juan Pérez Bocanegra, Ritual formulario, e institucion de curas . . .

Impresso en Lima: Por Geronymo de Contreras ... , año de 1631.

Rare Book Collection. BX2035.A5 S7 1631

The Quechua language is taught and studied at Penn. This is the oldest Quechua text at Penn: a collection of Catholic liturgical texts and sacraments printed in Spanish and Quechua, likely for the use of both missionaries and converts. It was assembled by Franciscan priest Juan Pérez Bocanegra, who, scholars have argued, had deep expertise in the Quechua language, particularly the form spoken in the region of Cuzco. The edition also includes a musical setting of a hymn to the Virgin Mary, Hanacpachap cussicuinin (modern orthography: Hanaq pachap kusikuynin). Penn has three copies of this edition.

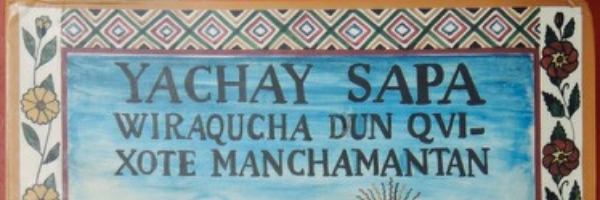

Miguel de Cervantes and DemetrioTúpac Yupanqui, Yachay sapa wiraqucha dun Qvixote Manchamantan [El Ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quijote de la Mancha]

Lima: El Comercio, 2005.

Rare Book Collection. Folio PQ6332.9 Q4 2005

This remarkable work is a translation of Don Quixote into Quechua by Demetrio Túpac Yupanqui, published in 2005. Quechua, as Américo Mendoza Mori, coordinator of the Quechua Program at Penn, has recently reminded us, is a living language, and Túpac Yupanqui’s project, according to commentator Lucas Iberico Lozada, was to “to create a standardized literary Quechua.” The book includes illustrations by artists in the Lima-based Asociación de Artistas Populares de Sarhua.

Kimbundu

Oraciones traducidas en la lengua del reyno de Angola . . .

En Lima: Por Geronymo de Contreras . . . , 1629.

Rare Book Collection. BX1965 J618 1629

Our third selection is also printed in Lima--but the Indigenous language printed here is not original to the Americas. It is Kimbundu, a Bantu language from the Angola region in Africa. This complex hybrid text is a Spanish-Kimbundu translation of a catechism originally written in Portuguese by Marcos Jorge. It was prepared to assist in the Christianization of enslaved Africans in Spanish colonial Peru. This very rare copy testifies to the complex paths Indigenous peoples took under forced migration, carrying their languages with them.

Berber

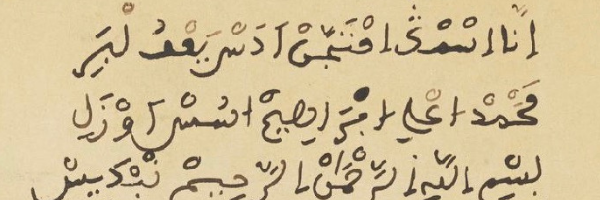

Muḥammad ibn ʻAlī Hawzālī, al-Ḥawḍ. Baḥr al-dumūʻ. = الحوض. بحر الدموع.

Manuscript, [Morocco], [between 1750 and 1850?].

Ms. Codex 1911

This manuscript from North Africa contains two works, both commentaries on Islamic theology and ritual practice by one of the most well known of the Berber writers, Muhammad Awzal (d. 1748 or 49). The works are in Shilha, also called Tachelhit, one of the more widely used Tamazight or Berber languages in Morocco and parts of Algeria. The alphabet used in the manuscript is Arabic and the script is Maghribī. This manuscript has recently been catalogued by Kelly Tuttle and digitized as part of the grant-funded Manuscripts of the Muslim World project.

Maninka

Nko : kodo-yidalan wala fasarilan haman kodofolan / Kante Sulemaana.

[Conakry: Librarie N'ko] or [Tokyo?: Kurukan Fuwa Gbara], [1992?]

This book is Maninka (also known as Manding and Mandingo) written in N'ko script, which was developed by the Guinean scholar Souleymane Kante (1922-1987). The Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics categorizes Maninka as one of “the Mande (or Mandé in French) language group” which “consists of some 30 languages spoken in West Africa from Nigeria to Senegal by an estimated 10 million speakers.” The Oxford Research Encyclopedia on Linguistics defines this community of speakers more broadly: “60 to 75 languages spoken by 30 to 40 million people” and notes that use of the N’ko script continues to increase. This book may have been printed in Tokyo rather than Conakry.

Nahuatl

La passión de n[uest]ro Señor Jesuchristo

Manuscript, [Mexico?, 18--?]

