Penn Libraries hosts “Preserving Your Family’s Keepsakes” event at Ginger Arts

On Saturday, November 22nd, Penn Libraries’ Public Digital Humanities Librarian, Cynthia Heider, and Mick Overgard, Head of the Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text and Image (SCETI) hosted a hands-on “Preserving your Family’s Keepsakes” event for members of the Philadelphia community at the Ginger Arts Center.

In partnership with conservators Joelle Wickens and Anisha Gupta from the University of Delaware, this event taught attendees best-practices for safely preserving their historical materials, made experts in digital preservation available to digitize materials into more readily-shared forms, and provided free conservation materials like acid-free archival boxes.

Matt Hunter, Penn Libraries’ Head of Digital Scholarship (MH) sat down with Mick (MO) and Cynthia (CH) recently to discuss the event and how their work continues to intersect with the history of Philadelphia’s community and exemplify the importance of post-custodial archival practices.

MH: How did you come up with the idea for this event?

CH: Well, we've been planning something like this for a while. This type of community work is now one of the explicit initiatives of the Libraries’ Knowledge for Life strategic plan, but since I come from a public history background, I’ve kind of hoped that we would be able to host some events like this for long time. I like the idea of working with the communities around Penn, and in Philadelphia more broadly, since we can provide the equipment and expertise for the community. But Mick, I know you and your team have been thinking about something like this for a while, too.

MO: Yep! I think we started the conversation about something like this event way back in late 2023 or early 2024. Samantha Hill [Curator of Civic Engagement, Kislak Center for Special Collections] had already been in conversation with some groups that may want community digitization as part of other programming, and we did one such event with Samantha in October. But within SCETI we had been talking about how we might be able to do something like this with the broader community for a while. Once we learned that you had a potential use-case for it, it was really great to get moving on something real.

CH: Yeah, definitely. A vital part of getting this event off the ground was interest from a friend and conservator, Anisha Gupta, a PhD candidate from the University of Delaware who’s been working on a dissertation centered on community clinics for object conservation. Having some conversations with her about bringing services that Penn can offer to the public just seemed like a perfect combination of the two areas of expertise. It could make an event like this something a little bit distinct and a little different.

MH: Was this a conservation or digitization event?

CH & MO: Both!

CH: So, we sort of divided the event into two one-hour segments, with the first being a time for folks to talk about the objects that they brought with them. They got to share their stories behind their objects to us a little bit - why it matters to them, whether it was something from their family’s history, why they were concerned about preserving it for the future, things like that. It was also a time to discuss how they’ve been storing it so far and educate them on preservation topics - was it in a shoe box? In the basement? In the refrigerator? Joelle Wickens [Director of the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation] and Anisha have described this time during community events as a sort of “therapy session” for attendees to talk about their materials. It’s also a time where we can give advice about conservation strategies. There’s obviously really expensive conservation solutions, but folks might also be able to at least mitigate damage by doing something safer than keeping it in a shoe box, and we can help share those tips. The second hour was the actual digitization portion, where SCETI helped capture the very high-quality, large images of the objects and hand them back on the flash drives we provided. That way the attendees could take their objects and their digital copies back with them to do whatever they wanted.

MO: Yeah, that was really important to us. We don’t keep the images.

MH: So Penn is just facilitating the process?

MO: Yeah, exactly. And in this case, the bulk of the conservation materials were actually supplied by our University of Delaware partners, not Penn. Not only did we provide a way to have a digital copy, but we offered some solutions for preserving the original materials for the future as well. We gave out things like acid-free boxes and folders for documents, some acetate sleeves for photos, and other things like that.

