Reflections on South Asia Studies Digital Humanities Workshop

On October 10–11, 2024, the South Asia Studies Digital Humanities Workshop (SASDHW) convened scholars, librarians, and technologists for two days of collaborative learning on multilingual and computational text analysis of South Asian sources. Participants explored the possibilities and limitations of cutting-edge Machine Learning (ML) applications with Optical Character Recognition (OCR) and Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR) tools for languages ranging from Sanskrit and Urdu to Tamil and Persian. Through a unique combination of traditional manuscript showcase, hands-on technical training, and transdisciplinary discussions, the workshop built a community of practice in which attendees gained new digital skills, brainstormed future projects, and critically reflected on how Artificial intelligence (AI) and Digital Humanities (DH) methods can aid in South Asian studies. Key outcomes included successful OCR of archival texts using Python, BBEdit, and Google Cloud Vision, cross-language transliteration with Sanscript, text analysis with tools like Google Pinpoint & Voyant Tools, and a shared commitment to preserving and promoting multilingual cultural heritage data. The following blog post reflects on the workshop’s activities and insights.

Origins & Motivation

In graduate school, I had worked on an exploratory data analysis of the Ancient Mycenean language, Linear A with Dr Anamaria Berea and Dr. Amira Al-Khulaidy Stine as a project for my “Principles of Knowledge Mining” & “Natural Language Processing” (NLP) class. In Summer of 2021, I started working on a Halegannada model based on the data from Epigraphia Carnatica Digitization Project with the Princeton Center for Digital Humanities, DARIAH-EU, and NEH-funded New Languages for NLP initiative. Alas yet hurrah, here I was to encounter the bane of South Asian Digital Scholarship writ large - OCR Accuracy. Ah, machine readability of non-Roman scripts! One of my many #DHFailures (Dombrowski, 2019) includes not producing a usable and annotated model of Ancient Kannada scripts with Named Entity Recognition (NER) as a definitive outcome for this workshop series. The purported use case was to extract the trade routes in Hoysala kingdom’s King Ballala era in the Deccan Karnataka plateau. Apart from not having the context for humanistic inquiries and research questions, I could not even get to the stage of having an annotated dataset, without accessible machine-readable text. However, I did learn a lot about the process, and most importantly, found an incredible community of like-minded researchers.

Another profound takeaway for me was the run-of-show—the thoughtful structuring of a workshop designed specifically to address the unique challenges of digitally disadvantaged languages. The format, the pacing, and the pedagogical care woven into each session offered a template I continue to learn from. I remain deeply inspired by the work of Andy Janco, Natalia Ermolaev, Quinn Dombrowski, Toma Tasovac, Nick Budak, David Lassner, and so many others whose contributions shaped not only this event, but the broader landscape of technical Digital Humanities workshops. Their dedication and vision continue to guide my thinking and practice to this day—and, I imagine, will do so for a long time to come. This is the kind of work I have long yearned to replicate for other South and Southeast Asian scripts, and this experience reaffirmed just how urgent and possible that vision can be.

First, I needed to understand and be able to communicate with humanities researchers. Speaking the language of Humanities, would help me become a better scholar of DH. It would also enable me to showcase the value of DH to South Asian studies researchers better, for this work simply could not be done alone; it had to be done collaboratively. So I started by taking Dr. Daud Ali’s “Making of Medieval India”, Dr. Sonal Khullar’s “Indian Paintings”, Philadelphia Museum of Art Paper Conservation Lab’s “Methods of Object-Study: Understanding Works of Art on Paper,” making use of the tuition benefits afforded a full-time staff member.

At the 50th Annual Conference on South Asia 2022, I attended a talk by Dr. Andrew Ollett, who had been working on extracting text from historical Kannada and Sanskrit plays for his philological research. Meanwhile, I reached out to faculty and staff at Penn’s South Asia Studies department.

Back at Penn, I became involved with the Schoenberg Institute of Manuscript Studies to consider the workflow pathways for enabling the use of manuscript collections as data for further research. Having noted that the Kislak Center for Special Collections and Rare Book Manuscripts hosted around 3000+ Sanskrit manuscripts and a significant amount of South Asian manuscripts in general (many acquired by Dr. Norman Brown), I began experimenting with OCR/HTR tools and technologies with some of these manuscripts.

Lo and behold, Dr. Kashi Gomez, a Sanskrit lecturer in the department, and I started discussing different Digital Humanities methods and techniques relevant to the field. In September 2023, I helped troubleshoot Python code for an intriguing OCR workshop she had attended, by Professor Andrew Ollett.

As Gomez and I celebrated successfully extracting Harṣacarita texts in near perfect Devanagiri scripts, the idea to collaborate on a one-of-a-kind multi-department DH workshop started brewing.

A Different Kind of DH Workshop

Digital Humanities approaches have enormous potential for South Asian studies, yet opportunities to learn the requisite tools in a domain-specific context remain rare. The SASDHW was conceived to fill this gap by offering a hands-on, critically-informed training ground tailored to the needs of South Asian textual scholars. Unlike typical workshops that might focus only on showcasing DH projects or remain discipline-specific, this event blended material exploration (through a manuscript showcase), hands-on live coding, and transdisciplinary pedagogy (bringing together area specialists, librarians, and tech experts as equal partners). We emphasized from the get-go that the workshop would be inclusive of all experience levels – answering questions like “Who is this workshop for?” and “Do I need tech expertise to be here?” – and grounded in values of openness and collaboration. In her welcome remarks, Gomez contextualized the need for Digital Humanities in South Asia Studies and highlighted the collaborative efforts that made the event possible.