Berendt-Brinton Linguistic Collection. Ms. Coll. 700, Item 200

This manuscript is a Passion play, probably written and performed by Native converts in colonial México. These plays, performed during Holy Week, are hybrid texts. Professor Louise Burkhart (SUNY-Albany) has written that in performance they “exhibited compliance with colonial Christianization, but also presented a powerful appropriation of Christianity into Indigenous hands and Indigenous forms of religiosity.” Professor Burkhart has been investigating this play as part of a larger project on indigenous dramatic performance. Her analysis is available on her website, Passion Plays of Eighteenth-Century Mexico. This item and the next are part of the Berendt-Brinton Linguistic Collection.

Cakchikel

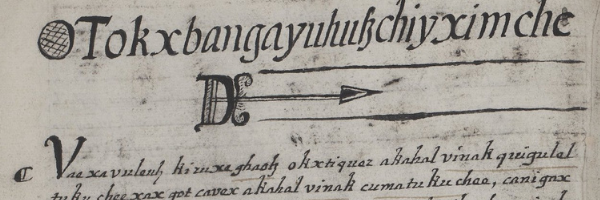

Manuscrito cakchiquel ó sea memorial de Tecpan-Atitlan (Solola) [Annals of the Cakchiquels]

Manuscript, [Sololá, Guatemala? between 1619 and 1650?]

Berendt-Brinton Linguistic Collection. Ms. Coll. 700, item 221

This manuscript documents the language and history of the Cakchikel-speaking people of Guatemala. Written in the early seventeenth-century in the Cakchikel language as transcribed in the Latin alphabet, the manuscript chronicles the Cakchikels’ history from their beginnings at Tulan until the early 17th century. It contains village and family histories and details pre-colonial rivalries as well as the Spanish conquest. Prepared in the context of Spanish colonization and missionization, the manuscript testifies to the power of community and of collective memory despite violence and cultural disruption. Acquired by the abbé Brasseur de Bourbourg in the nineteenth century, it was then acquired by Daniel Garrison Brinton. In 2017, officials from Sololá, Guatemala visited the library to view this manuscript.

Brinton’s library, more generally, includes materials in many Indigenous languages from across the Americas. Browse the holdings of the Brinton Library, part of the Museum Library’s collection.

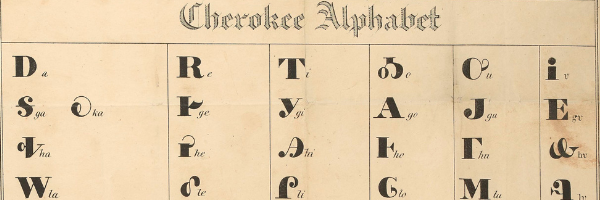

Cherokee

Cherokee alphabet [graphic] / Pendleton's Lithography, Boston.

[Boston: s.n., between 1826 and 1835]

Invented by Sequoyah around 1820, the famous “Cherokee syllabary” is a graphic representation of distinct syllables in the Cherokee language that was quickly adopted by Cherokees for writing and in print. This artifact, printed using a lithographic reproduction process in Boston, shows the syllabary’s rapid diffusion in North America. The date of printing is uncertain but is sometime between 1826 and 1835. Pendleton’s Lithography published popular prints and sheet music, but little is known about the circumstances surrounding their publication of this version of the syllabary. This document was acquired as part of the Peter M. McGowan Papers: McGowan, a Methodist missionary, worked with the Creek and Cherokee Nations in Arkansas.

The Robert Dechert Collection also includes a Cherokee printing of the Cherokee Nation Constitution and laws from 1893.

Mohawk

The Book of Common Prayer, according to the use of the Church of England / Ne kaghyadouhsera ne yoedereanayeadagwha : tsiniyouht ne yontstha ne Skanyadaratiha Onouhsadokeaghty, tekaweanatenyouh kanyeakehaka kaweanoetaghkouh.

[Hamilton? Ont.: New England Co.], 1842 (Hamilton: Printed at Ruthven's Book and Job Office)

Dechert Collection. PM1884 .C6 1842

Bible translations in Iroquoian languages are part of the long encounter between Haudenosaunee peoples (the Iroquois Confederacy) and Christianity, dating to the seventeenth century. This 1842 Book of Common Prayer in Mohawk, produced in Hamilton, Ontario, was the fifth edition to be printed. This copy, recently acquired by the Kislak Center for the Dechert Collection, appears to have been owned by a prominent Mohawk leader. It contains this inscription: “PRESENTED TO JOHN S. MARTIN BY THARACKATHA CHIEF OF THE MOHAWK INDIANS IN CAMP NEAR TYENDINAGA CANADA WEST JULY 4.TH. 1857”.

Penn’s extensive Bible collections include numerous Indigenous language translations. In particular, the Evans Bible Collection, approximately 400 publications, includes missionary translations of Christian texts in over 125 languages, with several dozen Indigenous languages from around the globe represented.

Kiribati (Gilbertese)

Te boki n anene ma b'ana : ae aia boki Kristian ni karaoiroa te Atua / e katauraoaki irouni Beiñam.