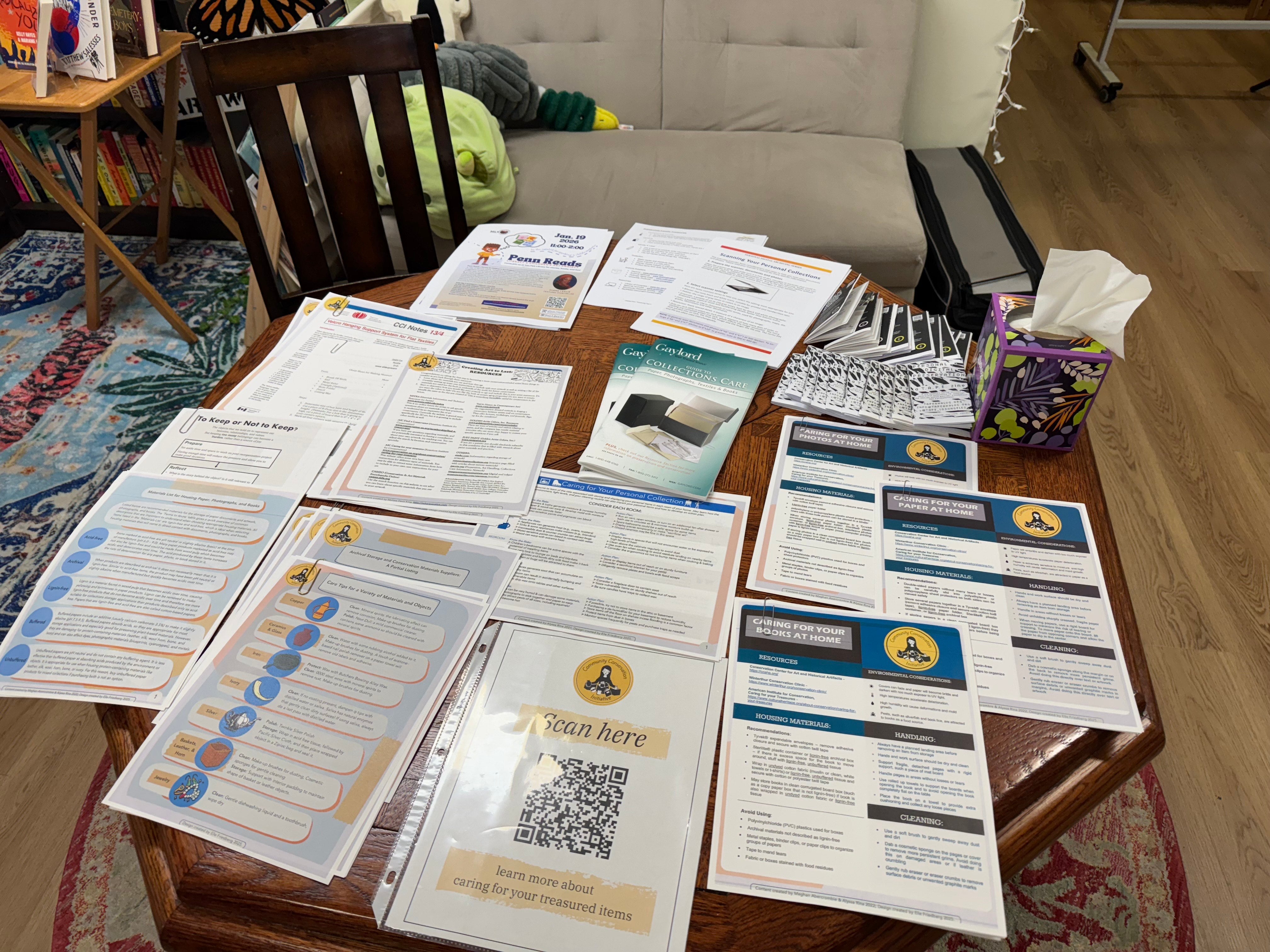

CH: Yeah, and we also brought in some educational materials, like “cheat sheets” essentially, for how to best look after your materials and take better care of them at home to help preserve them into the future. [You can find the materials that our University of Delaware partners provide about conservation, and sign up for their email list, at this link.]

MO: Yeah.