Crucially, SASDHW was structured as a hybrid event: morning sessions were open to the public (with a live stream and recording), while afternoon sessions were closed to a cohort of about 20 selected hands-on participants who committed to both days. This design allowed broad knowledge-sharing while also providing an intensive learning experience for the core group. The workshop was sponsored by six University of Pennsylvania entities – the Department of South Asia Studies, the Penn South Asia Center, the Penn Libraries Research Data and Digital Scholarship (RDDS) unit’s AI Literacy Interest Group, the Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies (SIMS), the Price Lab for Digital Humanities, and the Wolf Humanities Center – reflecting a strong institutional commitment to building DH capacity in South Asian studies. An audience of roughly 70 people (about 50 in person and 20 online) attended various portions of the event, including faculty, graduate students, and independent researchers from Penn and beyond (with participants joining us from other U.S. universities, Canada, and India). Of these, 20 were full-time workshop participants who engaged in hands-on coding and project development. The workshop aimed to introduce these scholars to OCR/HTR techniques for turning archival sources into searchable texts and to foster an interdisciplinary dialogue on multilingual “collections as data” (Padilla et al. 2018) in the South Asian context.

Why was such a workshop needed?

South Asian textual materials pose unique challenges for textual extraction: they span dozens of languages and scripts (often under-resourced in OCR training data), include centuries of handwritten manuscripts and lithographs, and embody rich cultural contexts that pure technical solutions alone cannot fully address. Prior DH initiatives in South Asian studies have often been high-level conferences or digital library projects; by contrast, SASDHW offered a hands-on, intensive training where scholars could actually learn and apply tools to their own research materials. This focus on experiential learning “learning by doing” – with technical experts on standby to assist – set the event apart. Moreover, the inclusion of a physical manuscripts viewing session signaled a commitment to humanities-forward approach: before diving into code, participants were prompted to examine the tangible sources of our data and consider how knowledge is transformed when a manuscript becomes a machine-readable text.

Participant Motivations

The cohort of hands-on participants in SASDHW reflected the workshop’s goal of fostering an inclusive, multilingual, and multidisciplinary space. Attendees included graduate students, faculty, postdoctoral researchers, and librarians from across the U.S., Canada, and India. Many were affiliated with South Asia Studies, Comparative Literature, Religious Studies, and Early Modern Studies programs. Several had no prior coding experience, while others brought background in engineering, or manuscript research.

Their reasons for attending were diverse but deeply thoughtful. One participant noted they joined to “learn skills that I can apply to my work in the future and help with digitization efforts in Mauritius,” where colonial multilingual archives remain under-digitized. Another said simply: “No experience but want to learn.” Others were drawn by research needs: a Hindi-Urdu scholar aiming to “OCR my personal collection of rare PDFs,” or a linguist working on dialectology in the Hindi belt seeking tools to analyze regional script variation. A recurring theme in their responses was the desire to bridge traditional text-based scholarship with digital tools – not to abandon close reading, but to expand its scope through scale and searchability.

Participants were interested in working on or researching at least 17 South Asian languages including Sanskrit, Urdu, Prakrit, Tamil, Gujarati, Malayalam, Awadhi, Apabhramsha, and Persian. Some were interested in creating OCR-ed corpora for Sanskrit commentaries; others wanted to map language change across decades in Devanagiri manuscripts. One participant wrote: “My work includes studying Urdu poetry texts by South Asian women poets. OCR would make it easier to work with archives scattered across collections.” This multilingual, motivated group ensured that the workshop was always rooted in real scholarly inquiry – not demos for their own sake.

In summary, SASDHW cultivated a learning community across varying expertise levels, demystifying technology for humanities specialists (some of whom had “no experience but eager to learn” as one registrant put and simultaneously encouraging tech-savvy participants to grapple with the interpretive and ethical dimensions of their tools. The remainder of this post provides a chronological walkthrough of the two-day workshop, followed by reflections on its outcomes and future directions. Additional workshop materials, including Code Notebook, Handout, and images available in Box Folder.

Day 1 (October 10, 2024) – From Manuscripts to OCR

Video Time stamps

0:00-9:52 Welcome by Kashi Gomez

18:05 Introduction to Manuscripts by Dot Porter

10:00 South Asian Manuscripts Showcase

24:35 Manuscript Collections Materials Showcase

1:09:14 Text as Data Keynote by Andrew Ollett

2:05:01 Hands-on Workshop Software & Installation Check

2:26:22 Google Cloud Vision API

2:43:24 BRISS

2:50:52 OCR

9:15–9:30 am – Welcome & Acknowledgements: The workshop opened in the Class of 1978 Orrery Pavilion with coffee and a sense of excitement. Kashi Gomez delivered a warm welcome for all including the special guest of honor Dr. Andrew Ollett, introducing the goals of the workshop and thanking the sponsors and support teams that brought it to fruition. In framing the event, Gomez stressed an ethos of inclusive experimentation: this was a space where South Asianists with minimal tech background could feel comfortable, and where computational experts could learn about the cultural specificities of South Asian materials. She posed guiding questions (e.g., What values does this workshop honor?) and reassured attendees that no advanced technical expertise was required to participate. She shared how she relies on OCR in her own work, as a demonstration of the impact of technical HTR knowledge in her research. Jaj Karajgikar joined in highlighting the transdisciplinary nature of the endeavor – a product of collaboration between academic departments, libraries, and digital scholarship units. The organizing team introduced at this stage included not only Gomez and Karajgikar as co-organizers, but also a cadre of facilitators from Penn Libraries: Eug Xu (Data Science & Society Research Assistant), Dot Porter (Curator of Digital Humanities, SIMS), Andy Janco (former Research Software Engineer, RDDS), Doug Emery (Digital Content Programmer, Cultural Heritage Computing or CHC), and Jessie Dummer (Digitization Coordinator, CHC). Their presence underscored that participants would have guidance in both content and technical domains throughout the workshop.