New York: E kaotaki iroun te Baba Hawaii : e boretiaki iroun te Biglow & Main Co., 1900.

Rare Book Collection BV510.G5 B56 1900

This book of hymns in the indigenous language spoken in the group of island atolls in the republic of Kiribati in Micronesia suggests the reach of Christian missionaries, many from the United States, during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This book was printed in New York for distribution by Hawaiian-based missionaries. The Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics describes Kiribati as follows: “The Kiribati language, also known as Gilbertese, is a Nuclear Micronesian language within the Oceanic branch of Austronesian. It is closely related to Ponapean, Kosraean, and Marshallese.” The hymns include transcribed Kiribati words.

Maori

Erima Maewa Kaihau, E moe te ra: waiata [Shadows of Evening]: song

Auckland, N.Z.: A. Eady, 1918.

Erima Maewa Kaihau, May I Not Love: song.

Auckland [N.Z.]: A. Eady & Co., 1918.

Marian Anderson Collection of Printed Music. M1495 .A64 Box 100A, Folder 15.

These two songs, with texts in English and in Maori, were sent by their composer, Erima Maewa Kaihau, to the singer Marian Anderson and are part of the Marian Anderson Collection. Maori is part of the Malayo-Polynesian language family and is the language of the Maori people of New Zealand. Erima Maewa Kaihau (1879-1941?) was a New Zealand songwriter who set Maori texts to music. Perhaps most famous for a song entitled Haere ra (Now is the hour), her songs have been characterized by New Zealand musicologists as a kind of “cultural blend” between traditional Maori music and European influences.

Sanskrit, Gujarati, Marwari

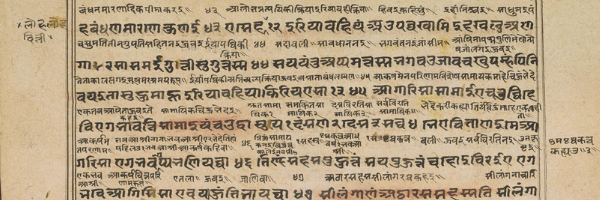

Pravacanasāroddhārasūtra, 1652. = प्रवचनसारोद्धारसूत्र, १६५२.

Ms. Indic 26

Penn’s South Asia Manuscript Collection includes a wide range of Indigenous languages, including some, like this, that include multiple languages. A work on Jaina doctrine (including cosmology, tīrthaṅkaras, siddhis, and asceticism), the manuscript includes a line by line commentary in Gujarati between the lines of Sanskrit text, accompanied by tables and paintings on Jain subjects. In his description of this illustrated manuscript for the 2017 exhibition Intertwined Worlds, Benjamin Fleming writes of this manuscript’s multlingual and multicultural significance: “A Jain work in Prakrit and Marwari languages from Rajasthan . . . The imagery evokes regional styles of Rajasthan, not particular to any one religious tradition, and here alluding to the Rajasthani love of horses.”

Kurdish

Kurdish primary school textbooks.

Beẍda: Wezaretî Meʻarîfî ʻÎrāq, 1955-1959.

Rare Book Collection. LB1556.7.I73 K8 1955

Rather than a single language, Kurdish is sometimes described as a group of related dialects spoken by the ethnic Kurds. A collection of Kurdish-language textbooks on a variety of subject and grades printed by the Iraqi Ministry of Education in the 1950s for use in Kurdish schools. Kurdish has been written using Arabic script but also using the Latin alphabet. Shown here: images from a geography textbook.

Irish

Songs and poems of the Gaelic League.

[Baile Átha Cliath: Chonnradh na gaedhilge, 1902-1928].

Rare Book Collection. Folio M1745 .G32

Irish may be considered an indigenous language of Europe: it: one of the surviving Celtic languages (along with Breton, Welsh, and Scots Gaelic). Founded in 1893, The Gaelic League (Conradh na Gaeilge) sought to encourage use of Irish (Irish Gaelic) as part of a program of literary and cultural nationalism. It encouraged the production of numerous publications.

Tlingit

Marie Olson, A Tlingit Coloring Book.

Auke Bay, Alaska: Heritage Research, [199-?]

Schimmel Collection. Schimmel Fiction 3558

Marie Olson, an Áakʼw Kwáan Tlingit of the Wooshkeetaan clan, has worked throughout her career to ensure the survival, revival, and persistence of Tlingit, an Indigenous language of Alaska. In 2019, she was recognized with a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska. Her bilingual coloring book is part of the Caroline F. Schimmel Fiction Collection of Women in the American Wilderness.

Learn more about the Tlingit people, their culture and language, in the Louis Shotridge Digital Archive at the Penn Museum.

Further Resources

The Linguistics-Research Guide lists databases, e-journals, reference works, and resources for specific languages. See also: Linguistics Collection (overview).

The Penn Museum Library’s collections focus on anthropology and world cultures, including language studies.

Date

December 8, 2020