CH: One of the goals of this event was to sort of demonstrate that we can come in (from Penn) and share expertise and leverage the kind of equipment we have to do this type of teaching and digitization, but it’s not about us becoming the owners or stewards of this material. It’s a chance for us to share our knowledge out or give some resources so people can what works best for themselves and their own purposes. Or maybe teach their own friends, relatives, or parents how to better take care of their photos so they can do the same thing. The point isn’t for Penn to come in and host this one-time event where we take in all this material to provide future access to it. Its more so making the knowledge available so that people can learn good practices and keep practicing it in their own lives so that this history and knowledge can be shared in their important community spaces. This is a core concept of post-custodial archiving - we don’t need to take ownership of the materials to help preserve it, and we don’t need to be involved in judging what’s “worth” preserving. That’s up to the communities.

MH: You’ve kind of touched on this a bit already, but what is it that makes this sort of community archiving challenging?

MO: There are a few parts to this, I think. First, there’s the challenge of “you can only prepare for so much” before you go to an event like this. You don’t know how many people will show up or what types of items they’ll bring. We can—and do—provide parameters for suitable materials, but it’s still up to the attendees. So that makes preparing challenging. And sometimes it’s difficult to manage the actual timing of the event, which depends on how many people show up and how much they bring. It worked out great for this particular event since the turnout was manageable, but it’s sometimes a challenge to keep the event moving and make sure it’s possible to get to actually digitizing everyone’s objects. That being said, it’s always great that people want to share so much about the wide variety of materials they bring and it’s great to give them that time at the beginning to share, even if it might make time management a bit tricky. Some of the things that stand out to me the most about events like this are the stories and memories people share about the materials they bring in. Some of it is just very moving. Speaking a bit on behalf of the SCETI photographers [Andrea Nunez & PJ Smalley] who did the imaging this time, photographing a contextless object just feels different than handling a photograph from 1980s Mexico that is the only existing image of someone’s uncle. It makes it very special to know that we get to help preserve that for them in some form.

CH: Yeah. The very fact that people are this excited, and get so involved in talking about these things shows that there’s a strong desire for the time and space for people to be able to talk about why their history matters to them. For why these objects are important to them. They get to show what they care about in this space, and that’s special. We don’t often get to have that kind of space, and I think it’s really rewarding on both sides of the table for people to have this chance to talk about these things and why they matter to them.

MO: Exactly.

CH: I think another thing that’s important about these lower-stakes, community events (and Anisha talks about this in her dissertation) is that they demonstrate that the idea of doing conservation, archiving, or preservation and digitization work doesn’t have to be some inaccessible thing. It’s not true that unless you have this expertise, or have a degree for it, or are part of professional archiving organizations or something, that you can’t do this work. I understand why that might feel true, but the purpose of these events is to underscore that there’s no reason it should feel intimidating to come and do this work. It’s important that these events demonstrate that coming to talk with other community members about why something is important to them and asking questions about how to keep things like photographs safe is accessible to everyone. People shouldn’t need to justify why they want to talk about their family’s history, or have some sort of specialized knowledge to want to do preservation work on their materials. These events are to provide spaces for people to learn these skills and not be snobby about it, and make them more comfortable to enter into these conversations. So that’s a huge challenge to overcome when doing these events, and I think we did a pretty good job this time making sure that was communicated clearly.

MO: Yeah, absolutely. Well put! On a slightly different note, there are a handful of elements on the photography side that makes events like this a challenge. Sometimes it’s hard to know certain things about the spaces we go into like how much light pollution we’ll have to contend with, or, really, how much space we would even have to spread out with our equipment. That was true for this event, but we were able to mitigate it pretty well. Also, going back the need to be flexible, the materials that people bring for preservation are sometimes just hard to prepare for in advance. Even though we provided guidelines for what we can handle, we’re never totally sure if people will bring in highly reflective or shiny things (like photos with silvering, or that are in plastic sheets or frames), and it’s hard to get around the reflections to take a good photograph in certain instances. For this event, luckily, all the objects participants brought were actually pretty easy, but it can be challenging more generally to handle these types of things on the fly.