10:00 am – South Asian Manuscripts Showcase: The first substantive session exemplified the workshop’s blending of traditional and digital perspectives. Dot Porter, along with Jaj Karajgikar and Eug Xu, led a showcase of curated South Asian manuscripts from Penn’s Kislak Special Collections (Manuscripts of the Muslim World and Collection of Indic Manuscripts, etc.) as well as maps from the Zilberman Family Center for Global Collections. Along with Michael Carroll, the Assistant Director of the Fisher Fine Arts Library, we curated a showcase of traditional writing implements and textiles from the Materials Library.

Several rare manuscripts and fragile texts spanning multiple languages and scripts were displayed on tables for participants to examine up-close. These included, for example, a 17th-century Persian astrological compilation and Sanskrit literary works on palm-leaf and paper. As attendees circulated around the exhibits, the facilitators prompted discussion on key questions:

What is the connection between material objects and computation?

Why would a particular text be challenging to OCR?

How do analog objects provide training data for LLM?

What challenges in the OCR/HTR process would you foresee?

How does material medium affect OCR/HTR?

How would you map these texts?

What connections would you want to make in the content of the text?

Participants and facilitators examine South Asian manuscripts laid out for the showcase in Penn Libraries DH+Texts room.

The room came alive with conversation as South Asianist scholars pointed out challenging features – antiquated scripts, worm-eaten pages, complex layouts, marginalia – that might confound OCR algorithms. Porter illustrated how certain Bengali and Oriya script manuscripts have ornate ligatures that are especially hard for machines to parse without extensive training data. I noted that the very presence of these digitized collections in libraries (through efforts like Penn’s Colenda digital repository and OPenn) feeds into the datasets that AI models learn from; in other words, colonial-era texts and modern scans alike become the “ground truth” for OCR/HTR systems. By the end of this showcase, participants gained a visceral appreciation for the materiality behind digital text corpora. As one attendee put it later, the exercise seemed to lower the barrier of entry and gave insights into the challenges of OCR and the importance of training data for AI models.

Notably, this manuscript showcase session was conducted in a hybrid format: in-person participants could view the items directly, while virtual attendees were accommodated via a live video feed with commentary. This “hybrid manuscript viewing” inspired by Coffee with Codex and Manuscript Interest Group was an experiment in itself, bringing physical archives to digital audiences – a fitting metaphor for the workshop’s ethos. Penn Libraries itself has a long history with South Asian manuscript acquisitions, and attempting to provide public access to them, in various ways. The showcase underscored that any computational analysis of South Asian texts must reckon with the knowledge embedded in physical objects and human labor of digitization. It set an epistemological grounding for the technical sessions to follow, reminding everyone that behind every digital text file stands a chain of material and human processes.

11:00 am – Keynote: “Texts as Data – Tools and Perspectives for South Asianists”: With the context established, the workshop shifted to a keynote talk by Dr. Andrew Ollett (University of Chicago). Ollett’s presentation – delivered to a full room and Zoom audience – delved into how treating texts as data can open new research avenues for South Asian studies. Drawing on his experiences with Sanskrit and Prakrit literature, Ollett discussed the potential of OCR and HTR tools for dealing with the vast textual heritage in languages like Sanskrit, Tamil, Pali, Urdu, and more. Ollett opens by situating manuscripts not as static artifacts but as datasets ripe for computation. He argues that understanding the materiality of parchment, paper, and ink is essential to any OCR/HTR pipeline—image preprocessing choices (deskewing, contrast normalization) profoundly affect downstream accuracy, for South Asian scripts with dense ligatures, getting that first step right is non-negotiable. He showcased examples from his own projects where digital tools had facilitated philological research: for instance, using regex (regular expressions) to search for linguistic patterns across a large corpora of texts, or employing OCR on printed editions to rapidly extract and compare commentary variations. At the same time, Ollett did not shy away from the challenges. He emphasized that applying computational methods to multilingual texts is inherently difficult – scripts like Devanagari, Perso-Arabic, Kannada, and Tamil each present distinct OCR hurdles, and many South Asian languages lack the extensive OCR training sets available for European languages. Moreover, historical documents (handwritten or early prints) often yield error-ridden OCR output, requiring scholars to remain critical of the results. Dialectal variation (e.g., Maithili vs. Magahi scripts) demands multiple “dialect-specific” models rather than one monolithic system. Metadata normalization where the same place-name might appear in Prakrit, Persianate, and English colonial registers, complicating any attempt at large-scale “text as data” queries.

Here, Ollett advocates for a “data-aware philology” where OCR/HTR outputs feed directly into digital editions, corpus linguistics tools, and downstream NLP pipelines.

Ollett’s talk thus balanced optimism with caution: he portrayed digital tools as transformative for research – analysis of how verbs collocate with nouns across – yet he also advocated for deep area knowledge to interpret computational results correctly. The audience was engaged throughout, with questions ranging from technical (e.g., how to handle Sanskrit sandhi in text mining) to methodological (the role of DH in decolonizing South Asian archives). For many attendees, hearing a leading South Asian Studies Philologist speak passionately about Python scripts and OCR workflows was inspiring. As one faculty participant later reflected, the keynote helped in “getting over my anxieties about how DH is useful by concretely demonstrating use cases in our field.”

12:00 pm – Lunch Break (and Informal “Loom Weaving” Demo): Alongside, food from a local Tibetan Nepali restaurant (White Yak) catering to the group, the organizers had arranged a creative surprise – a loom weaving activity in RDDSX. A portable traditional rigid-heddle handloom was set up, and participants were invited to try weaving a few threads. This activity, led by a Eug Xu, was more than a meditative diversion; it served as a metaphor for the workshop’s themes. Weaving threads into a fabric echoed the way data strands (bits of OCR’ed text, transliteration schemes, metadata) are woven together to create a digital representation of cultural heritage. It also connected to South Asia’s rich textile traditions, subtly reminding participants that craftsmanship and technology have long histories (the Jacquard loom, after all, was an early inspiration for computing). The sight of scholars and coders taking turns at the loom underscored the workshop’s blending of analog and digital, past and future. Conversations about sentiments around AI & technology became apparent on the weaving as a data physicalization. This #DHMakes (Visconti, et al., 2024) Energized by food and this hands-on critical making exercise, the group reconvened for the afternoon’s intensive coding sessions.

1:00 pm – Software Installation Check: After lunch, the venue shifted fully to the hands-on workshop mode (as an in-person only closed session where participants pre-registered with more intensive project requirements and applications). Instructors Jajwalya Karajgikar and Kashi Gomez kicked off with a “software and installation check” – essentially ensuring every participant’s laptop was set up with the required tools. I showed the workshop participants a short demo of the Text Detection using Google Cloud Vision API (GCV API.) This demo works for 1 page scan and detection at a time, but for larger documents, we had to get into the code.

In the weeks prior, attendees attended a hybrid Python Installation Party (PIP, an insider coding joke) to install a suite of software:

- Python (with some libraries and scripts prepared)

- Text editor (e.g., BBEdit for Mac or Notepad++ for Windows)

- Sanscript transliteration Python package

- BRISS (an open-source PDF page cropping tool)

- Additionally, each participant had a Google Cloud account set up to use the Google Cloud Vision API for OCR.

Despite a preparatory installation session held earlier, inevitable tech hiccups remained: a few participants on Windows struggled with setting environment variables for Python, while others needed help updating pip packages. The facilitators moved around the room to troubleshoot. This segment also introduced basic command-line skills – for some humanities scholars, typing commands into Terminal or PowerShell was a completely new experience. The patience and encouragement in the room were palpable; more experienced participants and staff paired up to assist beginners, embodying the spirit of computational community building. By the end of this check, everyone could run a simple “Hello World” Python script and had the OCR utilities ready to go. In the process, as one participant noted, attendees gained “practical skills in setting up and using digital tools” through this exercise.

2:00 pm – Preparing Text for OCR/HTR: With systems ready, attention turned to preparing the archival documents themselves for optimal OCR/HTR processing. This session was led by Andrew Ollett (now rolling up his sleeves as an instructor) with support from Andy Janco, who specializes in multilingual text extraction, model development, and generation.

Participants had been asked to bring or identify sample pages from manuscripts of interest – many had images or PDFs from Penn’s collections (or personal archival research) in languages such as Hindi, Sanskrit, Urdu, Gujarati, and Malayalam. Gomez introduced the concept of segmentation: to achieve better OCR, one often needs to segment multi-column pages or isolate text from surrounding borders. Using BRISS, a tool for splitting and cropping PDF pages, everyone practiced cutting a PDF scan into individual text block images. For instance, a Sanskrit manuscript page with two columns and an ornate border was divided into two single-column images, and excess margins were removed, to reduce OCR confusion. The instructors also discussed image preprocessing tips – e.g., adjusting contrast, ensuring the image is correctly rotated – although for simplicity these were mostly demonstrated rather than done by each person. By preparing their input data in this way, participants learned a key maxim of data science: garbage in, garbage out. Careful curation of the input images would significantly improve the text output later. In parallel, the notion of transliteration standards was introduced. Since some OCR engines (like Google’s) might output Devanagari text or romanized text, and since scholars may wish to work in transliterated Latin script for analysis, the group discussed schemes like IAST and ISO 15919. The Sanscript Python library, which can convert text between scripts (e.g., Devanagari to Roman), was briefly shown as a solution we would use after OCR. This forward reference prepared everyone to understand the pipeline:

Scan image → OCR engine yields text → use Sanscript to transliterate if needed.

Participants were excited to see the pieces of the puzzle coming together.