CY: Especially for this event, I think SCETI did a good job in the moment to explain “this will be hard to image because…” just so people were aware, even before you were able to capture things. I think that helped set expectations well.

MH: So what kinds of materials did you encounter? What was the most common item?

MO: I recall lots of photographs, and I think there might have been more than one zine. That was really cool! I think somebody made it for some college work and brought it in. There were also a number of materials from around Ginger Arts [the host venue] itself that were digitized as well. Things like art or other materials that had been hanging on the walls, things like that.

CH: There was also a bracelet that someone brought it, so it wasn’t all photographs or documents. We shared guidelines for the event that stated that materials needed to be less than 13” x 18” and that could be imaged flat, so 2D things were the most common. At a previous event, I know there were some other, bigger, cool things like cookbooks. Someone even brought a kimono once, which was wild! But we didn’t have that this due in part to those guidelines.

MH: So the purpose of the digital capture was just to create a usable 2D image of the object, rather than a true digital copy, like a 3D model?

MO: Yeah, for this event we brought a copy stand and a flat paper background to make sure we could grab good images of flat things. The camera is situated directly above the objects, and we can capture a good image of the object, but we weren’t necessarily able to capture the dimensionality of things like a bracelet.

MH: So what kinds of things can these digitized materials be used for now?

MO: There was a ton of talk at the event about sharing the images with family members now that these things have been digitized. So much of the material was relevant to folks’ family history. I think the person who created the zine also wanted to share it more widely, but I don’t know if they had a particular audience in mind yet. But that’s the benefit of them being digital files now. As part of the event we also provided a lot of informational material about what to do to preserve the digital files now, which I hope is useful. The point of the event was obviously to help preserve access to the physical materials, but it’s also now important to make sure that the digital files are safe. So we included recommendations on things like how to best store, save, and share the materials safely.

CH: Yeah. There’s kind of an infinite number of things people could do with these images now, but the event was mostly focused on how we can help with conservation of the materials and preserving a digital copy of them. We’re happy to let people’s imaginations run wild about how to share or use them further.

MH: So what’s next for these community-engaged events?

CH: Well, I’m in the process of discussing a similar event with the community group Taller Puertorriqueño during the Spring 2026 semester, so keep an eye out for more details on that soon. And I’d love to do more of these styles of events for more community partners beyond that, generally. I’d love to keep working with our conservation partners at the University of Delaware too. I’ve also been thinking about digital preservation more widely after this event. It would be great to foster more of a space within the community for members to start thinking about how they themselves are history-makers. That it’s not just the physical materials of their parents or grandparents they’re digitizing that are worth saving, but also the content they’re generating for social media that will be the historical landscape of their own lives and experiences for future generations. But that’s a little bit more complicated to think through in terms of things like copyright, privacy, and things like that. So thinking about how to teach during an event like that is still a bit down the road.

MO: In addition to that, SCETI has been thinking about how to do more instruction about photography and digitization skills to broader audiences more generally. I think we’re looking to focus on how to teach people to digitize their own materials—whether that’s through their phone camera or a DSLR, even. It’d be great to have those sessions to be focused on community partners, too.

CH: Yeah. All of this work is sort of in an effort to lower the barrier of entry for how community history and “digital preservation” concepts can be for everyone. Photos don’t have to be a crazy high-resolution TIFF file to be useful for sharing and preserving materials. And there isn’t some minimum criteria for something to be preservation-worthy for your family’s history, or your records, you know?

MH: These all sound like great ideas. Is there anything else you’d like to share about upcoming work?

CY: Only that we’re always looking for more community partners to do this type of event! So if you’re in the community and interested in playing around with digitization, conservation, or even just community history, please do reach out! You can reach me at heider@upenn.edu.

MO: Yes! It would be really cool to continue doing these types of events.