3:00 pm – OCR/HTR with Google Cloud Vision and Python: The culmination of Day 1 was the hands-on OCR exercise using the GCV API with Python. Andrew Ollett took the lead, projecting his screen and walking through the process step by step. Here we were making use of Ollett’s documentation from the workshop Gomez had attended: http://prakrit.info/dh/ocr.html. Each participant had been provided with a Python notebook/script (adapted from documentation on Ollett’s website) that sends an image to GCV and returns detected text. Over the next hour, the room alternated between intense focus and eureka moments. First, attendees set up authentication to the Google Cloud service (copying API keys, a hurdle for some). Then, they ran the OCR on a test image – for example, a printed Hindi page – to familiarize themselves with the output format (JSON with text annotations). With that working, participants moved on to their own selected images from earlier. This was where the true test came: would the state-of-the-art OCR handle these diverse South Asian scripts? In many cases, yes – at least for printed texts. One participant fed in a scanned Urdu poem and was thrilled when the Urdu script came back correctly recognized in Nastaliq font. Another used a Sanskrit print in Bengali script (Bangla letters) and obtained highly accurate Unicode Bangla text, which they then transliterated to Devanagari using the Sanscript code snippet provided. However, not everyone had immediate success. A researcher trying a cursive Persian manuscript received mostly gibberish output, highlighting the still-unsolved challenge of HTR (handwritten text recognition) for such materials. The instructors encouraged them to try a different sample or adjust image quality, but also pointed out that current AI might simply not be trained on that handwriting style – underlining the need for more training data from Persian archives. Through trial and error, every attendee eventually managed to obtain at least one useful text extraction. In fact, by the day’s end everyone had successfully generated at least one OCR transcription from their chosen documents. The triumph was evident – one group’s feedback notes later gleefully read, “Got everything to work! Yay! … Feel like I can replicate my script, and be able to explain this process to others.” Ollett described the sense of awe and pride that accompanies receiving an output not just from printed material but also handwritten manuscripts. Another professor wondered if this could be extended to epigraphical records too. The sense of empowerment was palpable as people realized they now had the tools to turn images into searchable text. Participants noted key takeaways such as understanding why OCR might fail in certain cases and how transliteration can make texts comparable across scripts. They also appreciated the incidental learning of command-line and coding fundamentals that came with the exercise. As one candid bullet point in a group recap admitted, the instructions were clear, but “underlying principles [were] less clear” and “troubleshooting issues in terminal feels daunting” – a reminder that there was still a learning curve to conquer. Nonetheless, the overall mood was proud and optimistic: the day had demystified technologies that once seemed out of reach.

4:30 pm – Reception: Wrapping up Day 1, a casual reception was held, giving everyone a chance to unwind and network. Over hummus, and grilled delicacies, participants exchanged stories of their OCR wins and woes. This social time also nurtured the nascent community – a PhD student in Urdu literature found colleagues who were working with similar archives, a historian discussed with a data engineer how to perhaps train a better model for naastaliq script, and so on. The backdrop to the reception was again the clack of the handloom: the weaving project begun at lunch continued, with many taking another turn. By now the partially woven fabric had become a tangible symbol of the group’s collective effort – each adding a thread just as each had contributed a question or insight during the day. With smiles and renewed energy, participants left for the evening, eager to return for more in Day 2.

Day 2 (October 11, 2024) – Analysis, Reflection, and Future Plans

Time stamps

0:00 - 49:24 DH-ifying South Asia Studies by Jaj Karajgikar

49:25 - 1:25:59 OCR Workflow

1:26:00 Computational Text Analysis Tools for Multilingual Research

2:11:57 Brainstorming Data-Driven Multilingual / Non-English Research Questions and Projects

2:22:45 Workshop Outcomes Presentations

9:30 am – Coffee & Networking: The second day started with a relaxed coffee period. Some new faces from the public joined to hear the morning talks, while the core workshop group reconvened, many cheerfully comparing notes on how sore (or not) they were from coding the previous day. The multilingual nature of the cohort was again evident – one table chatted in Hindi about OCR issues, another discussed Urdu scripts in Telugu and Tamil. The organizers encouraged participants to share any overnight thoughts or questions on a communal whiteboard. A few had written comments like “How to handle mixed-language documents?” and “Curious about tools beyond OCR – topic modeling next?” These would feed into discussions later in the day.

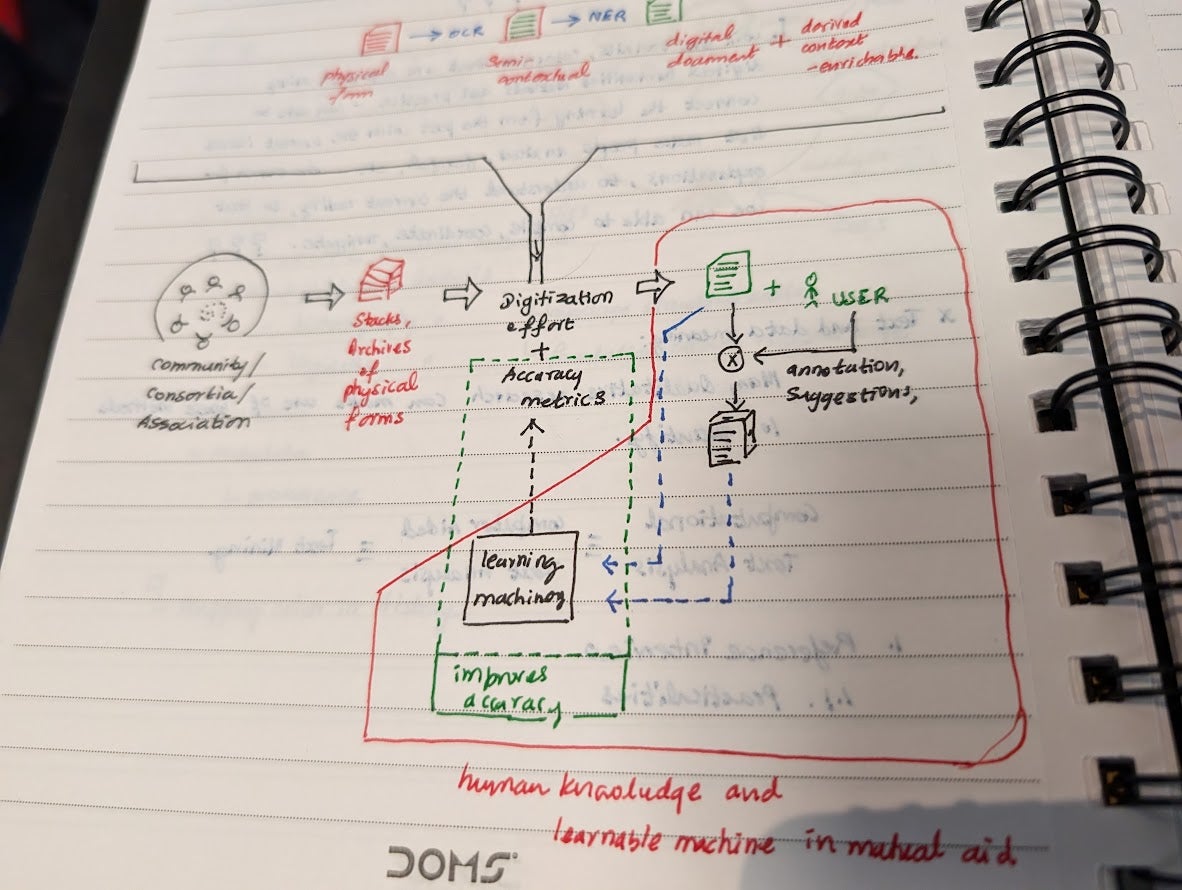

10:00 am – Talk: “My Case for DH-ifying South Asia Studies”: The Day 2 public session opened with a talk by Jaj Karajgikar, effectively flipping the script by offering a librarian’s perspective to a room of subject matter experts. In the talk, Karajgikar presented an autoethnographic account of coming to the humanities from a computational background. She recounted her experiences working as an applied data science librarian supporting researchers across disciplines, and how that revealed both the benefits and blind spots of applying AI/ML techniques to humanistic inquiry. For South Asian studies in particular, she argued, there is immense untapped potential in harnessing digital methods – from mining colonial-era administrative records for hidden narratives, to using named-entity recognition on literary texts to map geographies of trade routes. But she also cautioned that without domain knowledge, digital analyses could easily misinterpret non-Western contexts. Karajgikar’s talk was a call to action for building bridges: between library science and area studies, between technical experts and linguistic/cultural experts. She shared a slide of her early attempt to OCR a Halegannada document that ended in a garble, illustrating how she had to learn about scripts and transliteration to make sense of it. Her journey “from the other side” resonated with attendees who likewise were journeying into DH from the humanities side. The audience engaged with questions about institutional support and how to sustain this emerging community. One question – “How do we keep momentum after the workshop?” – led to a fruitful group discussion about forming a reading group or working group for South Asia DH, which organizers took note of as a next step to facilitate.

11:00 am – OCR Workflow Recap

12:00 pm – Lunch & Feedback: Lunch on Day 2 (courtesy of a local Indian eatery, Masala Kitchen) was both a meal and a reflection period. Over delicious kathi rolls, participants were encouraged to discuss in small groups two questions: “What was your biggest takeaway from the workshop so far?” and “What’s one idea for a project or research question you’re inspired to pursue now?” The room buzzed with conversation. Many expressed excitement about concrete skills – “It was a cool skill I learned, which will be handy when transcribing manuscripts and my own notes,” said one student about the OCR workflow. Others spoke about a shift in perspective – one faculty member shared that being able to search across digitized texts gave them new ideas for organizing their personal archives, planning “to use this to produce [a] public database” of sources. A librarian participant noted the importance of community, saying their takeaway was that increasing critical, fearless, compassionate dialogue between disciplines is possible when working on hands-on projects. The informal loom weaving station was active again, now more vibrant as a multicolored textile; a literal tapestry of SAS DH community. As lunch wrapped up, we asked everyone to jot down any “one thing you’d do differently or suggest for next time.” Some responses were technical (e.g., “More proactive support for the Windows folks”, acknowledging the extra challenges some had with setup), while others requested advanced topics for future workshops, such as demonstrations of specific applications like Dharmamitra (a Vedic text analysis tool) and workshops on geospatial mapping or more Python troubleshooting practice. It was clear that the workshop had whetted appetites for further training.

1:00 pm – Multilingual Computational Text Analysis Tools: The final instructional session, led by Jaj Karajgikar, shifted focus from data capture (OCR/HTR) to data analysis. Titled “Computational Text Analysis Tools for Multilingual Data,” it introduced participants to techniques for examining and querying the texts they had now digitized. I demonstrated a three-part toolkit to work with the freshly generated texts:

(1) employing Google Pinpoint (a Google tool for searching across a corpus of documents with regex and filtering capabilities) for more powerful query and entity extraction, and

(2) visualizing word frequencies and patterns with Voyant Tools (a popular web-based text analysis platform).

Importantly, these tools were shown handling non-English scripts and transliterations. In Pinpoint, I uploaded a set of OCRed texts (some in Urdu, some in Hindi) and demonstrated how one could quickly find all occurrences of a name or date across the collection – a technique invaluable for historians dealing with large archives. I demonstrated this with the semantic search of all instances of the entity “Buddha” occurring across the sample texts, in all variations of his name; Gautama, Siddhartha, Laughing Buddha, etc.

The Voyant demo drew audible “wows” as I fed in a Hindi corpus and produced a cirrus word cloud and trend line diagram. Seeing terms appear in Nagari script in the word cloud underscored the progress: just a day ago some participants didn’t know how to get machine-readable Hindi at all, and now they had the means to envision analytical outputs. A participant commented in chat that “tools like Voyant can help synthesize hundreds of readings and notes into a heatmap of major concerns… helping form coherent threads”, showing that attendees were already imagining how to apply these techniques to their own literature reviews and research notes.

At the same time, I cautioned the group that interpretation is key – a word cloud might show frequency, but the researcher must supply the context to understand why those words matter. The session overall expanded everyone’s view from digitizing to analyzing texts, emphasizing that OCR is just the first step toward digital scholarship. It answered the recurring question of “Now that I have the text, what next?” with accessible, free tools that participants could continue to explore after the workshop.

2:00 pm: Brainstorming Data-Driven Multilingual / Non-English Research Questions and Projects: The rest of the afternoon was devoted to collaborative ideation. Participants were divided into small breakout groups, roughly by shared language or interest (hence the language table placards like those pictured earlier). Eug gave a short presentation of in the provided template for the workshop reflections:

OCR/HTR Successes and Struggles

What kinds of research can you imagine posing with access to a large archive of searchable texts?

Imagine and describe future digital humanities project(s) for your field of study

Assess the challenges of your imagined projects

3:00 pm – South Asian Collections as Data Research Group Presentations & Discussion: Each group was tasked with imagining a future research project (or set of research questions) that could be pursued using the digital scholarship methods learned, and to consider the practical challenges in doing so. Flip charts and markers were provided, and groups had about an hour to discuss and compile their ideas. One group containing several Sanskritists and a linguist envisioned creating a database of early 20th-century Hindi literary texts to track how key literary terms (like kavita vs. kavya for “poetry”) evolved over time. They even hypothesized checking verbs used with “poetry” across dialects – e.g., “kavitā karnā” vs “kavitā likhnā” – to see shifts in conceptualization of authorship. Another group, which included an Urdu literature student and a researcher from India, proposed building a searchable archive of South Asian feminist journals, combining OCR with metadata tagging to enable cross-language search (Urdu, Hindi, English) for feminist discourse in the 1950s. A third group with interest in Sanskrit manuscripts brainstormed a project to OCR and transliterate śāstra texts (like a set of philosophy treatises), then use text mining to find intertextual references across them – effectively mapping a network of quotations and commentary. They noted the limitation that many śāstra manuscripts are handwritten, so a prerequisite would be training a custom HTR model or crowdsourcing transcriptions. Across groups, common “imagined projects” included ideas like digitizing entire archives to enable keyword search (one participant wrote about “doing OCR searches on my massive collection of PDFs in Indian scripts” as a near-term goal) and cross-lingual analysis (e.g. comparing how a concept appears in Sanskrit vs. vernacular texts).

Each group also enumerated challenges: unsurprisingly, issues like handwritten material, OCR error rates, alignment of text and images, and need for domain-specific training data came up repeatedly. Groups were forthright about obstacles – one list mentioned the “political economy of present academia, where time is money” and questioned if DH efforts would be valued in one’s career – but they also brainstormed solutions, such as seeking institutional support or forming collaborative teams to divide labor. This exercise not only sparked concrete research ideas but also served as a reality check: participants confronted what it would take to move from a workshop proof-of-concept to a full-fledged project. In doing so, they reinforced a core theme: community and collaboration are key to sustaining digital scholarship in South Asian studies. To all of our great amusement, one group demonstrated how Google Pinpoint OCR-d the title śrī as SRK, thus categorizing the Bollywood actor, Shah Rukh Khan as an entity in 17th century texts.

Throughout these presentations, participants cited not just what they did, but how it changed their mindset. For instance, one group’s slide listed as a “Day 1 success”: “Reviewed useful command line skills… feel like I can replicate my script”, but under struggles: “If I had to teach someone else, I can’t as of now… underlying principles less clear” – an honest self-assessment that drew supportive nods. Another group said their big win was simply overcoming fear: “It surpassed my expectations. Thank you!” was written on their sheet, capturing a sentiment many echoed. Indeed, as groups shared final thoughts, multiple attendees mentioned a boost in confidence. What two days ago seemed intimidating – e.g., using a terminal, handling data files – was now demystified. The session closed with a round of thanks and a few final questions from public attendees who had come for the presentations. One question from a South Asian studies librarian in the audience was, “How do we continue this momentum?”

Participant's notes from the Workshop sessions

I had to acknowledge all my inspirations, support systems, and workshop facilitators once more – from library IT staff who ensured the hybrid infrastructure worked, to the Special Collections staff who hosted us and the manuscripts showcase, and administrative staff like Courtney Brennan who coordinated logistics. The room gave a round of applause to the often-unsung helpers (Eug, Andy, Doug, Jessie, Aleta Arthurs, Aurora Reardanz, among others) and to the sponsors that enabled this event. In closing, Gomez invited everyone to stay in touch and to consider writing short pieces about their experiences for the department newsletter or the library blog, to further disseminate what was learned.

Conclusions and Next Steps

As the workshop officially concluded, there was a palpable excitement about possibilities ahead. Participants lingered to exchange contact information and even to add final weaves to the now-completed loom textile. In a sense, the workshop had woven together a new interdisciplinary network. The impact of the two days was evident in both tangible outcomes and intangible shifts: tangible in the form of OCRed text files, code snippets, and project plans that people were taking with them; intangible in the form of greater confidence, new friendships, and a shared vision that computational methods can enrich the study of South Asia’s past and present. Participants left with concrete learning outcomes – they could prepare images for OCR, run an OCR script, transliterate outputs, and perform basic text analysis – and many voiced ideas for future research that they were now equipped to pursue, from building digital text corpora to mining government records. Feedback collected in an exit survey was overwhelmingly positive: attendees described the workshop as “transformative,” praised the “enthusiasm and approachability” of instructors, and appreciated how it “surpassed my expectations”. Some constructive suggestions included extending the workshop duration in future and offering breakout sessions by skill level. A recurring theme in feedback was the value of the community formed – participants felt less alone in their interest to “DH-ify” South Asian studies and more aware of colleagues who share that passion.

In terms of impact on cultural heritage & library sciences, the workshop clearly illustrated how libraries and academic departments can partner to unlock the riches of multilingual archives with AI and ML. By training scholars in these tools, the event contributed to a more inclusive future for AI training data itself: as participants digitize and share their texts, they expand the pool of South Asian language data, helping improve OCR/HTR for those languages down the line. This virtuous cycle – scholars as both users and contributors to digital datasets – was an underlying message of the workshop. Ultimately, the SASDHW demonstrated the power of combining humanistic inquiry with computational methods in a collegial environment. It fostered a new generation of South Asia scholars who are not only consumers of digital tools but conscientious co-creators of epistemic knowledge. In the words of grateful attendees:

“Basically I attended to learn about the state of the art – and was quite surprised ... It [the workshop] surpassed my expectations.”

“Thank you so much for organizing the digital humanities workshop. It was so useful and enlightening for someone like me who was a total novice!”

“Thanks a lot for putting together this workshop. It was useful (I have tried to do all of what we did on day one on my own a couple of times, hit snags, and given up), I enjoyed it, and I learnt several things -- more than I had anticipated. My familiarity with digital tools and my confidence in using them were both significantly augmented. Indeed, this makes me want to go back to years now long past when I used to do some programming, just so I feel more comfortable dealing with and manipulating the materials I use for research on my system, and dealing with my system more generally.”

“I wanted to thank you for the great DH workshop. I really feel like I learned a lot of important skills, and I enjoyed both sessions. I'm writing to you now as I want to continue growing my skills in this realm.”

The success of this event bodes well for more such collaborations in the future, as the community continues to grow and weave together the textual heritage of South Asia with the cutting-edge technologies of the 21st century.

Expanded Learning Outcomes by Session

Here’s a deeper breakdown of what participants learned in each session:

Manuscript Showcase Learning Outcomes:

- Gained material literacy: understanding what features (e.g., ink bleed, column structure, marginalia) hinder OCR accuracy.

- Reflected on the ethics of digitization: who digitizes, what gets digitized, and how those choices shape AI training data.

- Explored how manuscripts can serve as training sets for large language models, adding multilingual diversity.

Keynote Learning Outcomes:

- Learned strategies for preparing and cleaning corpora.

- Understood the limitations of OCR for South Asian scripts – particularly handwritten or historical documents.

- Saw use cases of regex, text mining, and comparative philology using OCRed texts in Sanskrit and Prakrit.

OCR & Technical Workshops Learning Outcomes:

- Installed and configured tools: Google Cloud Vision, Python, BRISS, Sanscript.

- Practiced segmentation and image cleaning before OCR.

- Successfully OCR-ed at least one South Asian language text and learned to debug common errors.

- Learned to transliterate OCR output to Roman script using Python tools.

Multilingual Computational Text Analysis Learning Outcomes:

- Used grep and BBEdit for searching across OCRed corpora.

- Explored entity recognition and pattern discovery using Google Pinpoint.

- Created word frequency visualizations and topic trends in Voyant Tools, even in non-Latin scripts.

The workshop not only gave scholars tools but seeded a new culture of collaborative project development in the South Asian Digital Humanites space. This community now has the momentum to pursue grants, form working groups, and develop shared digital corpora.

Future Workshops requests

Actual demonstration of Dharmamitra application. Any time during year. Rgveda textual analysis (dating) via Dharmamitra

Geo-spatial mapping. Advanced version of this workshop where we go through basics of python and work on troubleshooting.

OCR/HTR with other tools and about different transliteration schemes available through various digital tools

Geo-spatial Mapping for South Asianists

OCR/HTR wit Python Refresh", "OCR/HTR with other tools", "Research Data Management Best Practices"

I would be interested in workshops that focus on the transliteration of South Asian languages into Latin. The concern is that in languages like Malayalam, some letters called "chillakșaram" are not encoded in various transliteration schemes and often have to be undertaken manually. Doing that manually can be very time-consuming.

Geo-spatial mapping. Organizing archives using the different software available.

Photos by Kashi Gomez, Jajwalya Karajgikar, and Penn Libraries Strategic Communication

Note of Acknowledgement: This blog post has been proofread and made accessible with alt-text using tools integrated with Gen AI Tools.